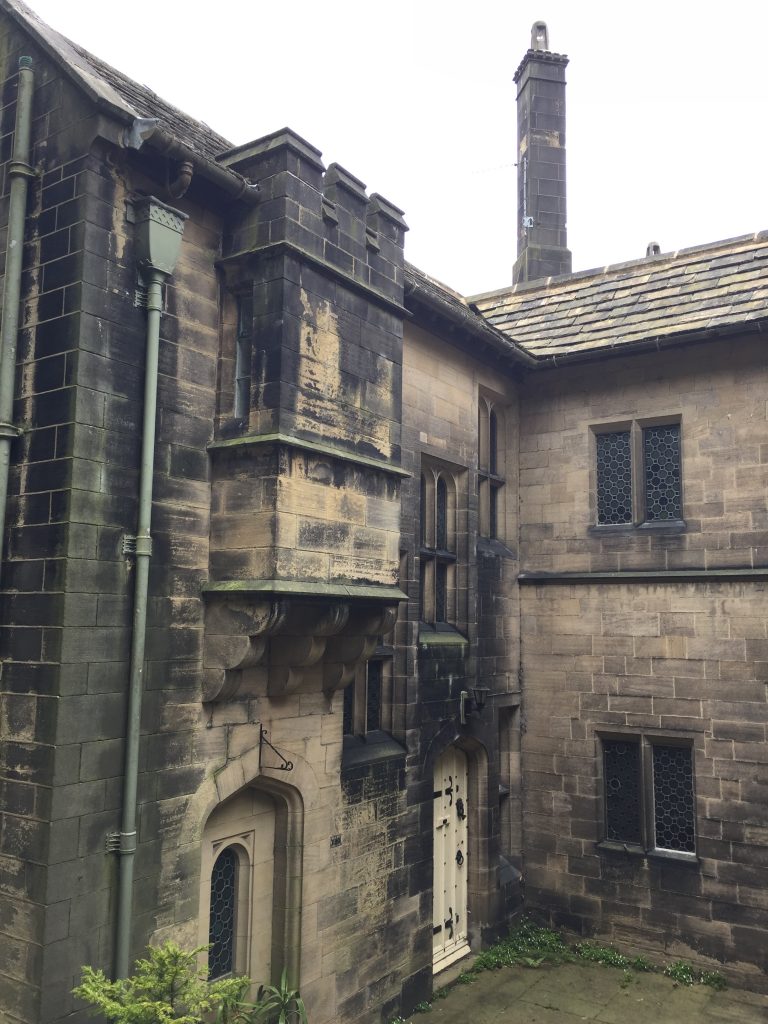

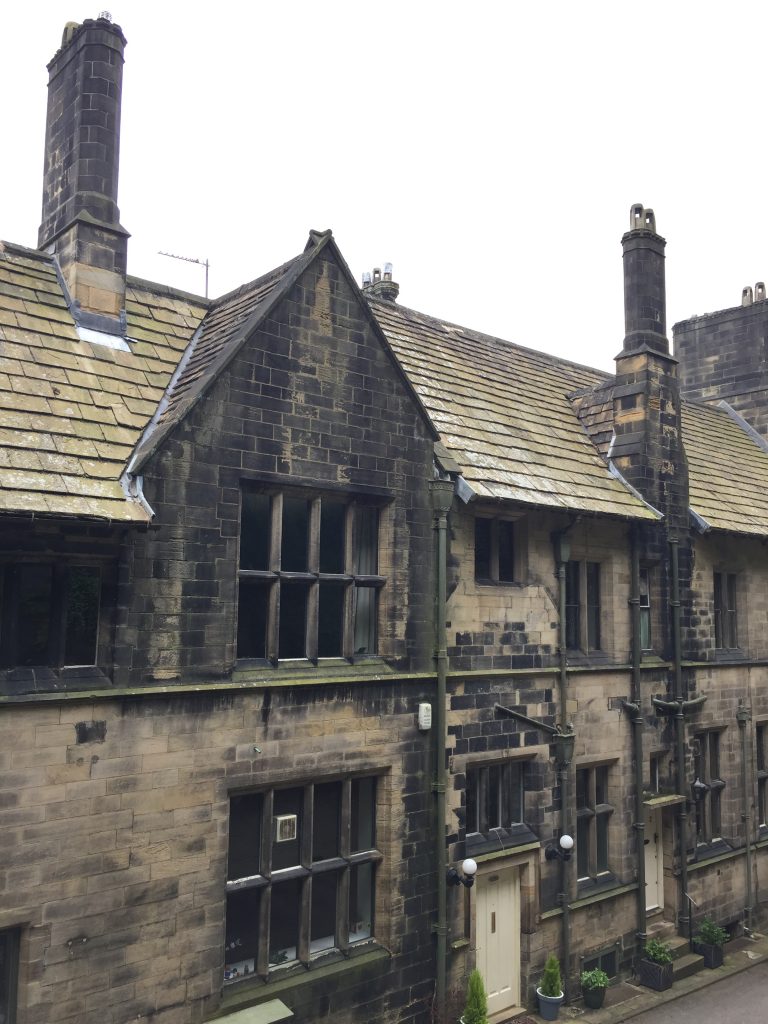

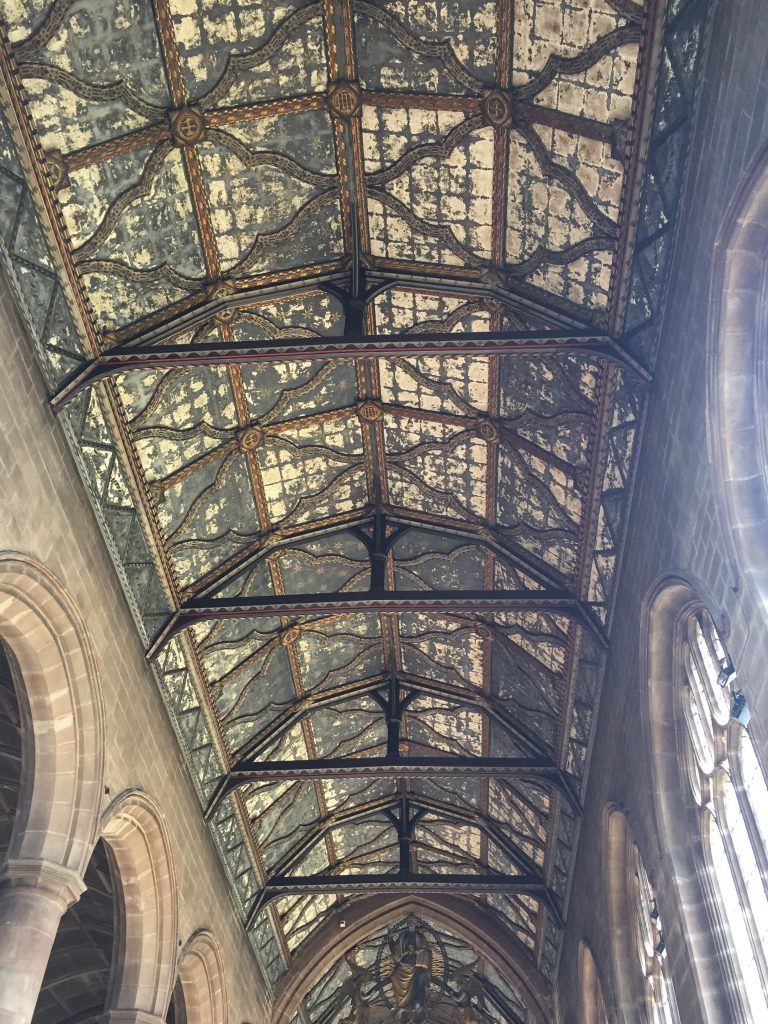

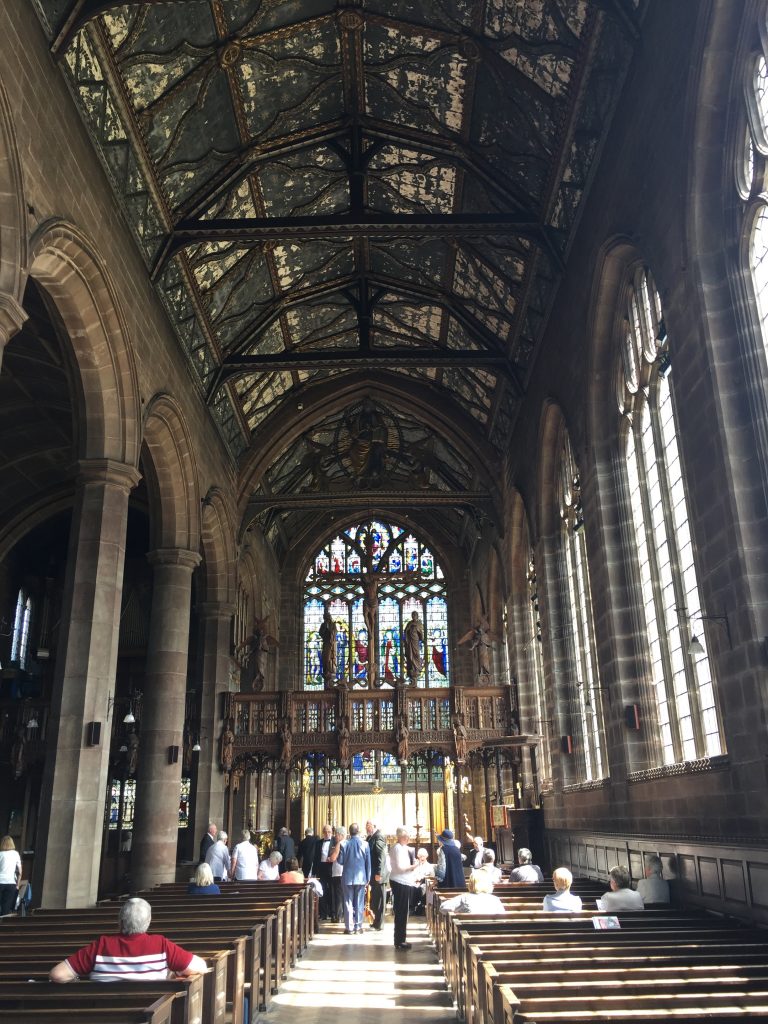

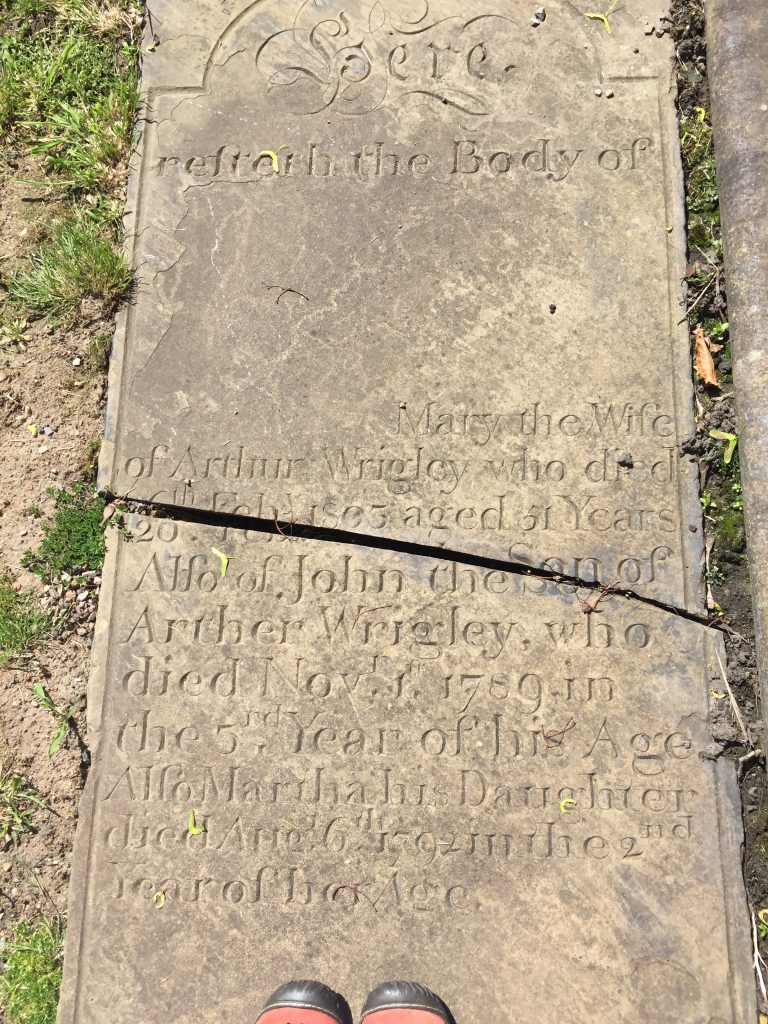

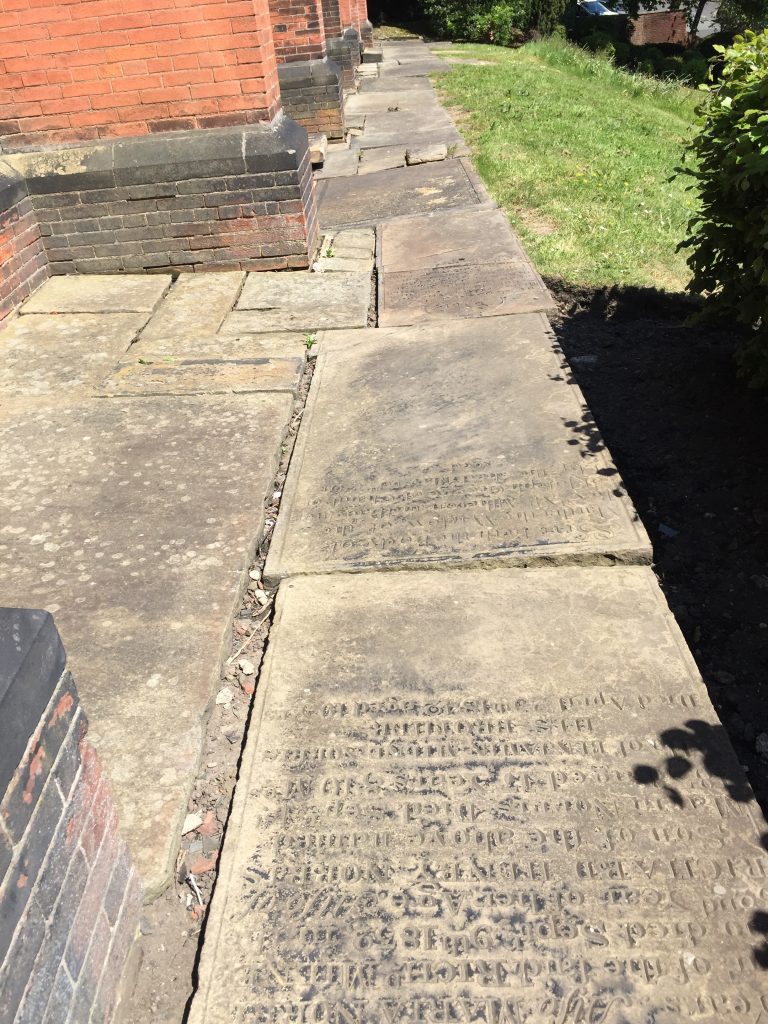

I can trace the Barraclough side of my family with a fair degree of certainty to Abraham Barraclough who was born in 1640. He was my great, great, great, great, great, great, great, great grandfather. Someone in Calgary Canada has done extensive research on the Barracloughs of West Yorkshire and it’s published online as ‘A Family Orchard.’ Abraham was 63 at the time of his death and he’s buried at St. Peter’s churchyard, Sowerby. However, there’s no record of that grave on Find a Grave. When I first learned of my connection with the Barracloughs of Sowerby, when I visited in the summer of 2016 I was eager to go to the village and see the church. I found, online, a book about growing up in Sowerby by one Jean Illingworth. I arranged to meet with her. She gave me a wonderful guided tour of this tiny hilltop village overlooking the Calder Valley. She’d arranged with the church warden to be there and open the church for us. Outside it’s a rather unusual building and it reminded me of a prison! Inside the ornate plasterwork is some of the finest examples of that craft outside London. I have yet to find Abraham Barraclough’s gave.

