What goes around comes around – from Lily Hall to New Zealand and back!

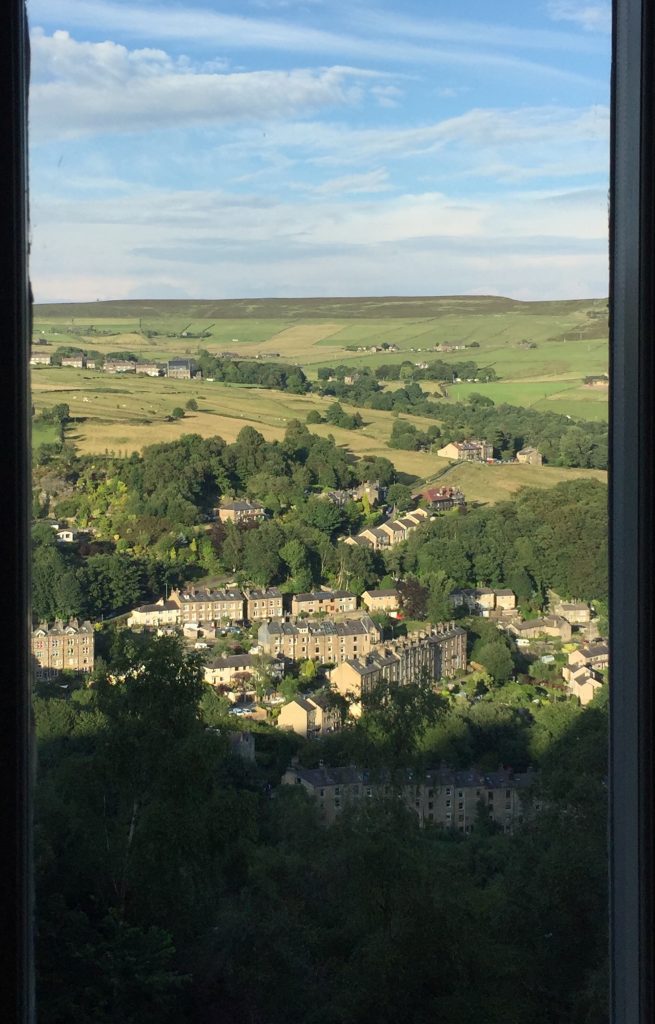

I began my day looking up at the Heptonstall hillside above Hebden Water. Lily Hall’s eyes were firmly fixed on me. I could feel them asking me a question, Well, what about Sally? I needed to find an answer and until I did so I wouldn’t be able to rest.

My 4th gt grandfather James Wrigley,1778-1846, lived in Lily Hall and his son, Abraham was living there when, in 1837 he married Sally Nicholson, a straw bonnet maker, also living in Heptonstall. Both signed their name on their marriage certificate very clearly and with apparent ease which was somewhat unusual for this time period. In the mid 1800s straw bonnets were fashionable for both men and women and plaiting was the process of braiding several strips of softened wheat straw into lengths up to twenty yards. During the boom years the earnings of a wife and her children from straw plaiting could equal the husband’s income from farm labouring. The only requirements were a supply of treated wheat straw, a straw splitting tool and nimble fingers. The straw was cut into 10 inch lengths, fumigated and bleached using sulphur fumes, known to irritate the nose, eyes, throat, and lungs. The next step was feeding each length of straw through an opening in the straw splitting tool to produce thin strips of straw that could then be easily worked into the lengths of finished plait. Plaiting was not without its hazards. To improve the suppleness of the bleached straw, each length of straw was softened with saliva by running through the plaiter’s mouth. This led to sore lips, abrasions and mouth ulcers.

So there sits Sally making her bonnets while Abraham carries out his weaving. The view of the rolling hills from this elevated spot have not changed since their time. Did they admire the view over the valley or is their work so labourious that they have little time to appreciate it, especially with a growing family.

Over the course of the next twenty years they went on to have nine children. I have a lovely formal photograph of Sally, taken in a photographic studio wearing a dress with bishop sleeves, full, long sleeves gathered into cuffs at the wrists.

