James Wrigley – my great great great grandfather – therein lies a tale.

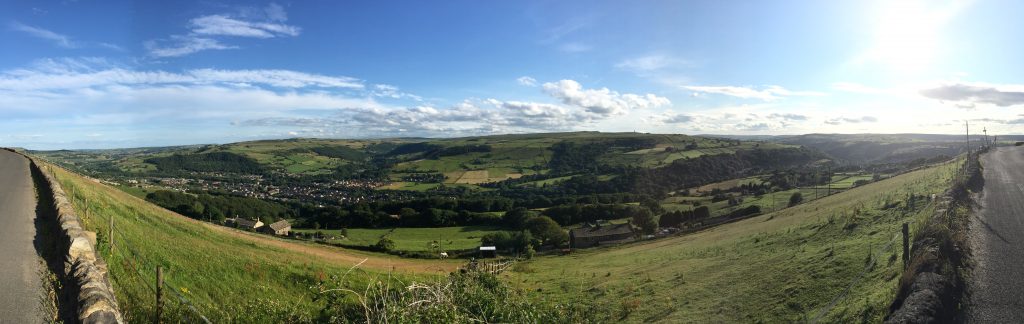

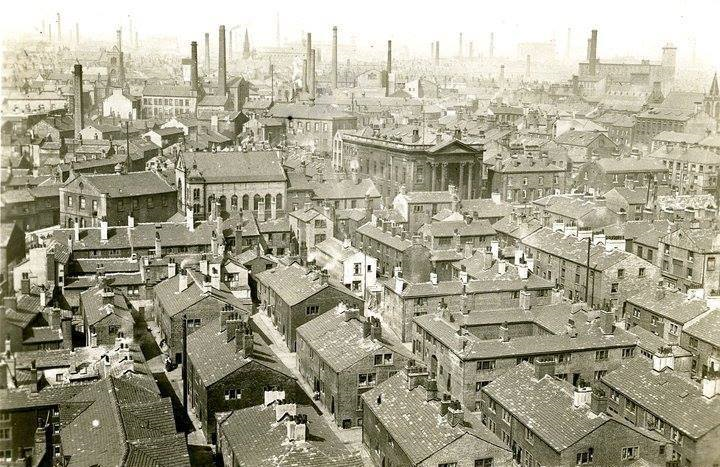

Between 1809 and 1811 James and Mally Wrigley moved from their home on Toad Lane Rochdale to Heptonstall. Toad Lane Rochdale is famous all over the world for being the home of the Cooperative movement. In fact, I went to a lecture last night given by the Hebden Bridge Local History Society about the origins of the first cooperative mill, Nutclough Mill which just happens to be in in Hebden Bridge, and how it was eventually bought out by the Cooperative Wholesale Society. It brought back memories for me of going to the Coop in Bolton, not just for food, but I had my elocution lessons in a room upstairs, was a member of the verse speaking choir (which is why I can recite so many poems) and the singing choir. Verse speaking and elocution festivals were held in the ballroom about the food store. I also went to the Coop dentist and Coop opticians in that building. The first coop on Toad Lane Rochdale is now a museum which I visited during my summer trip to England last year. The site of the museum at 31 Toad Lane was where the ‘Pioneers’, 28 working people opened a co-operative store on the 21st December, 1844.

I’d discovered, surprisingly, that James and Mally Wrigley are my great great great great grandparents. It’s from my connection with them that I am related to the Wrigley builders of Hebden Bridge, and the Gibsons of Hebden Bridge. Between the birth of their fourth and fifth sons the growing Wrigley family moved from Rochdale to Heptonstall. I don’t know where they lived immediately but by 1840 they were living in Lily Hall. Lily Hall is pivotal in my family history.

Lily Hall, Heptonstall

But for the Wrigleys of Lily Hall I wouldn’t have the ancestors in Heptonstall and Hebden Bridge that first brought me to stay in this area with Rachel in the summer of 2015 which eventually led to me moving to Hebden Bridge in Sept 2017 after 32 years in the U.S.