Abraham’s great great grandson was David Barraclough, born in 1767, and baptized at St. Peter’s Sowerby on December 18, 1767- son of John. The next time he pops up is on his marriage to Mary Hirst on July 24, 1792 in Halifax minster at the age of 25. According to Malcolm Bull Mary came from Sowerby. They had 5 children: Jemima 1796-1855, Joseph, b. 1798, David, born 1800, Elizabeth born 1801 and James b 1802. His father died two years later and his mother the following year. In 1838 there’s a possible marriage, according to Malcolm Bull, but it seems unlikely. He’s 78, a wool sorter and a bachelor at the time of this marriage. According to Malcolm Bull Sarah came from Leeds, they had two children Eliza, born 1805,m and Susan, bornt 1806 who married James Satchwell. The family lived at Croft House, Stainland.’I walked straight past it yesterday without knowing that! However, by the 1841 census he is 78, a minister, living with Sarah Barraclough , 55 and Eliza Barraclough, 35. Unfortunately the 1841 does not list the relationships of people living together. Living with the Barracloughs at this time are James Satchwell, 25,tailor, Susan Stachwell, 30 and Eliza Satchwell, 3. This set up would suggest that Susan Satchwell is David or Sarah’s daughter. SURE ENOUGH I FIND A MARRIAGE OF JAMES SATCHWELL (tailor) TO SUSEY BARRACLOUGH AT HALIFAX MINSTER ON JULY 1, 1836.

Now according to Find a Grave’s reliable website David was a ‘prominent clergyman of the Wesleyan methodist faith in both England and Ireland. Pastor at Stainland old independent chapel.’ According to the Malcolm Bull website: ‘This chapel was built in 1814 by a group who had left Stainland Independent church after there had been a disagreement over the reading of prayers. Another site says that in 1792 he was a preacher in the parish of Charlmont, Armargh, Ireland. The chapel in Wade Street, Halifax, was built for him. He left the Methodists at South Parade chapel and became minister at St Andrew’s, Stainland in 1806.’ HOWEVER, according to the genuki.org.uk in The Stainland Congregational church history up to 1868 ‘a chapel was erected here about the year 1755, and a congregation was formed comprehending christians of different denomination, principally wesleyans and Independents. The first minister known was Rev S Lowell who left Stainland for Brighouse in 1782. The next was Rev John Bates who removed to Mixenden in 1793. To him succeeded Rev Samuel Barraclough who afterwards joined the new connection.(oh oh! A different Barraclough).( Malcolm Bull has ‘Samuel Barraclough 1756-???, son of John. 1726-1794) who was son of Abraham who married Martha Wrigley.)

‘He was a pioneer Methodist preacher who marrried Mary Crossley on Feb 20, 1776. Rev Mr Hanson followed. He removed to Shelley in 1812.’ From the Appendix to Congregationalism in Yorkshire by James C. Miall, 1868.

So, back to the chapel at Wade Street. It was built as an independent chapel for a group of people who had formerly been Wesleyan Methodists, with David Barraclough as their leader. They left and set up shop in Stainland.