The shape of her dress would have required a long-fronted, bust-flattening corset which was popular until the mid 1850s and the full skirt is pleated and must have required a lot of material to fall around the hoop. Perhaps she’s wearing a crinoline petticoat stiffened with horse hair, also in vogue at that time.

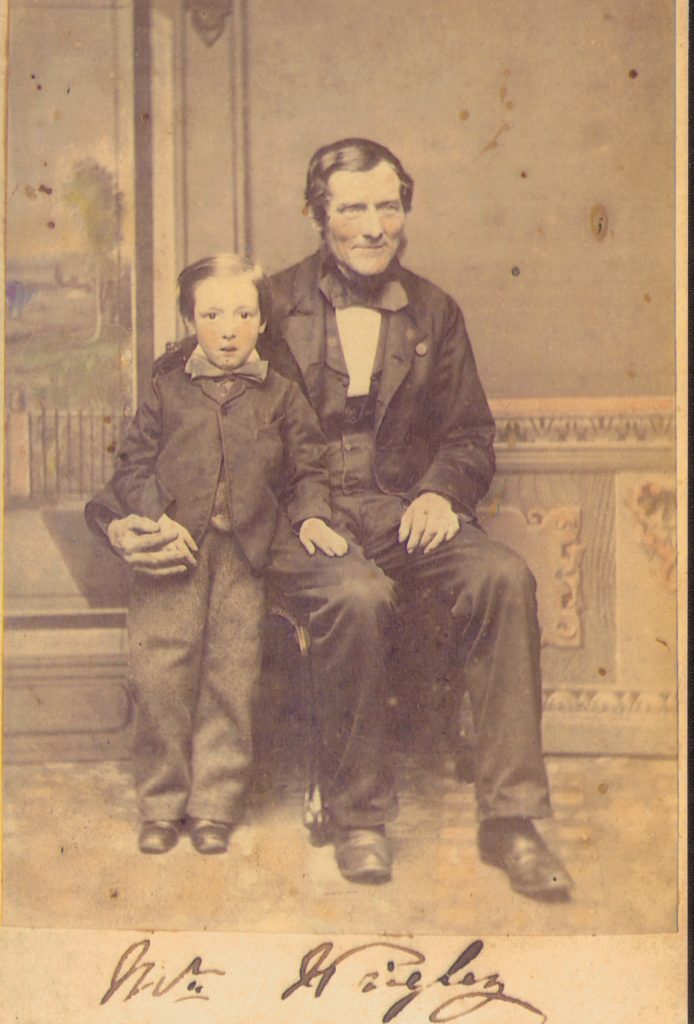

I have a photo of Abraham with his arm around a little boy’s shoulders and clasping his hand. His son looks to be about 7 years old. Unusually for the time period Abraham is smiling in the photograph. This, and the way he’s clasping his son’s hand is very endearing.

