DEATH BY CHAMBER POT 1898 Can a tale be harrowing and comical at the same time? Is this story a candidate for the Darwin awards? The newspaper heading had it all: ‘The Blackshaw Mystery – Threat with a loaded gun – Disgraceful and sickening behaviour.’ At the age of 71 Ezra Butterworth was found by the postman barely breathing on his kitchen floor in a pool of blood. With the assistance of a neighbouring farmer the two got Ezra settled in his bed but he died later that same evening. Tragic though this sounds the inquest into this unfortunate event was not devoid of a lighter side. One of the witnesses at the inquest was John Whitaker a fustian cutter of Stubb, Mytholmroyd who had been staying with Ezra for the previous three weeks. One night another man joined John and Ezra and, according to the newspaper report, John retold a strange scene. ‘ “We all slept together.” Coroner: “Was it cold that night?” (Laughter) “No sir, I thought it very warm” (renewed laughter). We frequently stayed in bed together til 4 in the afternoon. I have persuaded him to stay in bed late telling him that it would save money.”

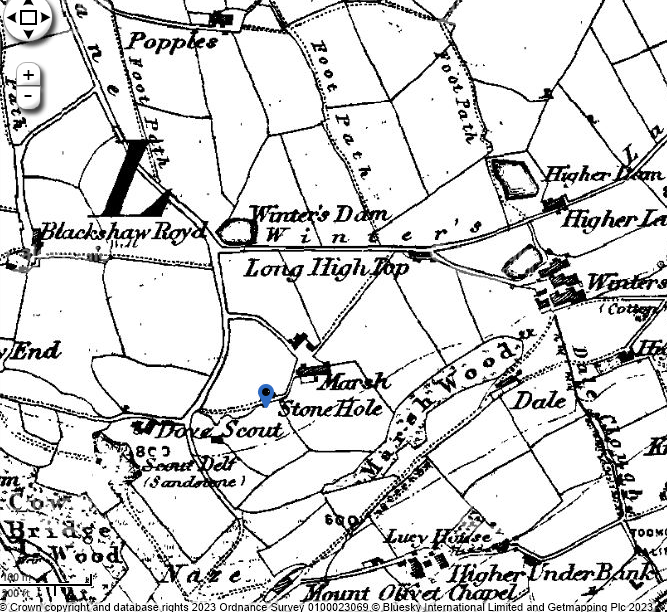

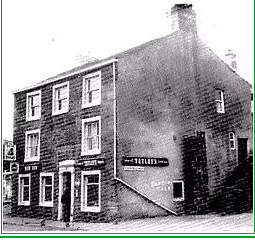

About 10 days before his death the John and Ezra had been drinking at the Blue Ball, Blackshawhead, a pub now closed but I thought this would be a good place to begin my journey into Ezra’s life and his premature demise. In the early 1800s the hilltop village of Blackshawhead had a population of around 4000, four times as many inhabitants as it does today. It was a thriving community, 1300ft above sea level, and an important resting point for travellers on the Long Causeway, a major packhorse route between Halifax, Yorkshire and Burnley, Lancashire. As such the village provided several inns for the packhorse travellers, and, over time a post office, at least two cafes and other shops took root here.