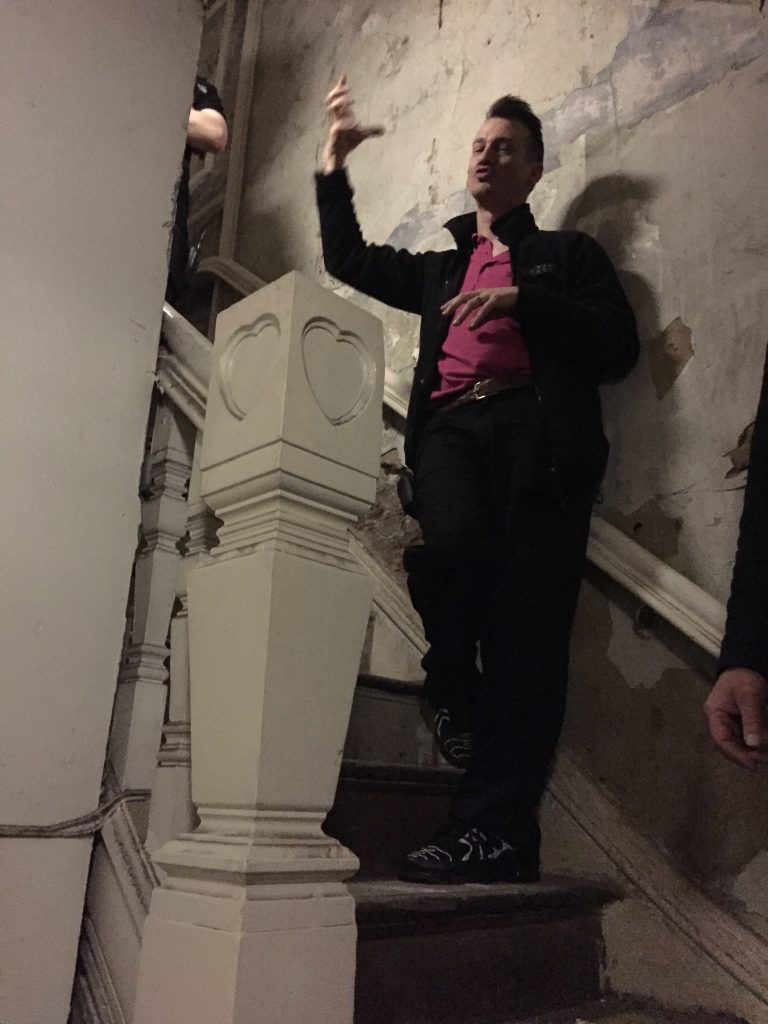

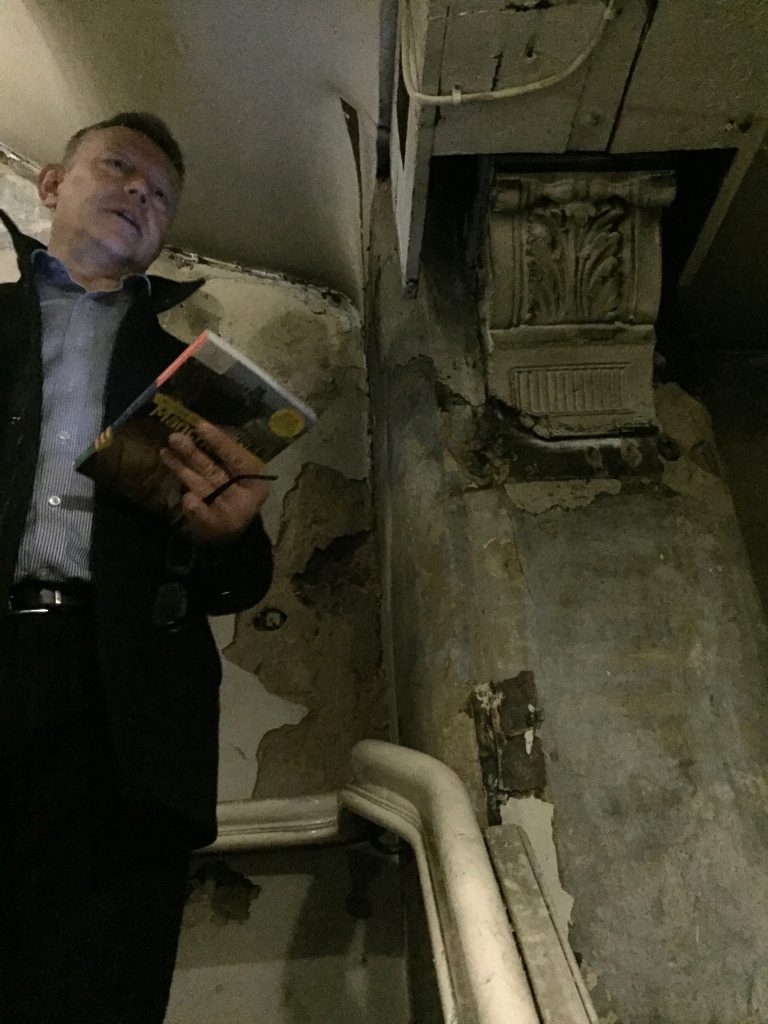

The church there, which is now St Andrew’s, was built as an independent chapel in 1755, a simple rectangular building with 4 plain bays with rounded arched long windows. The pulpit would have been on the South side of the church. A fireplace was in the north corner. The church was enlarged, the chancel added, and a tower added to the designs of Charles Child in 1840, when the church was taken over by the Church of England. The present vicar described the tower as an ‘animal made up by a variety of people, like an elephant.’They also covered the lower part of the windows because the long windows reeked of methodism. There is a balcony on the west end. It’s a grade 2 listed building.

Fr Rodney Chapman brought out photos for me to see what the church would have looked like before it became C of E. It’s a perpetual curacy which means that the church cannot close while Fr Rodney is the incumbant. However, as he told me, when he retires . A lady approached the organ and I chatted with her. She’d been the organist at the church for many years but had resigned six years ago.She’s now practicing for her organ diploma.

I had chosen to visit the church on Community Cafe day, a monthly activity where ‘full breakfasts, light bites and home bakes’ could be enjoyed. The welcoming smell of bacon was wafting through the doorway as I approached and I when I saw others tucking in I couldn’t resist. It was the best bacon I’ve had in ages! It was nice to see many mums and toddlers at the breakfast. A play area had been set up for the kiddies and one little boy is going to be a great percussion player when he gets older!

One of the ladies I chatted to now lives in the old vicarage. Fr Rodney then brought out a mace with George lll’s coat of arms (king 1760-1820)— and a matching truncheon – a policeman’s? He sportingly allowed me to take his photo wielding both!

The morning’s church activities drew to a close at 11.30 and I set off to explore the area. This is an area I don’t know at all. I’ve only driven through Stainland a couple of times on the way to my clarinet choir, and on the 901 bus to Huddersfield which goes over the hilltops from Hebden Bridge. It’s 3 1/2 miles from Halifax and 5 from Huddersfield. Apparently Stainland’s beginning is very much like that of Heptonstall and Sowerby: a hilltop town, primarily handloom