Thomas Wardle Gledhill

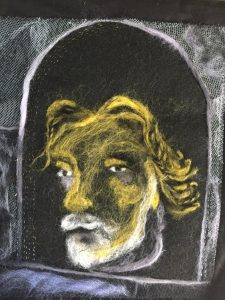

Ever since I received a photo of my great uncle Thomas from a new-found relative on Ancestry.com I’ve been haunted by his gaunt face, staring out. It’s a face that tells of hardship and sorrow so I decided to delve a little more into his background, and perhaps find out if what I was reading in his face was born out by what I could find out about his life.

Sure enough I find that by the date of his baptism at Halifax minster, August 12, 1863 twelve days after his birth on July 28, his mother, Mary nee Peel, had already died. Within 2 years his father George remarried, this time to Charlotte Haigh. The turbulence of their marriage and George’s various prison sentence have been described in my chapter about George. However, Thomas’s middle name has puzzled me for a while now. It surely is a surname, possibly indicative of his ‘real’ father. And then I found ‘the missing link.’ I’ve just noticed that on the 1881 census that when Sarah Gledhill was living at 51 Battison St in Halifax the next door neighbour at # 61 was James Gledhill Wardle. There MUST be some significant connection here. It can’t be a coincidence. So possibly James was Thomas’s biological father. OK. But why does James have Gledhill as a middle name? Argh! The plot thickens. That requires more delving. So I spent an entire evening finding out about the life of James Gledhill Wardle, born in 1843 to mother Isabella who was born in Soyland, Halifax. I traced him from 1861 until his death in 1919 and there’s no accounting for his middle name being Gledhill. I do know that he was christened with that name but none of his siblings have that as a middle name. So I’m none the wiser. Getting back to Thomas Wardle Gledhill George and Charlotte subsequently had two children Abraham, born 1866 and Sarah, born 1868. Did they realize the biblical significance of these names?

By the time he was 8 years old Thomas was living with his grandparents John and Harriet Gledhill at 1 and 2 Regent’s Court, Orange Street in Halifax. This is now a car park though Orange Street still parallels a new road by the Orange Street roundabout. At 61 and 58 years old his grandparents were quite elderly to deal with an 8 year old. Their own children John 18, and Maria 15 were working. John as a drayman like his father, and Maria as a worsted twister.