When James (junior) was married at St Thomas’s, Heptonstall on March 15, 1840 he was living with his parents James and Mally in Lily Hall. His occupation is given as a white limer, one who paints walls and fences with white lime, and his father is a cabinet maker. James’s new bride is Mary Pickles of Rochdale. James and Mary both made their mark in lieu of signature so they were probably illiterate. A witness to their marriage is Thomas Gibson, a 20 year old whitesmith who was living next door at Lily Hall. Sometime the following year in 1841 Mary gave birth to a son, Thomas, who soon died and was buried at St Thomas’s on July 15, 1841. In 1843 Sarah was born and a year later Martha in 1844. In 1847 Mally was born – named after her grandma. By the census in 1851 James and Mary were living at Town Gate Heptonstall and James is a head plasterer, thus carrying on the family tradition of being connected with the building trade. In 1852 James’s wife Mary died at the age of 37. She’s buried at St Thomas’s: Plot #V1 9 Flat In memory of MARY the wife of JAMES WRIGLEY of this Town who died June 12th 1852 aged 37 years Also of JAMES WRIGLEY her husband who died Sept 2nd 1886 aged 75 years. Two years, 2nd July 1854 later he married another Mary, Mary Ackroyd, a widow whose maiden name had been Pickup. The following month (!) their daughter Mary Ann was born on August 21st. The next 3 censuses 1861, 1871, 1881 have the family living at Millwood, an area between Hebden Bridge and Todmorden near the Shannon and Chesapeake pub (which I noticed yesterday is closed and up for sale for £195,000). Mary died in 1876 and James lived to the grand old age of 75 and was buried with his first wife (!) at St Thomas’s.

Shannon and Chesapeake pub is for sale

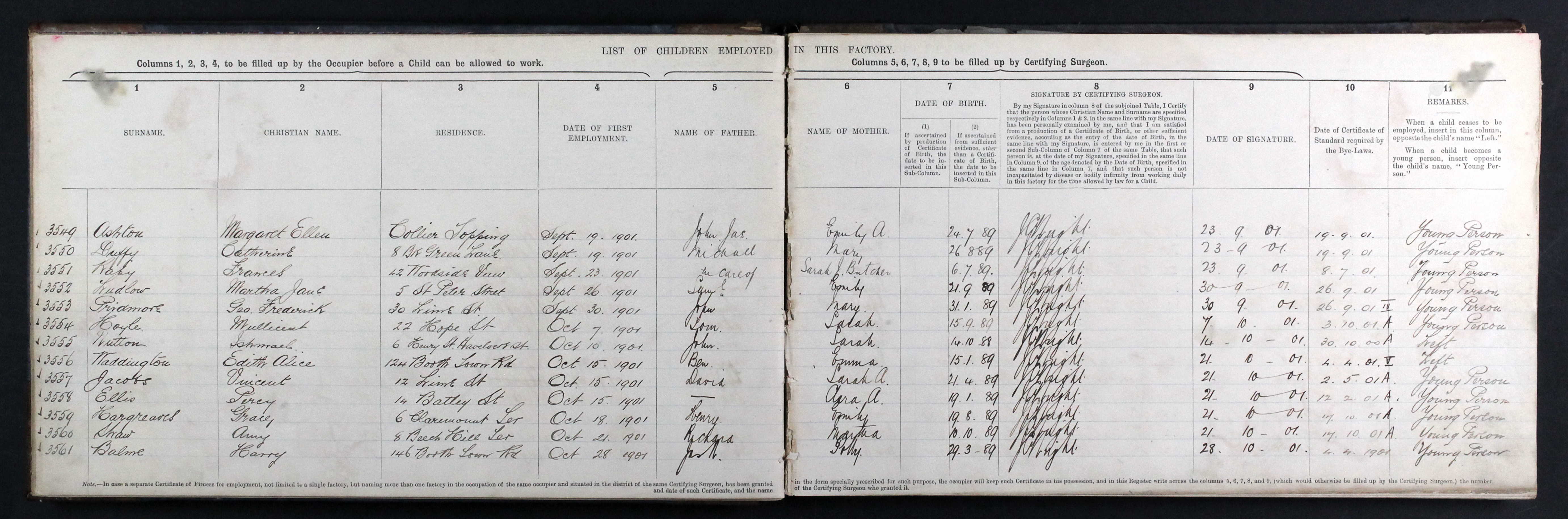

So, how does all this tie in with MY family tree. Well, here’s an article I wrote explaining just that. It was published in the Calderdale Family History Journal:

Elizabeth Ann Whitham

In the summer of 2016 I spent seven weeks in Calderdale researching my maternal grandmother’s ancestry. Though born and raised in the tiny village of Affetside in Lancashire I now live in Northern California and I was eager to make this trip to find out more about my heritage. For the previous seven years I had been doing as much research online as possible but I had come upon a puzzling fact: my great, great grandmother, Elizabeth Ann Whitham had been married twice, but had given the name of two different fathers on her two marriage certificates. First Elizabeth Ann married Ishmael Nutton at St John the Baptist church in Halifax on April 27, 1861. His residence at the time of marriage was Skircoat and Ishmael’s occupation was woolsorter. Ishmael’s father, James Nutton gives his occupation on the marriage certificate as woolsorter too. Elizabeth Ann, whose residence was Halifax, gives her father’s name as William Whitham with the space for his occupation left empty. In the 1861 census an Elizabeth Ann Whittam (born Heptonstall, 1841) is a cook at a large boarding school on Hopwood Lane, Park House. So far, so good. The school was run by the Farrar family. John Farrar (1813-1883) born at Heptonstall (just like Elizabeth Ann) was the “schoolmaster: Classical, commercial and mathematical.”(1861 census). Interestingly the road that joins Shaw Hill in Skircoat is Farrar Mill Road.