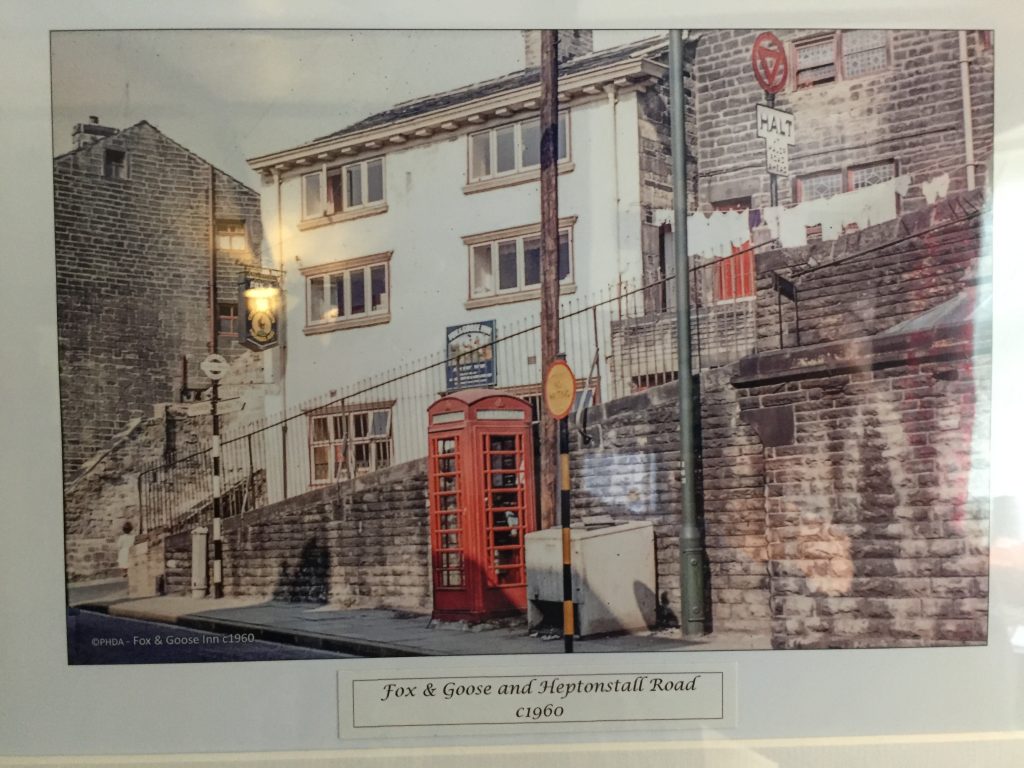

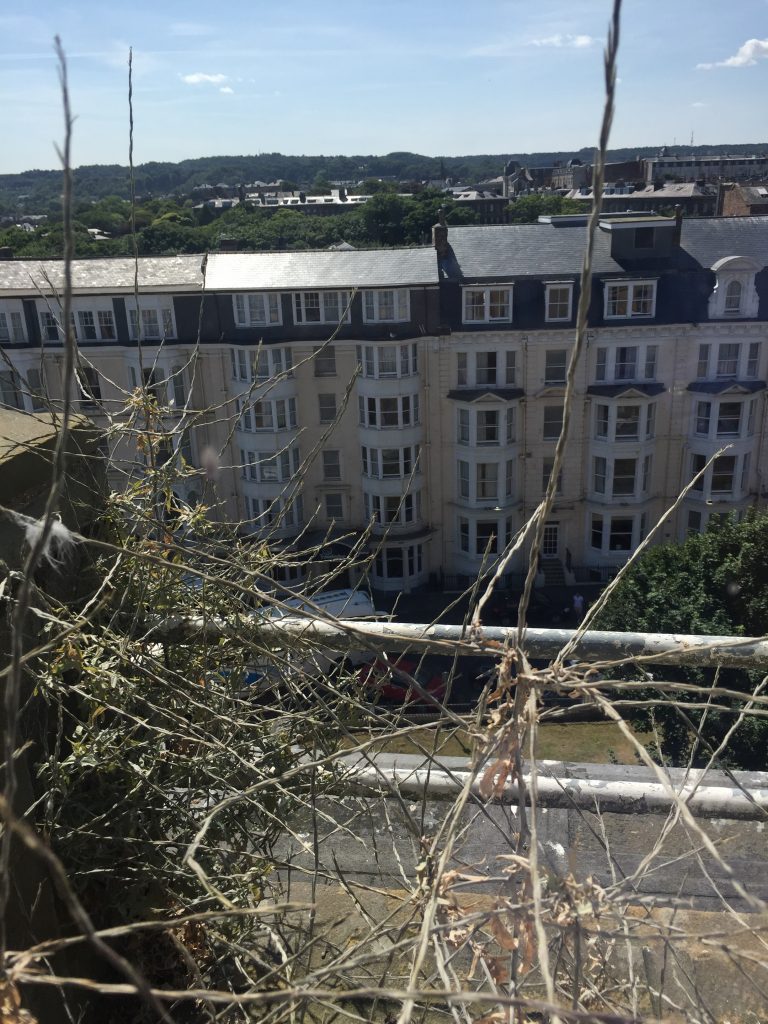

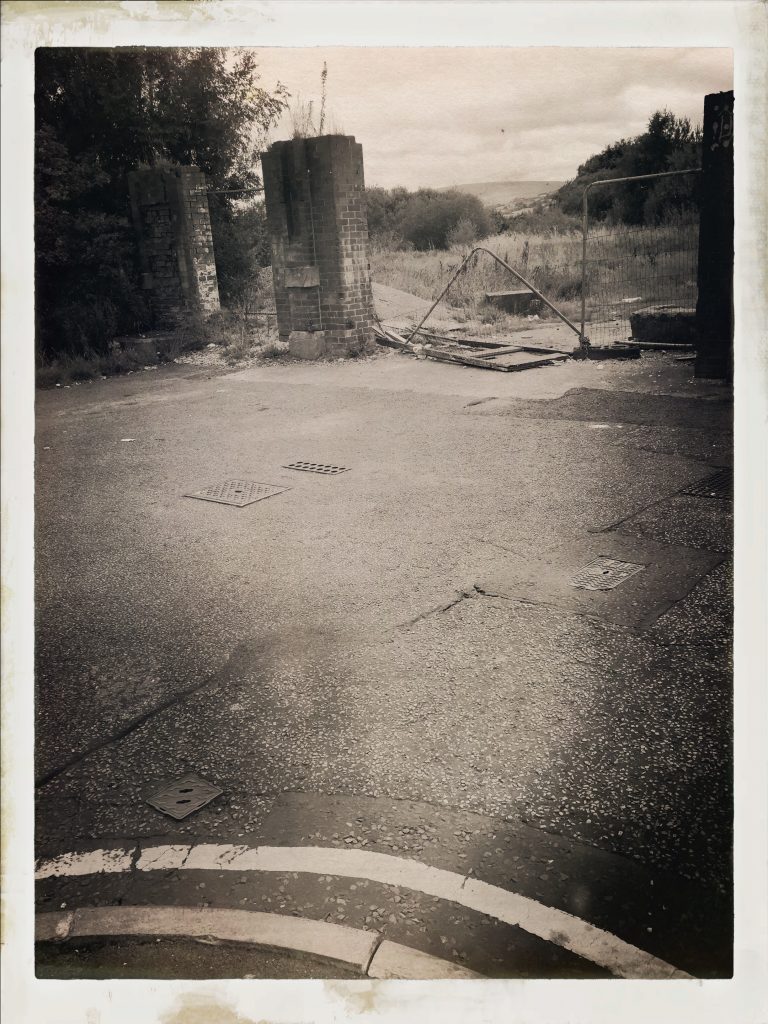

Today, unlike Heptonstall, a similar hilltop village clinging with true Yorkshire tenacity to its one post office, tea room and two pubs, no pubs or shops remain in Blackshawhead and it’s become commuter land for people working in Manchester and Leeds for indeed, the views in all directions from the village are truly wonderful. The hourly bus from Hebden Bridge terminates between the former Shoulder of Mutton, where the inquest into Ezra’s death was held, and the former Blue Ball inn. As I alighted from the bus on this late summer afternoon I regretted that the inn had closed its doors many years ago. A pint of cool cider would have been just perfect at that moment, especially with such a wonderful view laid out before me. The inn, so central to Ezra’s story is now Blue Ball cottage, the end house in a blackened stone terrace with its mullion windows looking bravely out onto the Calder Valley. As the bus disappeared into the distance there was not a sound to disturb my thoughts on this remote hilltop as I recalled the events leading to Ezra’s death. It was December 1898. Ezra and John Whitaker had been drinking at the Blue Ball. On his way home Ezra fell down and John went back to the inn and, with assistance from the landlord’s son, they managed to get Ezra home, and settled him in his bed. I wanted to retrace Ezra’s stumbling steps from the inn to his home at Hippins and it wasn’t difficult. Almost directly opposite the Blue Ball is Davy Lane, a pleasant lane on this sunny day leading gently down towards the Calder Valley but in December 1898, however, it would have been dark, pitch black, possibly icy. In February 2018 I’d taken the first bus up to the village after a terrific snowstorm.