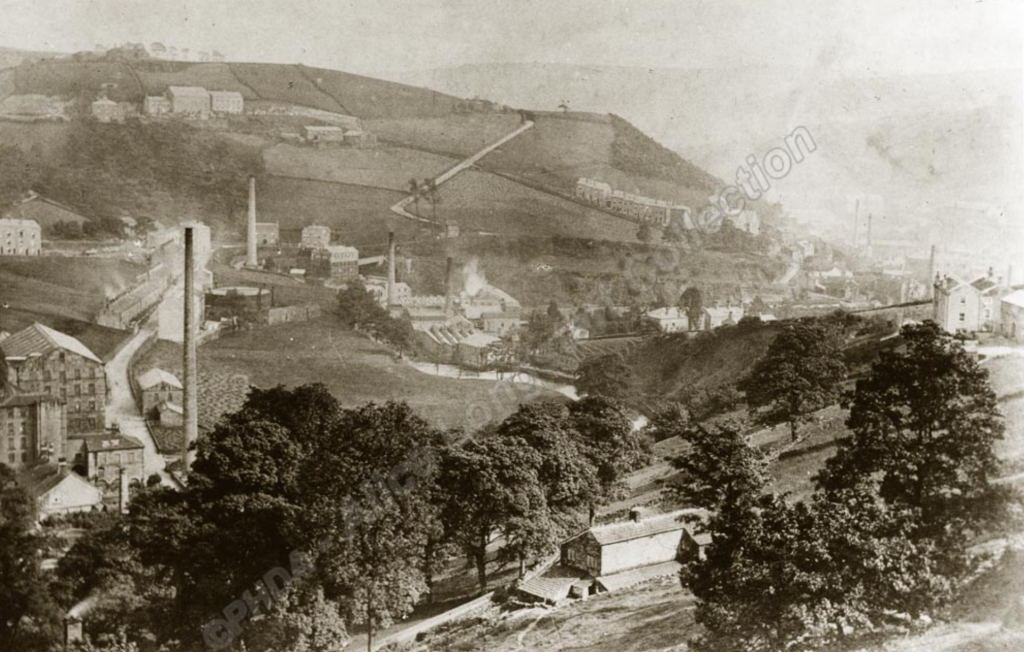

Like the photo of Sally it has been taken in a photographic studio complete with what appears to be a painted backdrop of classical columns and a framed painting of a landscape. It must have been taken for a very special occasion. For a little while Abraham kept a grocer’s shop on the high street in Heptonstall. Today the only shop in the village is the Post Office which sells a small selection of food items for which the village residents have been highly appreciative during the pandemic, though it was closed for a time when the shopkeeper tested positive for Covid19. When it reopened during lockdown I counted more than a dozen people standing in line outside the shop, socially distanced but in danger of getting too close to traffic, especially the wide delivery lorries. Following the death of two infant children the Wrigley family moved to Bury, close to where I was born and grew up but by 1849 they were back in the Pennines, this time taking up residence in Todmorden where another son died in his first year of life. Abraham had become a carpenter working for John Nicholson, Sally’s dad. After their move to Todmorden three more children were born , the last being born when Sally was 41, a veritable geriatric mother. By this time Abraham had become a master joiner and cabinet maker, employing a dozen boys. John Nicholson, Sally’s father, had a house and shop on Cross Street next to Myrtle Street in 1860 and Sally and Abraham were living just a few doors away also on Myrtle Street. By 1861 Sally’s father was calling himself an architect.

I got off the bus in the centre of Todmorden and crossed the Halifax Road heading towards the market. Right now the indoor market is closed but there a few stalls open on the outdoor market, reminding me of the first time I visited – with Rachel in 2015. When I moved back to England I wrote a funny monologue about a visit to this market in the pouring rain and was invited to perform it at Todmorden Literary festival in 2019 held in the imposing brick edifice of the Todmorden Hippodrome. Today the only things left to recall where Abraham and Sally lived are the street signs, Myrtle and Cross which now form access roads into Bramsche Square comprising a small garden and car park.

Abraham died in 1879 and is buried at Lumbutts Methodist chapel. This interestingly named place is a mere hop and skip from the even more astonishingly named Mankinholes. The word has Celtic origins and means ‘fierce wild man, while Lumb means pool and butts means land in Old English. Both villages lie on the shelf of land half way between the bottom of the valley and the hill tops, providing flatter land for pasture and grazing, not to mention flatter land on which to erect buildings.