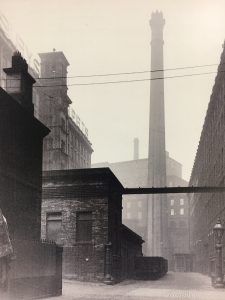

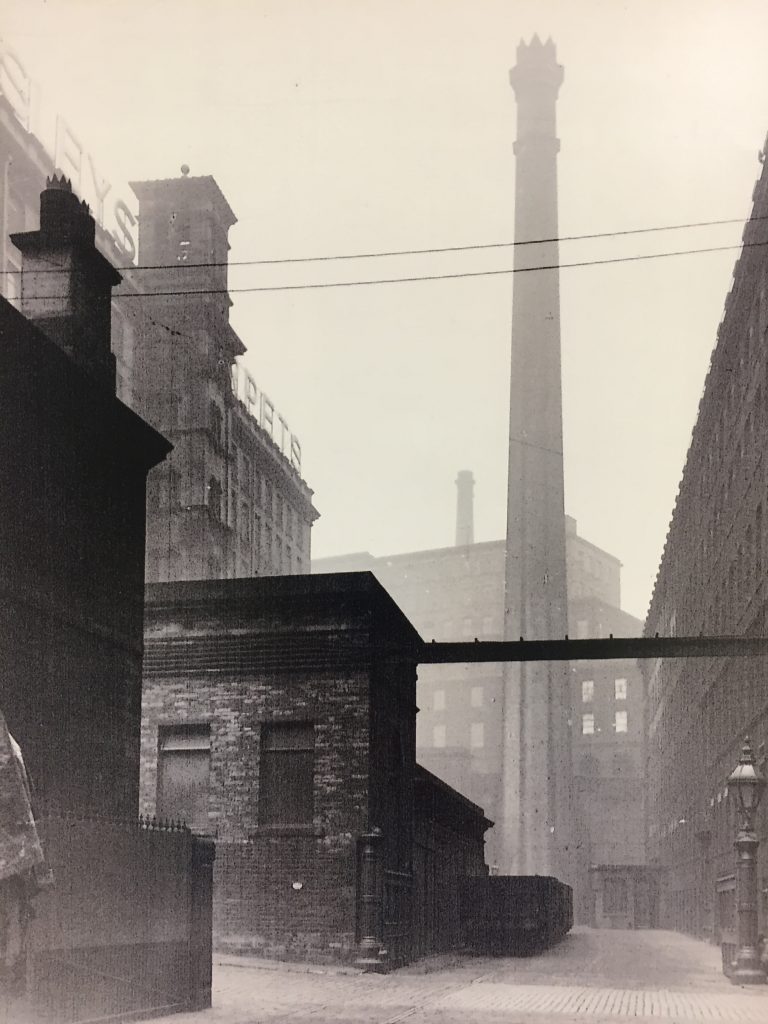

Ishmael died from alpaca poisoning (sorting alpaca wool) on March 17 1876. I found his grave at Christ Church Mt Pellon. Elizabeth Ann, now 40,  was now head of the household living at 20 Haigh Street, Halifax, with her sons Charles 18, John 17 and William 14. She also has a lodger, James Hainsworth Leeming, eleven years younger than her. In 2016 I went to find her house. Haigh Street is still there, partially, but as ill-luck would have it the part I wanted has been demolished. It’s a street sandwiched between factory buildings, many of them derelict. Five years later Elizabeth Ann married James Leeming, a widower, originally from Horton near Bradford. But here, things get a little more complicated because she gives the name of her father not as William Whitham but as James Wrigley, a plasterer. Try as I might I just couldn’t figure this out. She’d given two different names for fathers on her two marriages. The simplest explanation is that I’d got the ‘wrong’ Elizabeth Ann, but that didn’t seem likely since the birth years were about the same and they’d both been born in Heptonstall. Completely at a loss I just happened to find a person online offering to help with people’s ancestral brick walls in Calderdale. I emailed Roger Beasley of the CFHS one evening in August, giving details of my predicament and, lo and behold by the time I woke up the next morning he had solved my mystery. He wrote: “I think I may have worked out why Elizabeth Ann Whittham gave both William Whittham and James Wrigley as her father. Her mother, Sally Farrar, daughter of James Farrar, married William Whittham in 1822. Their children were: Hannah (b.1828), Farrar (b.1831), John (b.1833), James Farrar (b.1837). William Whittham died in 1837. In the 1841 census there was a James Rigley, plasterer, living next door to the widow, Sally. It seems possible that Elizabeth Ann Whittham was the illegitimate daughter of Sally Whittham and James (W)rigley. I couldn’t find a baptism for Elizabeth Ann Whittham which was common for children born out of wedlock. However, I did find the record of her birth in 1840 on FreeBMD.” Perhaps Elizabeth Ann herself wasn’t aware of her true father when she married for the first time. But Roger Beasley’s email also contained two other very important facts. I’d been unable to trace Elizabeth Ann’s mother. Roger found her to be Sally Farrar of Heptonstall. When I got the church records for St Thomas’s Heptonstall there are 190 Farrar baptisms recorded! Roger did find a birth record of Elizabeth Ann in 1840 on FreeBMD in which she’s registered in Todmorden. When her birth certificate arrived from England I found that, sure enough, as Roger had surmised there is no father named on it. Her mother’s name is Sally Whitham nee Farrar and Elizabeth Ann was born at Lily Hall. I can’t help wondering if James Wrigley and his wife knew that Sally was giving birth to James’s daughter literally in the next room – in Lily Hall.

was now head of the household living at 20 Haigh Street, Halifax, with her sons Charles 18, John 17 and William 14. She also has a lodger, James Hainsworth Leeming, eleven years younger than her. In 2016 I went to find her house. Haigh Street is still there, partially, but as ill-luck would have it the part I wanted has been demolished. It’s a street sandwiched between factory buildings, many of them derelict. Five years later Elizabeth Ann married James Leeming, a widower, originally from Horton near Bradford. But here, things get a little more complicated because she gives the name of her father not as William Whitham but as James Wrigley, a plasterer. Try as I might I just couldn’t figure this out. She’d given two different names for fathers on her two marriages. The simplest explanation is that I’d got the ‘wrong’ Elizabeth Ann, but that didn’t seem likely since the birth years were about the same and they’d both been born in Heptonstall. Completely at a loss I just happened to find a person online offering to help with people’s ancestral brick walls in Calderdale. I emailed Roger Beasley of the CFHS one evening in August, giving details of my predicament and, lo and behold by the time I woke up the next morning he had solved my mystery. He wrote: “I think I may have worked out why Elizabeth Ann Whittham gave both William Whittham and James Wrigley as her father. Her mother, Sally Farrar, daughter of James Farrar, married William Whittham in 1822. Their children were: Hannah (b.1828), Farrar (b.1831), John (b.1833), James Farrar (b.1837). William Whittham died in 1837. In the 1841 census there was a James Rigley, plasterer, living next door to the widow, Sally. It seems possible that Elizabeth Ann Whittham was the illegitimate daughter of Sally Whittham and James (W)rigley. I couldn’t find a baptism for Elizabeth Ann Whittham which was common for children born out of wedlock. However, I did find the record of her birth in 1840 on FreeBMD.” Perhaps Elizabeth Ann herself wasn’t aware of her true father when she married for the first time. But Roger Beasley’s email also contained two other very important facts. I’d been unable to trace Elizabeth Ann’s mother. Roger found her to be Sally Farrar of Heptonstall. When I got the church records for St Thomas’s Heptonstall there are 190 Farrar baptisms recorded! Roger did find a birth record of Elizabeth Ann in 1840 on FreeBMD in which she’s registered in Todmorden. When her birth certificate arrived from England I found that, sure enough, as Roger had surmised there is no father named on it. Her mother’s name is Sally Whitham nee Farrar and Elizabeth Ann was born at Lily Hall. I can’t help wondering if James Wrigley and his wife knew that Sally was giving birth to James’s daughter literally in the next room – in Lily Hall.