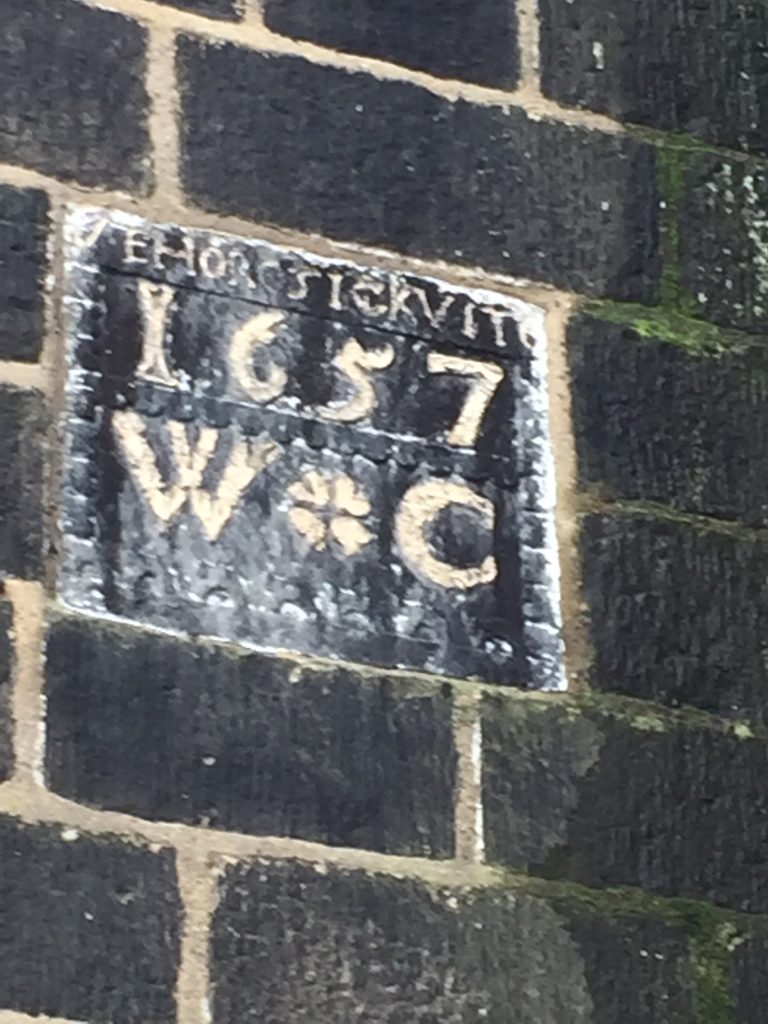

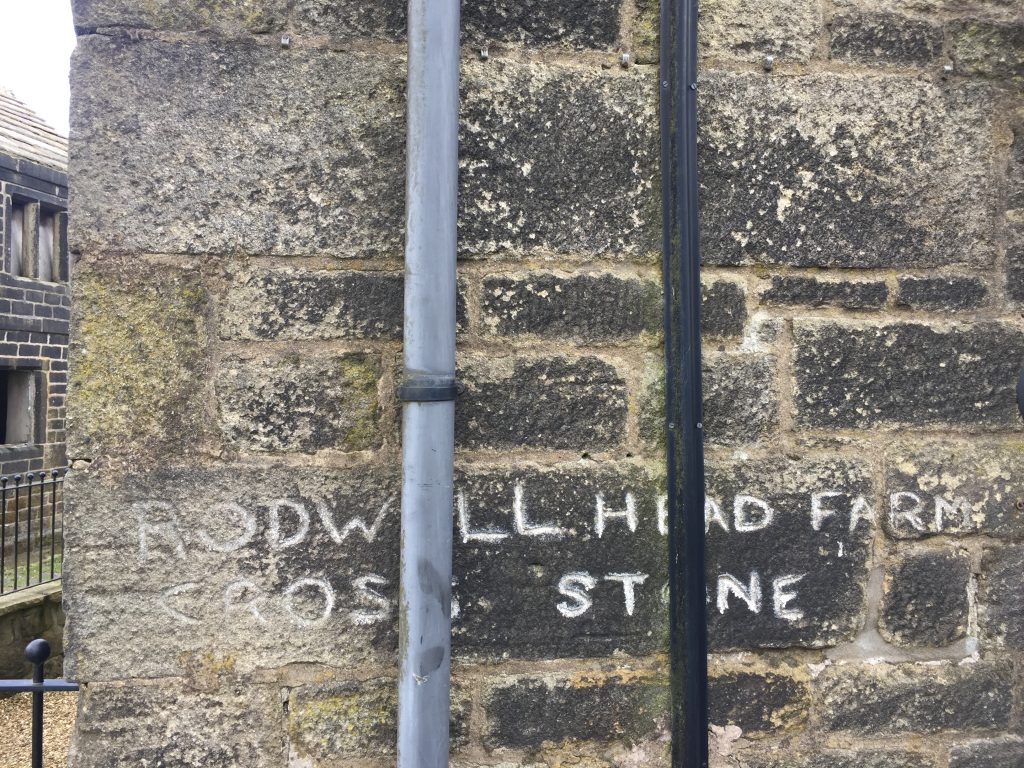

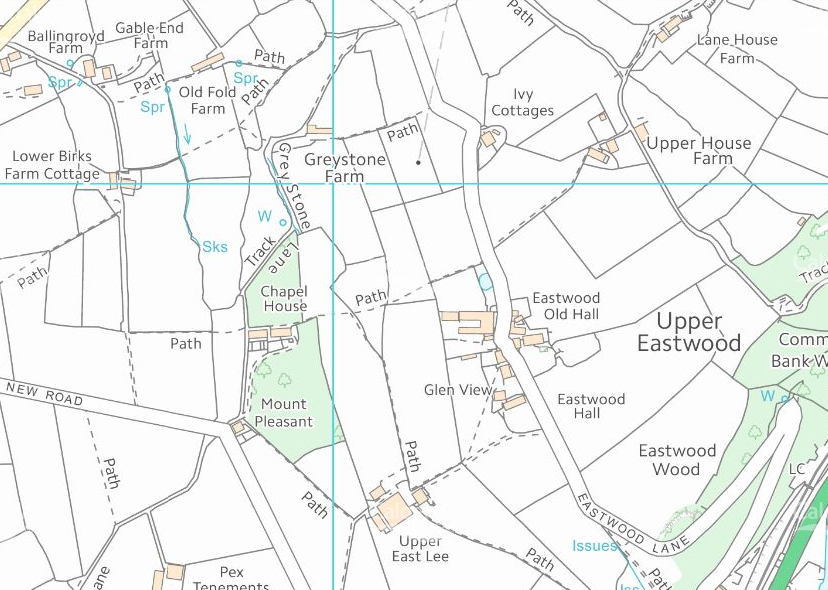

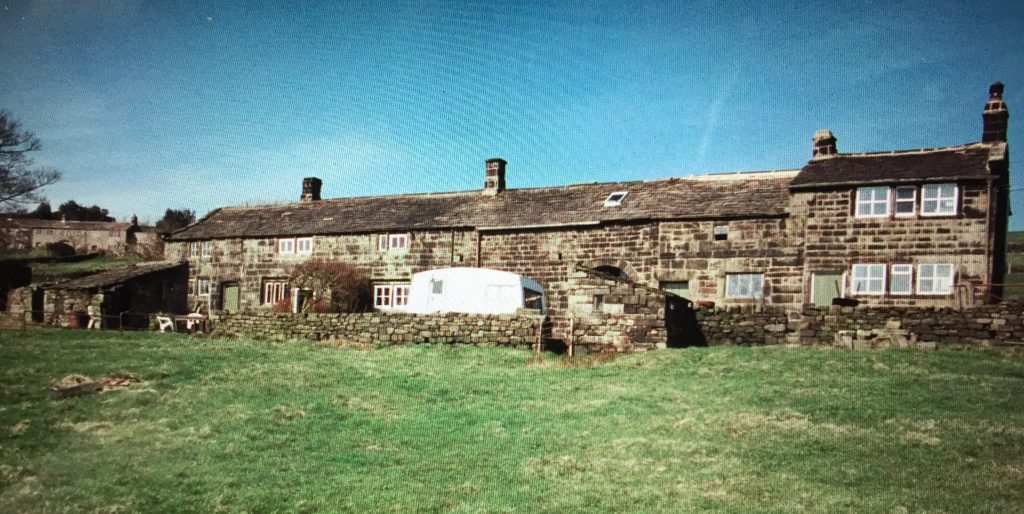

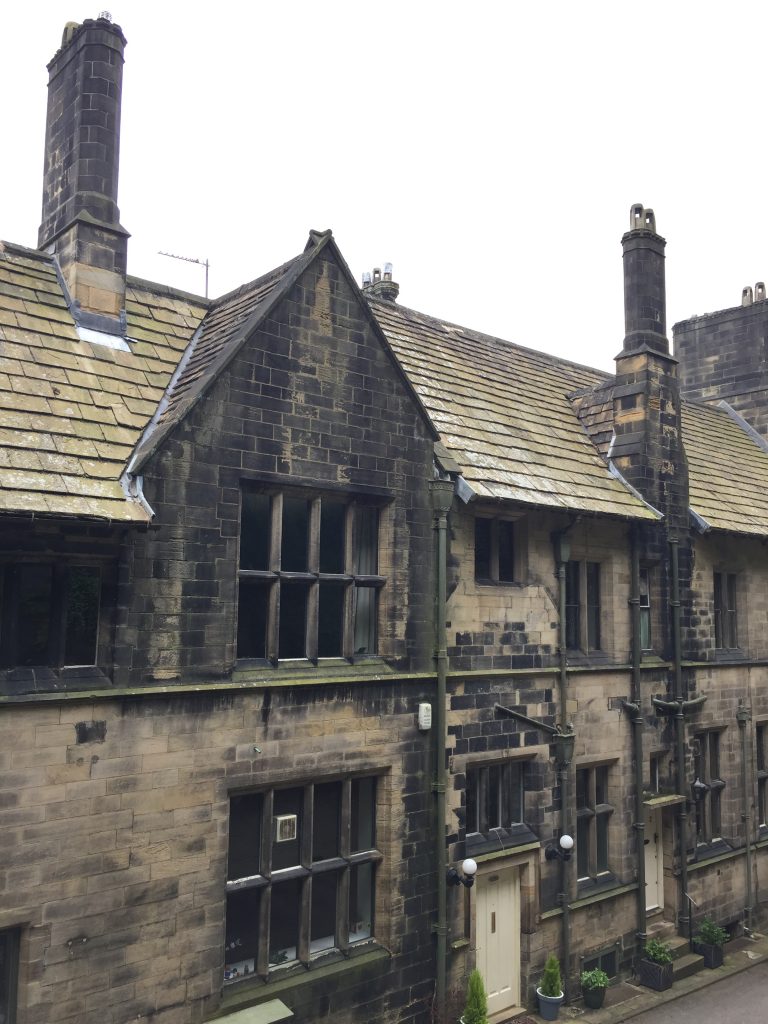

I’d sat in the front seat taking videos and photos of the white landscape stretched out before me. Then, despite the sunshine it had started to snow and the strong wind created blizzard conditions. I wondered what the weather had been like on that fateful night. Just before reaching the bridge over the delightfully named Daisy Bank Clough I turned into a well maintained cobbled side track leading to the Calderdale way and Hippins Farm. The track was walled on both sides and lined with trees reminding me of the tree lined avenue down to 3rd Bungalow, Affetside, where I grew up. Through the trees I caught my first glimpse of Ezra’s home. Today it’s is a six bedroomed property and a Grade ll listed building, a long two storey stone house set on a level area of land, a rarity in this area. All the windows are mullioned and retained their lattice glazing. The front door has an ogee lintel inscribed with I.G, 1650, and according to C. F Stell in his book ‘Vernacular Architecture in a Pennine Community,’ 1960, “is the finest 17th century yeoman farmhouse in the parish.”