weaving and farming, which dwindled in size during the industrial revolution when the mill was built in the valley, powered by water. In 1848 there were 2 mills for making pasteboard used in woollen manufacture.There were 3 coal mines in the area and some extensive stone quarries. Stainland was built on a pack horse route and its name means stoney ground. The name appears in the Domesday book as Stanland. It’s essentially a linear village, all of the principal buildings facing the road which forms a central spine. Just across from the church is an ancient medieval cross but its age and original function are lost in the aeons of time. Perhaps it was a preaching post. Or it could have been a boundary marker.

I intended folllowing a printed walker’s map given to me by a colleague and I set off along a path bordered with clouds of cow parsley which led past allotments. The next valley, Black Brook Valley, soon opened up beyond me and before I headed down the steep side I paused to look at the outcrop of rocks, Eaves Top quarry. The path led across Halifax Golf course on which a few golfers could be seen in action. I checked to make sure no stray balls were hurtling towards me before heading across one of the greens towards a small wood. Here the path became increasingly steep. It was almost one of the ‘sit down’ scrambles that I’m famous for! However, I managed to keep upright, just, before coming to an open field. I couldn’t see a path anywhere across it so I followed some tractor tire marks to a wall, but there was no way over the wall, so I followed the wall until I came to a gate. This was obviously a gate into a private garden of a large house, but I reckoned that there’d be an exit to the garden on the other side where a could see a paved pathway. No sooner had I entered the garden but an “Oi, you!” came wafting across the garden from the garage. A man appeared, “Good job the dogs didn’t go fer yer, luv!” “I’m lost.” “Ee, I can see thee are.” I drew out my map and pointed out that I couldn’t find the footpath across the field so I’d followed the tire tracks. “What yer doin’ on yer own out ‘ere?” “Walking,” I suggested. “Ee thee’s a gam lass an all!” He pointed me in the right direction and off I went. Just at the bottom of the field was Gateshead mill, now undergoing major reconstruction. Believe it or not it was at this mill that the first transatlantic cable was manufactured!