Lily Hall

So in September 2016 I embarked upon some research into the family of James Wrigley. After all, if these facts are correct he is my great, great, great grandfather! I found two online Wrigley family trees with the correct James Wrigley, of Heptonstall. I contacted both tree owners and they both live in New Zealand. James was one of eight children. One of his brothers was Abraham and remarkably there was a photo of Abraham taken with his own son John. From Grace Hanley in New Zealand I found out that “John came to NZ in 1863, Edmund in 1865 and Hannah, James and their mother Sally arrived in NZ, 1883.” James Wrigley, Elizabeth Ann’s biological father had married Mary Pickles on March 15th 1840. One of James and Mary’s children was Mally Wrigley. She married James Barker of Water Barn, Rossendale on July 14, 1866 in Heptonstall. Mally and James were both weavers when they married but by 1871 and 1881 he was a cotton operative.

I will return to Calderdale this summer to further my research and would love to meet up with people who may have recognized some of their ancestors in my story.

With many thanks to Roger Beasley.

So, just two months after James married his first wife Mary Pickles, his next door neighbor gave birth to James’s child, Elizabeth, who took as her surname her mother’s married name of Whitham. On June 11th 1840 just 3 weeks after Elizabeth Ann was born at a petty sessions held at the White Hart in Todmorden in front of 2 justices of the peace James was acknowledged as Elizabeth Ann’s father and ordered to pay 4s 6p to the Overseers of the Poor in Heptonstall for the maintenance and support so far incurred and he is ordered to pay weekly 1s 6p weekly until the child reaches 7 years of age. When Sarah and I had lunch in the White Hart we’d no idea of how significant a role this building had been in our family’s history.

Through a couple more years of research, especially when I moved to Hebden Bridge I found out more about the Wrigley family. They continued to expand their building business, building some of the largest buildings in Hebden Bridge and surrounding area. But that’s for another post on my blog. Sally had already given birth to six children when she had Elizabeth. Their early deaths make very sad reading. Her first two children died less than a year old. Her third, Hannah, outlived her, dying at 66, then Farrar died aged 5 and John aged 2, then she had James Farrar (1837-1901) and 7 months later her husband, William Whitham died. No wonder she was living back with her parents in Lily Hall in 1840.

After my cappuccino and cake I wandered around the galleries for a while and my eye was taken by a new exhibit. Well, that’s a mild way of putting it. I was stunned by it. The subject was wreaths, which, in my books, didn’t sound too interesting, but these celebrated the living, the dead, the lost. One included display included objects that mothers attached to babies they left on charity doorsteps. Another was a wreath wrapped around a hanged man. The one that took my attention was one about a fallen soldier, including family photos, and old pennies to close his eyes. The kit box supporting him listed the number of people killed and wounded in WWl.

After my cappuccino and cake I wandered around the galleries for a while and my eye was taken by a new exhibit. Well, that’s a mild way of putting it. I was stunned by it. The subject was wreaths, which, in my books, didn’t sound too interesting, but these celebrated the living, the dead, the lost. One included display included objects that mothers attached to babies they left on charity doorsteps. Another was a wreath wrapped around a hanged man. The one that took my attention was one about a fallen soldier, including family photos, and old pennies to close his eyes. The kit box supporting him listed the number of people killed and wounded in WWl.

around doing the ‘listing’ and the doors to this chapel were locked that day. It looks austere and dull from the outside so he didn’t list it. Thank goodness! If we’d have been Grade 1 or Grade 2 listed we wouldn’t have been able to do all the things we have done – like build the extension on the back.” As we chatted a man came in to collect some posters and as Dot explained why I was there he invited me to a special celebration of the people of Blackshaw who returned from fighting in WWl but then had to deal with ‘a living hell’ for the rest of their lives. He introduced himself as Tim, and he also told me about A Beacon of Light that’s going to be lit on Great Rock above Eastwood featuring a handbell choir on the evening of Armistice Day. “I’ll see if I can arrange transport, if you need it” he offered. When he’d gone Dot explained that ‘Tim’ is none other than Mr Timothy James Pitt, Vice Lord Lieutenant, one time High Sheriff of West Yorkshire whose interests include ‘country pursuits, classic cars, gardening, golf, breeding Alpacas.’ http://www.westyorkshirelieutenancy.org.uk/vice-lord-lieutenant/