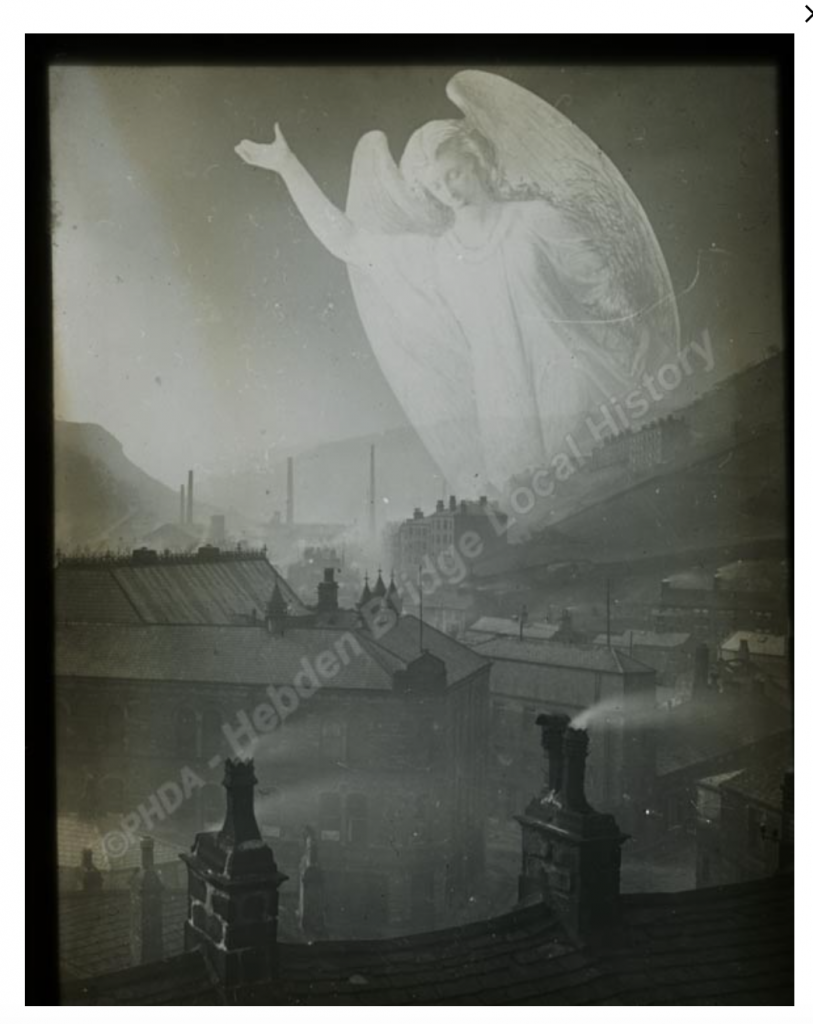

There is a long-established history of dissent in the Upper Calder Valley – dissent from established religion and always a fight against authority. In its religious aspect this showed itself in the number of ‘alternative’ religions such as Quakerism and Methodists. Quakers, formed in the mid 17th century would meet in people’s homes and at the time this was illegal and prosecutions were common. One of these early meeting houses was Pilkington Farm in Mankinholes. Later John Wesley, founder of the Methodists, visited the tiny settlement in 1755 and by 1814 there was a thriving congregation and a Methodist chapel was built to serve Mankinholes and the adjacent settlement of Lumbutts. But dissenters not only broke away from the established church of England but they also had disputes within their own congregation and, hard as it is to believe looking around the scattered cottages and farms clinging to the hillsides in front of me this was even the case in ‘out here.’ By 1836 so grave was the dispute within the congregation that a break away group set up their own rival chapel at Lumbutts in 1837 only half a mile away! As I stood there on the grassy shelf overlooked by the eagle eye of Stoodley Pike I listened in my mind’s ear for the resounding sound of the church organ because, strange as it may seem, the disagreement had been sparked by the installation of an organ in a chapel in Leeds. The majority of Wesleyan Methodists were opposed to music during the service seeing as a distraction from God. In fact Wesley wrote

Still let us on our guard be found,

And watch against the power of sound,

With sacred jealousy;

Lest haply science should damp our zeal,

And music’s charms bewitch and steal

Our hearts away from thee.”

Charles wrote over 9000 hymns. Lumbutts chapel prospered so much so that demand outgrew the building and so in 1877 a much larger building replaced it, complete with a school underneath. The building’s symmetry with its surrounding carpet of neatly mowed grass gives it a very artificial look on these moors where groups of buildings cluster together at all angles and levels to protect themselves from the storms the area is subjected to throughout the year. With its steeply pitched roof and rectangular footprint today it stands abandoned. In 1904 the church underwent major renovations and the crowning point was the installation of a new organ which became known as The Old Lady of Lumbutts – a huge 3-ton organ. The inaugural recital given on May 6 was given by one W. A Wrigley (!) Mus. Bac. Oxon, the resident organist at Todmorden parish church and the complete refurbishment of the church’s interior was carried out by Messr. Wrigley and sons of Todmorden and Hebden Bridge, direct descendants of non other than Abraham and Sally Wrigley. It is one of very few left in the country and was renovated in in 1989 when villagers raised £11,500 to repair it is still inside I don’t know. Today the damp blue slate roof acted as a mirror reflecting the occasional bursts of sunlight breaking through the wet mist. So the new chapel was only two years old when Abraham was buried in the cemetery at Lumbutts Chapel.