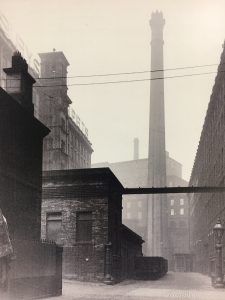

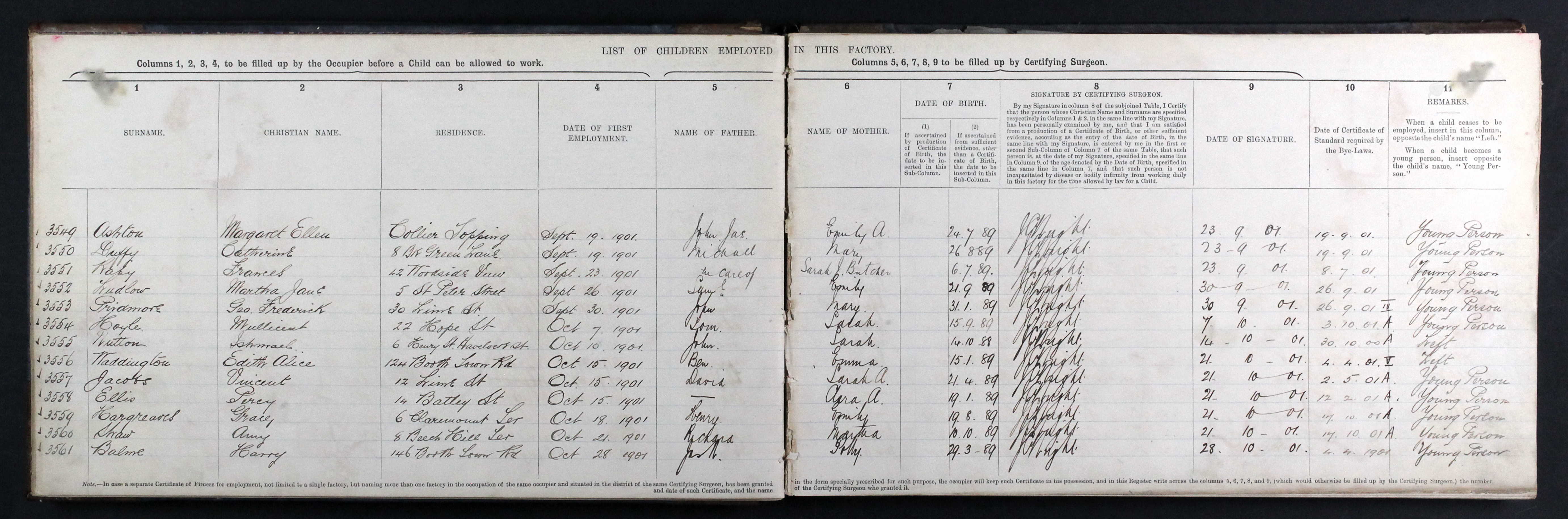

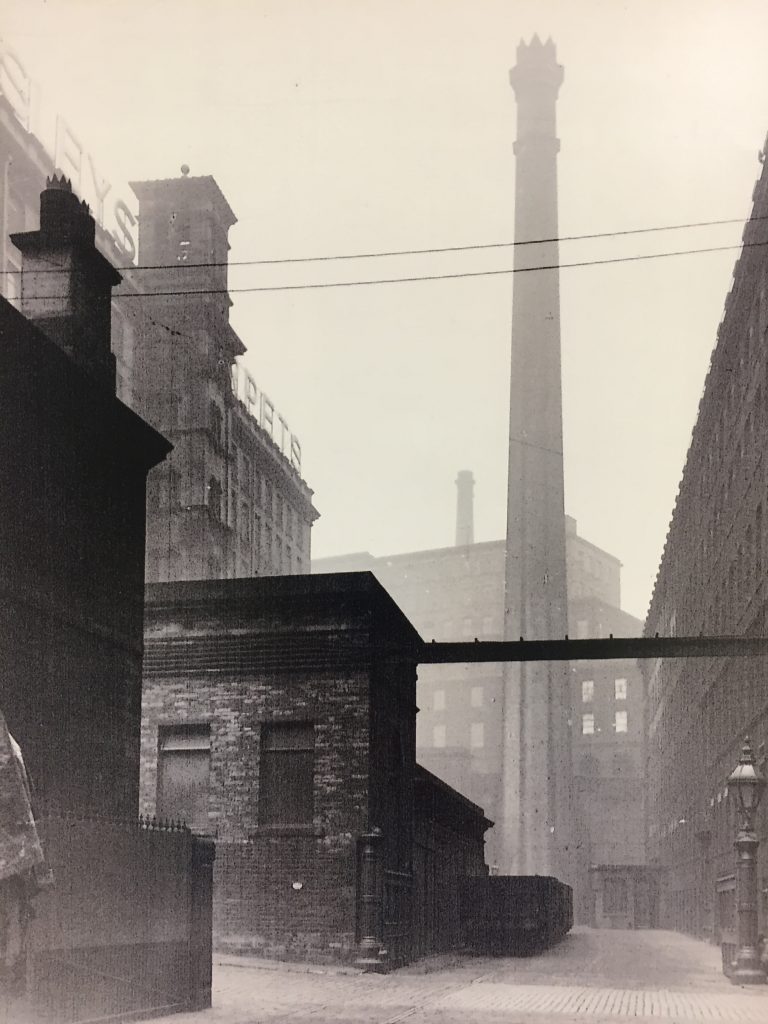

On Aug 31, 1876 there is a record of Thomas being employed at Crossley carpets, one of 6 children between 13 and 18 years of age who took up employment that day in what was then the largest carpet manufacturer in the world, employing 5000 workers. John Crossley (1772 – 1837) founded the firm at Dean Clough in Halifax. By 1837 the firm had 300 employees and the fourth largest mill in Britain. Following the death of their father, the firm was inherited by his three sons, John, Joseph and Francis.