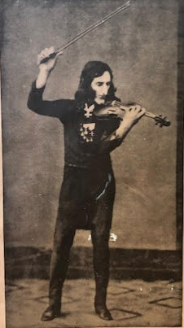

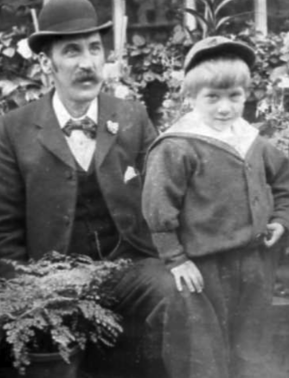

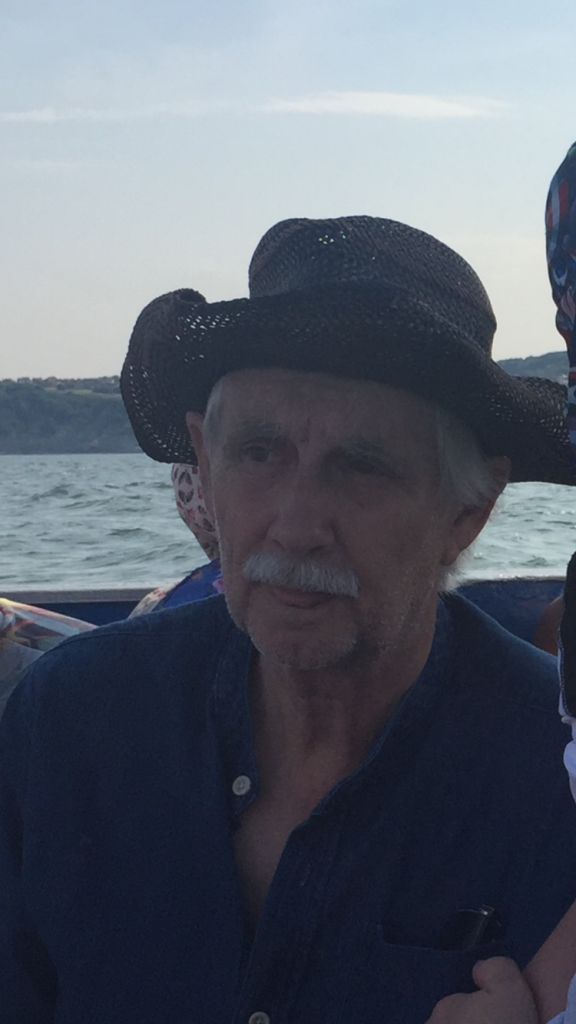

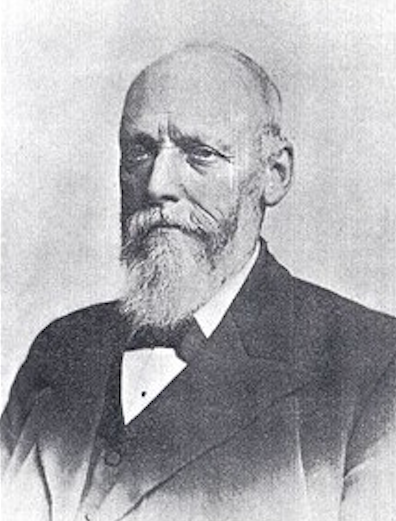

When Ezra lived there it was divided into two residences, Ezra renting one and a farmer, John William Wolfenden renting the other. Two ancient looking wooden doors complete with iron studs gave access to the property. I knocked on one of these but I didn’t get any response. I knew that the current owner has lived there for 40 years and is an avid historian. Meetings of the local history society are held at the farm. I looked in at the kitchen window realizing that it was on this very kitchen floor that Ezra was found by the postman, barely conscious, and carried to bed. Some time during the night of his drunken stupor he had fallen out of bed onto the chamber pot, breaking it in two pieces and cutting himself ‘somewhere behind.’ He stayed in bed for several days afterwards, John and his house cleaner bringing him a little food and drink, but one afternoon, possibly delirious, he took up his loaded gun from the rack in the kitchen saying “I’ll shoot ’em all.” Not surprisingly John made a quick exit. A few days later he was found by the postman lying on his back on the living room floor senseless, though still alive, undressed and ‘without his stockings’ (horror of horrors!). The postman called for help from John Wolfenden and together they got him up the stairs and in to bed. In the inquest Dr Cairns from Hebden Bridge described a four to five inch wound on the right thigh or buttock. He suggested that this, plus the exposure of being on the cold stone floor was the cause of death. Elias Barker, Ezra’s son-in-law was called as a witness. He had been immediately summoned to the farm when the postman had raised the alarm. He was asked if there was any money missing from the house, or any articles to suggest a murder robbery. No he responded. “Did you remove the chamber pot?” asked the chairman at the inquest. “Yes.” “What did it contain?” “I called it pure blood.” The court accepted that no foul play was involved and a verdict of accidental death was recorded with exposure and alcohol as contributory factors. So what led up to Ezra’s unexpected tragic end? It would seem that alcohol had played a leading role throughout his life. I was fortunate enough to make contact with a descendent of Ezra’s, one James Moss, who shared with me a handwritten copy of Ezra’s life story, as told by his daughter Grace. In it are frequent references to Ezra’s excessive drinking habits. Indeed his future wife’s brother ‘had warned her of Ezra’s drinking habits like many others associated with the railways in their early days. It was his great weakness.’ OK. That I understand. But how did this son of a ‘poor’ hand loom weaver, who became a plate layer, one of the poorest paid and least respected jobs in the railway, a gamekeeper in his spare time hobnobbing with the gentry, come to build a couple of houses in the centre of Hebden Bridge, then build the pretentious Oak Villa, send his children to fee paying private schools and then subsequently claim he has very little money and is taken to court by his own son who claimed his father owes him wages for work done? Ezra was proving an enigma to me. I was intrigued, I have a photograph of Ezra, sent to me by James Moss. He is in his middle years, standing proudly,