My intended walk followed Black Brook for a little while before climbing steep back into Stainland via Beestonely, but, number one, the riverside path was full of cows, and two, I didn’t fancy climbing back up that hill. That would definitely have been a ‘hand and knees’ job. Why, oh why, don’t descriptions of walks around here give some idea of the steepness of the terrain? This pamphlet had been produced by the Friends of Calderdale’s Countryside. Instead, I followed a path up the other side of the valley and waited half and hour for a bus into Halifax. It took me through some lovely countryside with sweeping vistas over the valley – definitely worth another ride sometime.

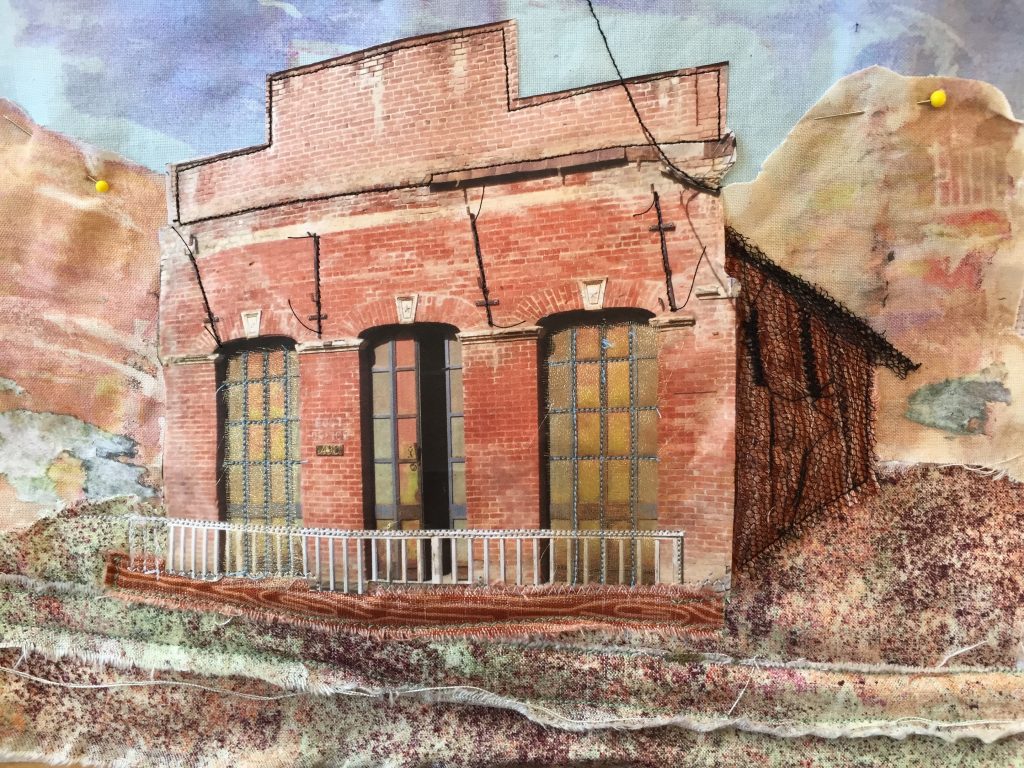

As I waited for the bus back to Hebden Bridge I took a closer look at Halifax bus station. After all, it was built in the shell of my gt gt gt gt uncle’s church. It was built as an independent chapel for a group of people who had formerly been Wesleyan Methodists, with David Barraclough as their leader. Sion Congregational Chapel was an Independent chapel built in 1819, with seats for over 1000 and a schoolroom in the basement. New school buildings were added in 1846 and 1866. David Livingstone gave a sermon and a lecture here in 1857. In 1959, the chapel and the school closed. The building was dismantled in 1984 and rebuilt with the facade included in the new Halifax Bus Station!!

Recent Comments