29 April, 1881. Todmorden and district news.

LUMBUTTS. 141 persons partook of tea at this place. The tables were supplied with the choicest well-cooked meats and delicacies by Mrs. Wild, of Mankinholes. The health of Mr. John Fielden, Dobroyd Castle was proposed, and carried most enthusiastically, with musical honours and cheers; “The health of Mrs. John Fielden” and “ Success to the firm of Fielden Brothers ” were duly honoured. After these preliminaries the time was spent in dancing, music and games, in turns. Mr. Young Mitton played on the piano in very good style, and accompanied the singers. The following is a list of songs rendered at intervals: “You never miss the water till the well runs dry,” The twin brothers,” “Camomile tea,” “Verdant fields,” and almost twenty more. During the evening a very nice refreshment stall, provided by Mrs. Holt, of Lumbutts, was placed in one of the class rooms; no intoxicating drinks were admitted. Mr. and Mrs. John Fielden paid visit during the afternoon, and were most heartily cheered. The whole affair was conducted with order and good will, and is likely to be remembered long as a very pleasing circumstance in personal history. Honest John Fielden donated the land.

I’d visited the chapel twice before, once with my children, and had found the grave of Abraham, and his daughter, Mary who died when she was 17 in 1868. There’s a little zippy bus that somehow manages to negotiate the steep road and the hairpin bends up to the village from Todmorden though if it meets an oncoming car someone has to give way and back up. I’d grown up knowing the name Mankinholes because my mum had stayed at the Youth Hostel there in her twenties. I was delighted to be able to visit it today, even though of course, it’s closed due to coronavirus. It’s a wonderful old stone building and today you can book a 2, 4 or 6 bedded room with adjacent bathrooms, all comparative luxury to when my mum was there in the 1940s when there would have been one dormitory for men and another for women, and an outdoor toilet!

As I left the village and started my descent back into the valey my attention was drawn to a large stone with the sign ‘Mankinholes 2000’ carved upon it, together with an engraving of Stoodley Pike, the monument on the hilltop overlooking the village. On either side of the sign were two blocks of stone carved to represent two larger than life sheep with wrought iron horns. As I stopped to admire them and take a photograph a couple came along the path. “Do you like the sheep?” the lady asked. “They’re lovely” I replied. “They were carved for the Silver Jubilee. Me husband made ‘em, didn’t you, dear?” So here I was talking to the sheep carver in person!

After Abraham had died Sally moved in with her unmarried daughter Hannah, 34, a cotton weaver, and her son James, 23, a joiner in a terraced house on Brook Street in the centre of Todmorden, now demolished and a car park. And then in 1883, the three of them are on a boat going to New Zealand! This is remarkable. At the age of 66, Sally boards the ship named Westmeath with her two unmarried adult children, Hannah, 36, a cotton weaver and James 25, a joiner. Not only is this uncharted waters for the three Wrigleys but it’s uncharted waters for the ship for this is her maiden voyage. Built in Sunderland, once dubbed the world’s largest ship building town, on 15 March 1883 The Westmeath sailed from London with cargo and emigrants and a number of saloon passengers, via the Cape bound for Auckland and Port Chalmers. For a time assisted passages were offered by the New Zealand government and between 1871 and 1886 more than a quarter of a million people flooded into the country, three quarters of them sailing directly from the United Kingdom although about 40% of them took a look and moved on.