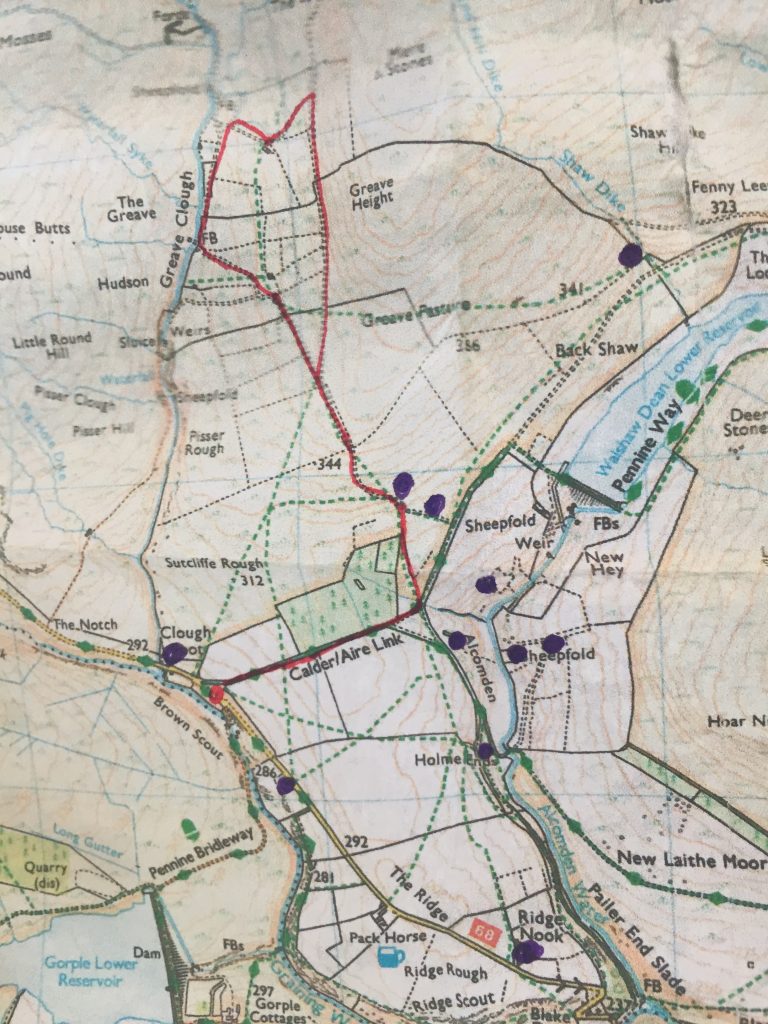

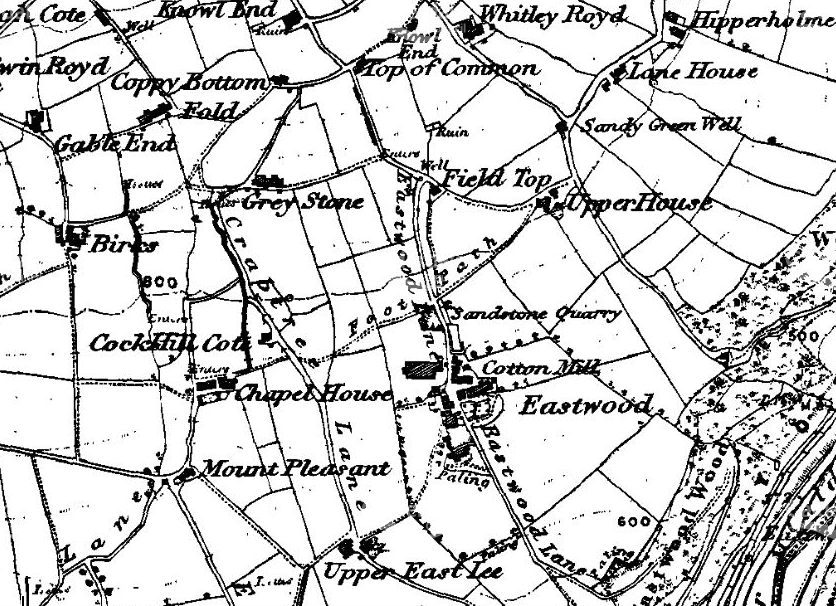

looking straight into the camera and brandishing a gun. Well, ok, it’s a hunting rifle since this is Todmorden, not the Wild West. He’s bedecked in a full gamekeepers outfit, corduroy jacket, matching waistcoat fitted nicely around the chest, white starched collar, tie, plus fours, and knee length leather boots. At his side rests his faithful hunting dog. He looks the very essence of Oliver Mellors in ‘Lady Chatterley’s Lover.’ During lockdown I read ‘The Gamekeeper’ by Barry Hines and as I began to read it on a dark wintery morning this description popped up: ‘George Purse took down his jacket from the hook on the back of the kitchen door and put it on. He took his deerstalker hat out of one of the side pockets and put that on. He was now dressed in his full gamekeeper’s uniform: hat, tweed knickerbocker suit, and woollen knew stockings. That hat and socks he had to buy for himself. The suit 30 was provided.’ How like Hines’s description was this photo of Ezra. Ezra’s daughter Grace describes his hunting experience: ‘He had the grouse shooting rights at Greave, a large sheep farm on the Walshaw Moors. The surrounding moor was owned and shot on by Lord Savile, whose shooting lodge was near by,’ Interesting! Greave had been the remote farm where one of my Shackleton ancestors had been murdered (see next chapter) and I had attended an afternoon of music in the shooting lodge last year. “Ezra was proud and fond of his well trained gun dogs. If, when shooting, a hind fell over the boundary according to law it was Savile’s and the dog was not allowed to fetch it. But invariably when, at the end of the day Ezra was comfortably settled by the fire one of his dogs, Jim would steal out in the dark on to the moors and bring in the hind. The Greave was owned by the Shackletons who, despite pressure, would never allow Savile to shoot over their land. He trained his own dogs and once, when Lord Savile borrowed Jim, the gamekeeper who returned him said ‘We will pay any price you set on this dog’ but the offer was refused. Jim had been worked so hard his paws were bleeding.” I like to think that the dog sitting by Ezra’s feet in the photograph is the self same Jim. But having shooting rights and hobnobbing with the landed gentry was a far cry from Ezra’s humble beginnings. A few days earlier I had found an online blog in which someone described his recent visit to the ruins of Dale, a lone cottage set about halfway up the hillside between Charlestown in the bottom of the Calder Valley, and Blackshawhead at the top, and which was before his marriage to Sarah Horsfall in the summer of 1856 the home of Ezra Butterworth. I’d seen references to Dale cottage in the course of my family research, knew that little if anything remains of the building, and that it looked quite difficult to get to, there being no roads and not much in the manner of footpaths still in existence. I contacted the blogger but before he could reply my curiosity got the better of me and, being blessed with a dry sunny morning, I set out in search of Dale. I had an 1851 map with me, and though the paths were marked there was no indication of how steep they are and, indeed, there’s no knowing whether they still exist today. Would I need to climb a wall, or, horror of horrors, scramble over a gate? I retraced my steps from Hippins back up to the main road and set off to reach the place of Ezra’s birth. I headed off down Marsh Lane once more