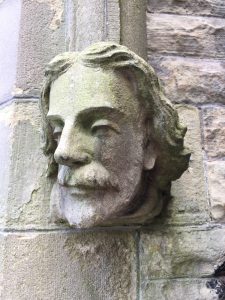

Francis Crossley (1817 – 1872) was responsible for the company’s rapid expansion throughout the mid-nineteenth century. He pioneered the development of steam-powered carpet manufacturing, which gave the company an enormous advantage in terms of cost of production. Licensing the use of their patents to other carpet manufacturers brought in substantial revenues from royalties alone. Unusually for the time, Francis Crossley operated a policy of paying women equal wages to men for doing the same job. Many of the Crossley family values were inspired by their Congregationalist faith.

By 1862 Crossley & Sons was the largest carpet manufacturer in the world. In 1864 the firm became a joint-stock company, with the primary aim of allowing its 3,500 employees to become shareholders. 20 percent of the company was sold to the employees at preferential rates. They were perhaps the first large industrial employer to profit share with their employees.

In 1868 John Crossley & Sons was the largest publicly quoted industrial company in Britain, with an ordinary share capitalization of £2.2 million (about £220 million in 2014). 5,000 people were employed. By 1872 the company had annual carpet sales of £1.1 million, including exports to the United States valued at nearly £500,000. The buildings at Dean Clough Mill covered 20 acres, where concentration of production at a single site lowered costs.

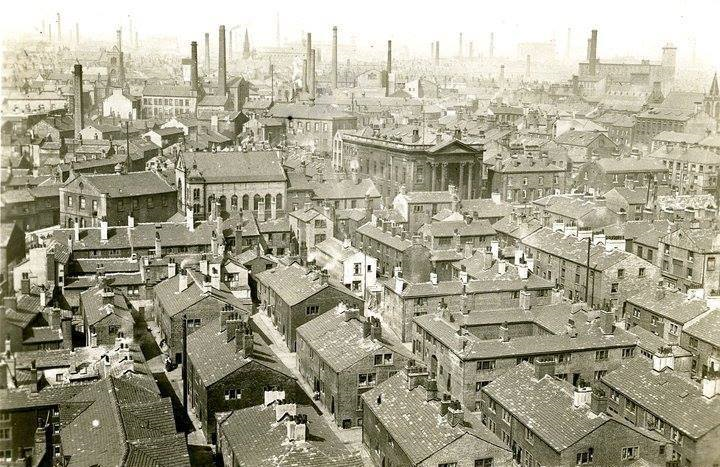

By the time of the next census in 1881 Thomas was living with the Thomases: his aunt Rachel and uncle George in Milk Street, Halifax. Milk Street was part of ‘the City.’ The City was a densely populated area at Cross Fields bounded by John Street to the south, Great Albion Street to the north, Orange Street to the east, and St James’s Road to the west.

It was built at the beginning of the 19th century, and became a slum area with a higher death rate than the rest of the district. There were an estimated 780 people living in a maze of back-to-back houses, courtyards, dimly-lit shops, and narrow streets. On 27th February 1926, the Ministry of Health approved the demolition of the area. The property was demolished in 1926. The site remained empty until 1938, eventually making way for the bus station and the Odeon. Thomas’s job appears to be ‘printer in carpets.’

In Feb 6 1888 at Halifax Minster he married a widow Ruth Dean (nee Bates) both of Crossfield Halifax, another part of ‘the City.’ Thomas’s hand look very unsteady on his marriage certificate. I wonder if he was literate. The 1891 census finds the family at John Street, another part of ‘the City.’ Thomas is a tin plate worker. They had two children, Willie and Minnie but five years after their marriage Ruth died in 1893 at the age of 30 and a year later on 19th August 1894 Thomas married Sarah Jane Veal at St Thomas’s church in Charlestown, Halifax. Thomas was 31 but at 32 it was a very late first marriage for Sarah. However Sarah had already given birth to a son Frederick Horsfall Veal who was baptized on 12 Nov 1884 at All Souls, Haley Hill, Halifax. That’s the church where my great aunt Lil and her husband Bart are buried and Sarah and I went to find their grave in the summer of 2017. There is no father indicated on the baptism record meaning that Sarah wasn’t married. Presumably Frederick’s biological father’s surname was Horsfall.