around doing the ‘listing’ and the doors to this chapel were locked that day. It looks austere and dull from the outside so he didn’t list it. Thank goodness! If we’d have been Grade 1 or Grade 2 listed we wouldn’t have been able to do all the things we have done – like build the extension on the back.” As we chatted a man came in to collect some posters and as Dot explained why I was there he invited me to a special celebration of the people of Blackshaw who returned from fighting in WWl but then had to deal with ‘a living hell’ for the rest of their lives. He introduced himself as Tim, and he also told me about A Beacon of Light that’s going to be lit on Great Rock above Eastwood featuring a handbell choir on the evening of Armistice Day. “I’ll see if I can arrange transport, if you need it” he offered. When he’d gone Dot explained that ‘Tim’ is none other than Mr Timothy James Pitt, Vice Lord Lieutenant, one time High Sheriff of West Yorkshire whose interests include ‘country pursuits, classic cars, gardening, golf, breeding Alpacas.’ http://www.westyorkshirelieutenancy.org.uk/vice-lord-lieutenant/

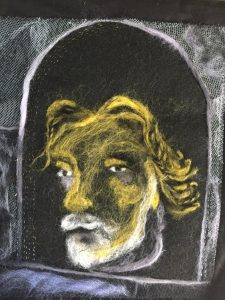

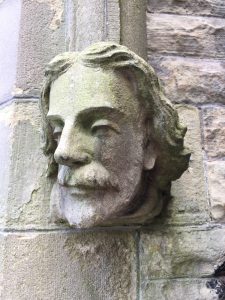

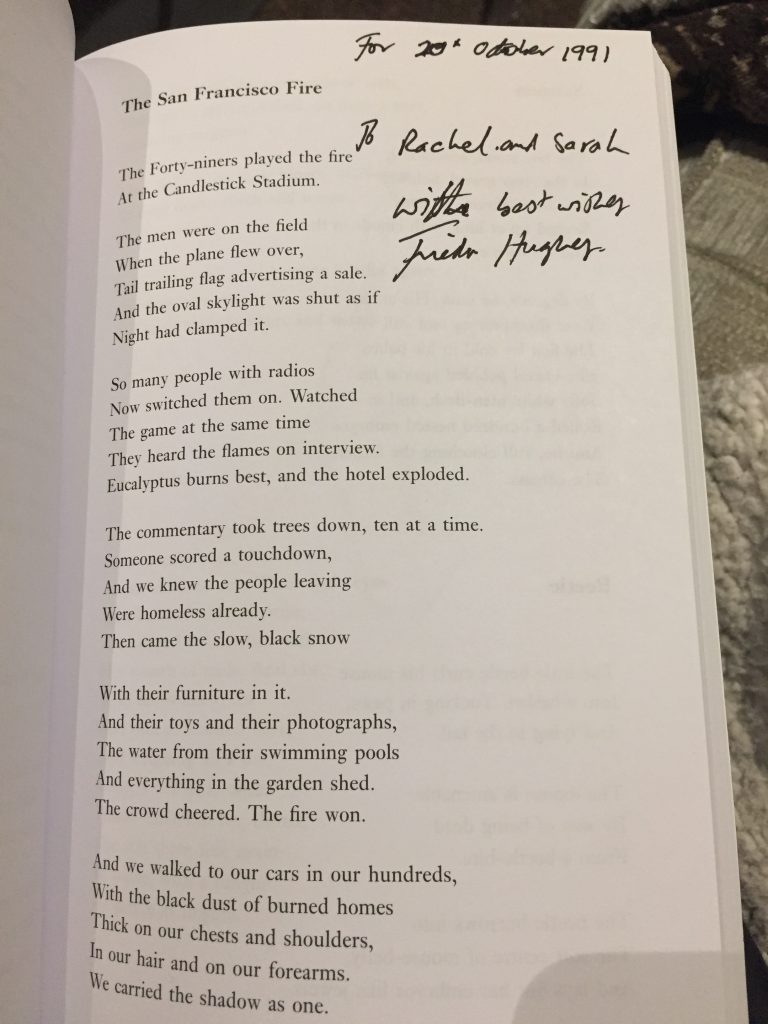

I found it rather uncanny to hear a recording of Hughes himself reading a poem about the room we were sitting in. We were able to see the view from his room of Scout Rock, and see the site of Zion chapel which dominated the street, cutting out all light from Ted’s window.