On more exploration I discovered that Sally’s decision was not so unexpected. Her son Edmund had already emigrated to New Zealand in 1862 at the age of 19 before the mass flood of immigration and her son John followed the following year when he was 25, also a joiner in 1861. Through the wonders of the internet I found Zena Wrigley, an ancestry hunter living in New Zealand whose husband was Abraham and Sally’s great great grandson. Her husband’s father had personal recollections of the Wrigley brothers who emigrated to New Zealand, John, his grandad was a Quaker, a very religious man, and Dad often spoke of him in an endearing way. A gentle man who loved looking after Edward Wrigley (Zena’s father-in-law) as a child, Edward found his own father a strong disciplinarian and found him hard to relate to and so did not speak much about him. Edmund, John’s brother, on the other hand was very much involved with Masonry and so I would imagine Quakers and Mason’s probably would not have had much in common!! The third brother was James, a Methodist minister, his work in those pioneering days is well documented in the Methodist archives and was instrumental in establishing churches throughout the North and South Islands. From Zena I obtained photographs of minister James, Abraham and son John as a child, Sally, John as an old man, Hannah in studio.

According to Zena “Edmund and John were both builders and saw migrating to NZ as a big plus!! To my understanding they paid their own way, John actually travelled with his wife to be and her father. Most early settlers came out in groups through land ownership schemes that promoted pioneering opportunities to buy land and start a new life.” John was a joiner in 1861 census. Before the mass migration in the 1870s there was little to attract prospective immigrants, although some people did. When Mary’s father died in 1840 he left a trail of debt, and Mary became convinced she would benefit from starting all over again by emigrating to New Zealand. Her youngest brother William Waring Taylor emigrated to Wellington in 1842, but Mary first spent several years studying music, French and German, and teaching in Germany and Belgium, before eventually joining him in 1845. Charlotte Bronte wrote of her friend’s departure: ‘To me it is something as if a great planet fell out of the sky’. Not long after her friend’s arrival in New Zealand, Charlotte helped her out by sending £10 to buy a cow.

People were put off by the bad reputation of New Zealand’s climate, its dangerous ‘natives’ and the high costs and perils of the journey. But in 1871 an engineering firm of John Brogden and Sons, brought out 2,712 labourers to work on railway contracts. From 1873 the fare of £5 per adult was waived and travel was free. In addition, New Zealand residents could nominate friends and relatives to come and join them. In England and Scotland local people such as book sellers, grocers and schoolteachers were recruited to spread the word about the benefits of emigration while newspaper advertisements and posters called for married agricultural labourers and single female domestic servants, provided they were ‘sober, industrious, of good moral character, of sound mind and in good health.’ As might be expected 80% of immigrants were under the age of thirty five. “Around that time there was the discovery of gold / coal / beautiful native timbers and so this brought in the miners, the pioneers, the builders, etc.

Where John and Edmund’s family came and settled was in Auckland a thriving city which offered such a huge potential to succeed.” I, too, was under thirty five when I emigrated to the USA. Many emigrants came from Scotland and the Scottish islands and the poet John Betjeman later commentated:

‘All over Shetland one sees ruined crofts, with rushes invading the once tilled strips and kingcups in the garden. “Gone to New Zealand” is a good name for such a scene, because that is where many Shetlanders go, and there are, I am told, two streets in Wellington almost wholly Shetland’. However, by the 1880s the promised land had not lived up to expectations. Those who had come out in the 1870s sent less positive messages home, and free passages were ended. The 1890s became known as The Long Depression and people began to leave. They went particularly to Australia, where ‘marvellous Melbourne’ experienced a boom in the 1880s.

But my story of Sally Wrigley ends where it began, in Lily Hall, for in the summer of 2019 a current resident of Lily Hall spotted a couple looking around the village of Heptonstall. They stopped to take a photo of Lily Hall and so she chatted with them. Knowing that I had ancestors who had lived at Lily Hall named Wrigley, some of whom had emigrated to New Zealand, she immediately contacted me and later that day I found myself in the company of a lady who has the same great great great grandfather as me – James Wrigley, 1778-1846, Sally’s father-in-law.

“My great grandfather was John Wrigley born at Heptonstall, my great, great grandfather was Abraham Wrigley, and my great, great, great grandfather was James Wrigley. I am the daughter of Edward Nicholson Wrigley, whose father was William Wrigley, son of John Wrigley.All born at Heptonstall, so it is a special place for me.” wrote Ruth Morgan.

An hour later saw the current residents of Lily Hall and James Wrigley’s descendants, two from New Zealand and one from Bolton via the U.S.A having tea in what had been Abraham’s home in 1837 when he married Sally at the church five minutes walk away.

Recent Comments