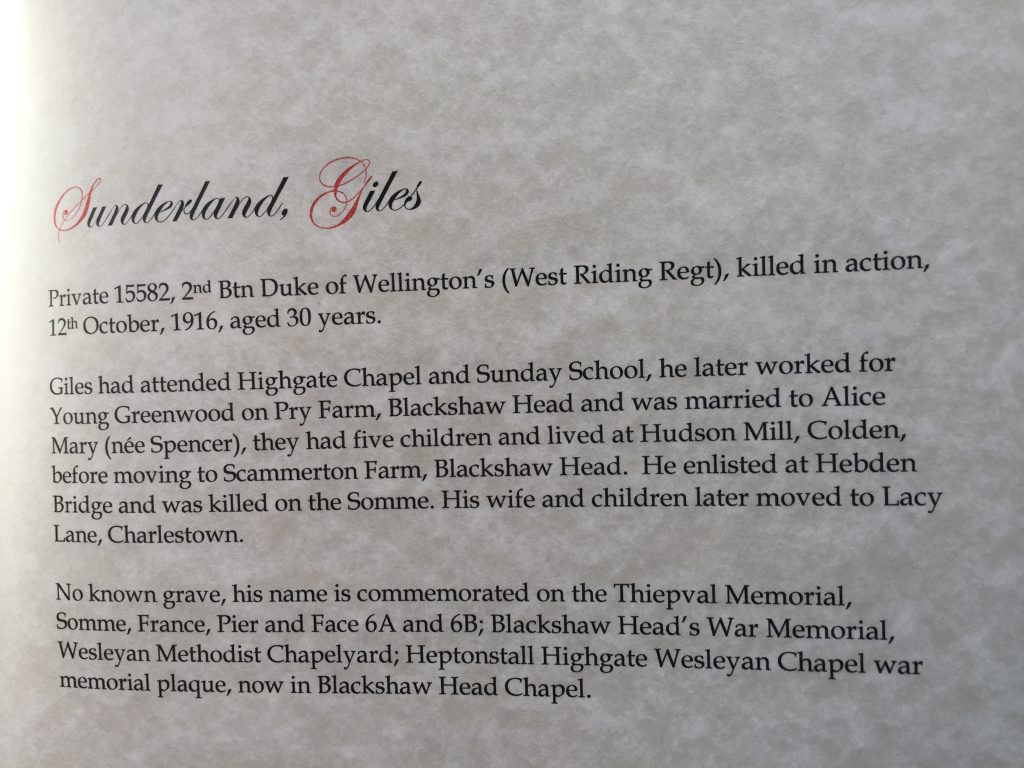

Thomas was living in Fleet Street, and Sarah in Pitt street at the time of their marriage. Both streets are in the slum area of ‘the City.’ A year later their first daughter was born, Gladys (18895-1962). 1901 sees Thomas and his family at 10 James Street, also in ‘the City.’ His occupation is given as ‘scavenger’ (corporation) with three children Willie 13 and Minnie 10. Ten years later, 1911, the family are at the same address and Thomas is now a labourer on the road (corporation). Now Sarah Jane’s son by a previous relationship Frederick Horsfall Veal is living with them. He’s 26 and a fish fryer! Frederick went on to become a private, 2nd/6th Bn. in the Duke of Wellington’s West Riding Regiment, was killed in action on 3 May 1917 and is commemorated at Arras memorial cemetery in France. From army records I believe he saw action in France, Belgium, Germany and Gallipoli.

10 months later Thomas himself died, aged 54, at 20 Grant Street in the centre of Halifax and is buried at St James’s church in Salterhebble. It’s odd to realise that this man was my grandma Florence’s uncle, her mum’s step-brother, just like it’s so difficult to realise that Thomas’s father, George (of Wakefield jail fame) was my grandma’s granddad. There was always tension at family get togethers between my mum’s mum and my dad’s mum. My dad’s mum lived in a semi and my mum’s mum lived in a terraced house but I was also aware that my mum’s mum thought that her sister-in-law lived ‘above her station.’ I wonder if she knew about George’s prison time and the poverty that affected Thomas’s family.