I found it rather uncanny to hear a recording of Hughes himself reading a poem about the room we were sitting in. We were able to see the view from his room of Scout Rock, and see the site of Zion chapel which dominated the street, cutting out all light from Ted’s window.

thought, a man after my own heart. We chatted happily in this remote spot. It was rather surreal. He organises weekend youth hostelling trips for the over 50’s and had just led a trip that included 3 nights at Haworth YH and three nights in Mankinholes YH. He’d led a walk up to Stoodley pike and the mist had been down and until they were within a couple of yards of the tower they couldn’t see it. Then the sun came out and they had perfect visibility for the rest of the day. Yes, I have ancestors buried at Mankinholes, and when my mum used to tell me tales of her youth hostelling days the strange name of Mankinholes always stuck with me. I’ll look into finding out more about the group. The next weekend is at Hathersage Youth Hostel.

thought, a man after my own heart. We chatted happily in this remote spot. It was rather surreal. He organises weekend youth hostelling trips for the over 50’s and had just led a trip that included 3 nights at Haworth YH and three nights in Mankinholes YH. He’d led a walk up to Stoodley pike and the mist had been down and until they were within a couple of yards of the tower they couldn’t see it. Then the sun came out and they had perfect visibility for the rest of the day. Yes, I have ancestors buried at Mankinholes, and when my mum used to tell me tales of her youth hostelling days the strange name of Mankinholes always stuck with me. I’ll look into finding out more about the group. The next weekend is at Hathersage Youth Hostel.