After my cappuccino and cake I wandered around the galleries for a while and my eye was taken by a new exhibit. Well, that’s a mild way of putting it. I was stunned by it. The subject was wreaths, which, in my books, didn’t sound too interesting, but these celebrated the living, the dead, the lost. One included display included objects that mothers attached to babies they left on charity doorsteps. Another was a wreath wrapped around a hanged man. The one that took my attention was one about a fallen soldier, including family photos, and old pennies to close his eyes. The kit box supporting him listed the number of people killed and wounded in WWl.

After my cappuccino and cake I wandered around the galleries for a while and my eye was taken by a new exhibit. Well, that’s a mild way of putting it. I was stunned by it. The subject was wreaths, which, in my books, didn’t sound too interesting, but these celebrated the living, the dead, the lost. One included display included objects that mothers attached to babies they left on charity doorsteps. Another was a wreath wrapped around a hanged man. The one that took my attention was one about a fallen soldier, including family photos, and old pennies to close his eyes. The kit box supporting him listed the number of people killed and wounded in WWl.

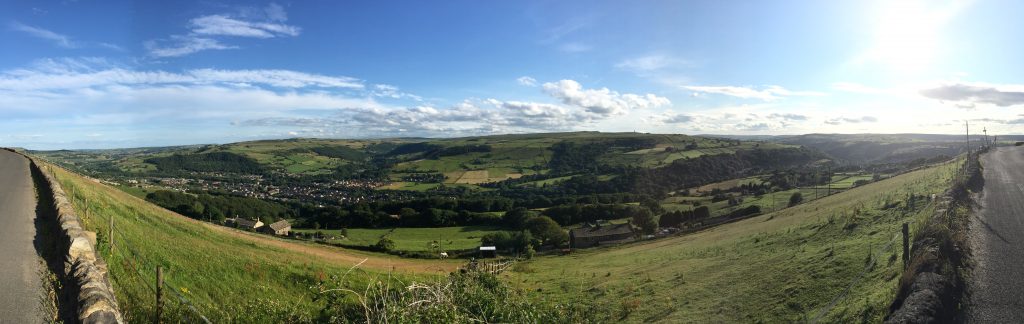

around doing the ‘listing’ and the doors to this chapel were locked that day. It looks austere and dull from the outside so he didn’t list it. Thank goodness! If we’d have been Grade 1 or Grade 2 listed we wouldn’t have been able to do all the things we have done – like build the extension on the back.” As we chatted a man came in to collect some posters and as Dot explained why I was there he invited me to a special celebration of the people of Blackshaw who returned from fighting in WWl but then had to deal with ‘a living hell’ for the rest of their lives. He introduced himself as Tim, and he also told me about A Beacon of Light that’s going to be lit on Great Rock above Eastwood featuring a handbell choir on the evening of Armistice Day. “I’ll see if I can arrange transport, if you need it” he offered. When he’d gone Dot explained that ‘Tim’ is none other than Mr Timothy James Pitt, Vice Lord Lieutenant, one time High Sheriff of West Yorkshire whose interests include ‘country pursuits, classic cars, gardening, golf, breeding Alpacas.’ http://www.westyorkshirelieutenancy.org.uk/vice-lord-lieutenant/

around doing the ‘listing’ and the doors to this chapel were locked that day. It looks austere and dull from the outside so he didn’t list it. Thank goodness! If we’d have been Grade 1 or Grade 2 listed we wouldn’t have been able to do all the things we have done – like build the extension on the back.” As we chatted a man came in to collect some posters and as Dot explained why I was there he invited me to a special celebration of the people of Blackshaw who returned from fighting in WWl but then had to deal with ‘a living hell’ for the rest of their lives. He introduced himself as Tim, and he also told me about A Beacon of Light that’s going to be lit on Great Rock above Eastwood featuring a handbell choir on the evening of Armistice Day. “I’ll see if I can arrange transport, if you need it” he offered. When he’d gone Dot explained that ‘Tim’ is none other than Mr Timothy James Pitt, Vice Lord Lieutenant, one time High Sheriff of West Yorkshire whose interests include ‘country pursuits, classic cars, gardening, golf, breeding Alpacas.’ http://www.westyorkshirelieutenancy.org.uk/vice-lord-lieutenant/

Recent Comments