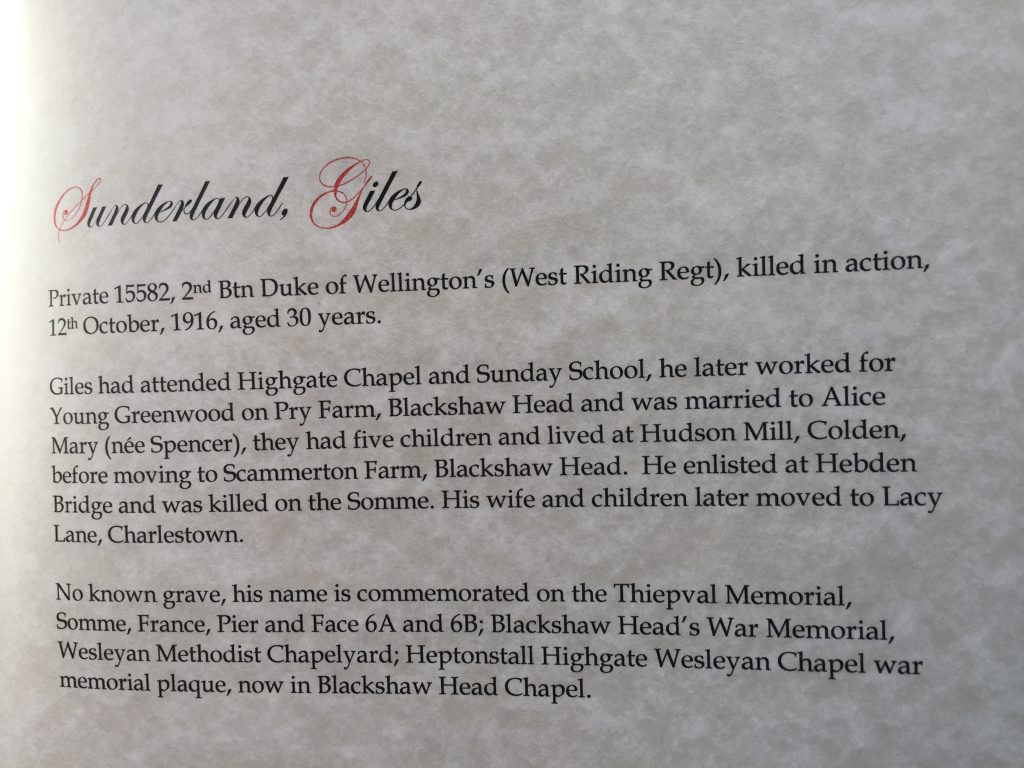

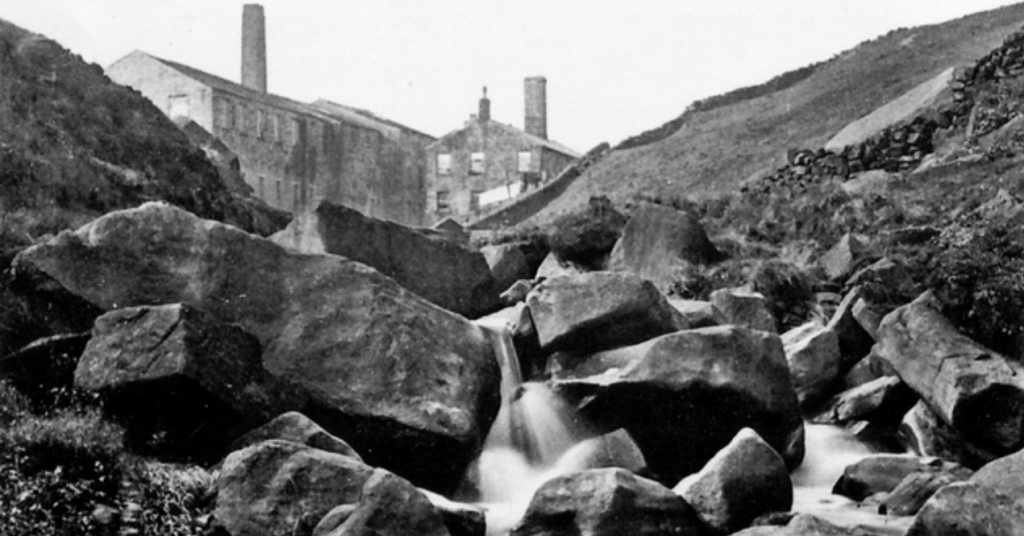

Giles Sunderland (uncle of wife of my 3rd cousin 2x removed) and his family were living in a house at Hudson Mill in 1910. So yesterday I set off to discover it. I got the Blackshaw Head bus to Jack Bridge on a lovely sunny Autumn morning, I’d passed through this little hamlet several times before, both on the bus and in the car when my daughters had visited, and in fact, I’d walked up the Colden Valley to the bridge in 2016, little guessing that I would one day be able to walk to this beautiful spot from my living room! The bridge itself is very narrow. the bus only just fits over it. There are steep, well worn steps to one side and a cat was happily sitting and lazily drinking from various puddles.

Giles Sunderland (uncle of wife of my 3rd cousin 2x removed) and his family were living in a house at Hudson Mill in 1910. So yesterday I set off to discover it. I got the Blackshaw Head bus to Jack Bridge on a lovely sunny Autumn morning, I’d passed through this little hamlet several times before, both on the bus and in the car when my daughters had visited, and in fact, I’d walked up the Colden Valley to the bridge in 2016, little guessing that I would one day be able to walk to this beautiful spot from my living room! The bridge itself is very narrow. the bus only just fits over it. There are steep, well worn steps to one side and a cat was happily sitting and lazily drinking from various puddles.

Access to the top storey was once by a very elaborate pathway wide enough to drive a horse drawn cart along, and it led directly to the stable/barn. This path necessitated the building of a high retaining wall with two elaborate vaulted archway, now used for storage. As we chatted further about our ancestry we joked that we might be related. I discovered that the lady’s husband was a Cockroft and that rang a bell. Cockroft is a very common name in this area. There are hundreds of them in church records. Then it dawned on me the context I’d heard Cockroft: a Cockroft had designed the trestle bridge at Blacke Dean. “Ah, that was my husband’s great great grandfather,” she said. “He was on the first train that went over the trestle bridge when it was completed.” When I visited the trestle bridge footings about a month ago I had borrowed a book from the library and copied a photo of the people on the first train across! And here I was doing research into my own family and finding myself chatting to Cockcroft’s great great grandson’s wife! Small world. It’s this feeling of connection that I sorely missed living in the US.

Access to the top storey was once by a very elaborate pathway wide enough to drive a horse drawn cart along, and it led directly to the stable/barn. This path necessitated the building of a high retaining wall with two elaborate vaulted archway, now used for storage. As we chatted further about our ancestry we joked that we might be related. I discovered that the lady’s husband was a Cockroft and that rang a bell. Cockroft is a very common name in this area. There are hundreds of them in church records. Then it dawned on me the context I’d heard Cockroft: a Cockroft had designed the trestle bridge at Blacke Dean. “Ah, that was my husband’s great great grandfather,” she said. “He was on the first train that went over the trestle bridge when it was completed.” When I visited the trestle bridge footings about a month ago I had borrowed a book from the library and copied a photo of the people on the first train across! And here I was doing research into my own family and finding myself chatting to Cockcroft’s great great grandson’s wife! Small world. It’s this feeling of connection that I sorely missed living in the US.

Recent Comments