to Winters, home of the Gibson family, and from there I found a diagonal track going steeply towards Dale – in fact, it was so steep and slippery with dry sandy soil that I was forced to do one of my ‘Heather specials’ as my daughters call them – sitting down and sliding down the path on my rear end. This was my modus operandi for the next half a mile or more. The view across the valley was lovely but I was too scared of losing my footing and dropping my phone to take any photos but I saw a tiny building on my left that I recognized from a photo on the Charlestown history website. It was a cludgie an outside toilet with a stream running through it. Thankfully it wasn’t too long before another path crossed mine, this time hugging the contour of the hill and there in front of me was Dale cottage – within an arm’s length. The perimeter walls of the building are still about 3 ft high and provided the perfect sitting spot for me to recover my equilibrium.

I welcomed my sit down and, after taking lots of photos, I had a picnic in what had been Ezra’s living room! The fireplace and even some stone shelving is intact.

There would have been a perfect view onto Erringden Moor in Ezra’s time, but now much of the view is obscured by trees, even on a sunny day when it’s not ‘obscured by clouds.’ Still, I could catch a glimpse of Stoodley Pike, that monument crowning the 1300ft hilltop across the valley. The tower had been erected in 1814 to commemorate the peace following the end of the Napoleonic Wars. Suddenly, on the afternoon of 8th February 1854 it collapsed. A few years earlier it had been damaged by a lightning strike,

which this is thought to have contributed to its downfall. I wondered if Ezra and other members of his family saw it fall down from this perfectly positioned viewpoint but then I realized that it would have been pitch dark by 5:30 on that February afternoon. The local newspaper recounts ‘This column was erected by public subscription in 1814, to commemorate the peace, and after weathering the storms of 40 years, it fell with a tremendous crash about half past five o’clock on the afternoon of Wednesday last, and nothing now remains but the shattered base.’ Imagine getting up one morning and finding it – gone. It must certainly have been the talk of the town. So too must have been its rebuilding which was completed two years later, the year that Ezra married. On November 10th 1855 “The last stone was put on the new Stoodley, and a handsome flag fixed therein.” I imagined the Butterworth family gathering together outside their home celebrating the completion of the 120ft monument. I have hiked to it several times from my home, climbing its dark staircase to the viewing platform, the most notable occasion with my three daughters in celebration of my birthday in 2018. It was with some trepidation that I continued my journey back down into the valley. At one point I crossed a tiny bridge over an angry torrent. It was a creepy place, reminding me of some hidden lair in a Tolkien novel, and I looked around me, half expecting to see Gollum peering at me from behind a water sprinkled rock. But it wasn’t a hobbit that caught my attention but part of a wall, barely distinguishable amidst the dense undergrowth. On further exploration the perimeter walls of an entire building was evident. A large beech tree was firmly embedded in what had once been the living room floor and bright green ferns now curtained the window openings.

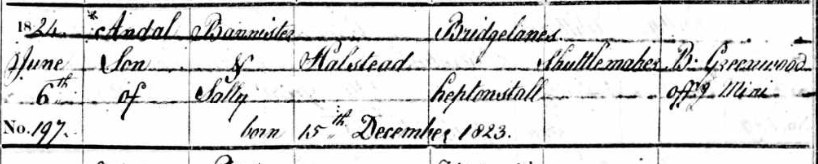

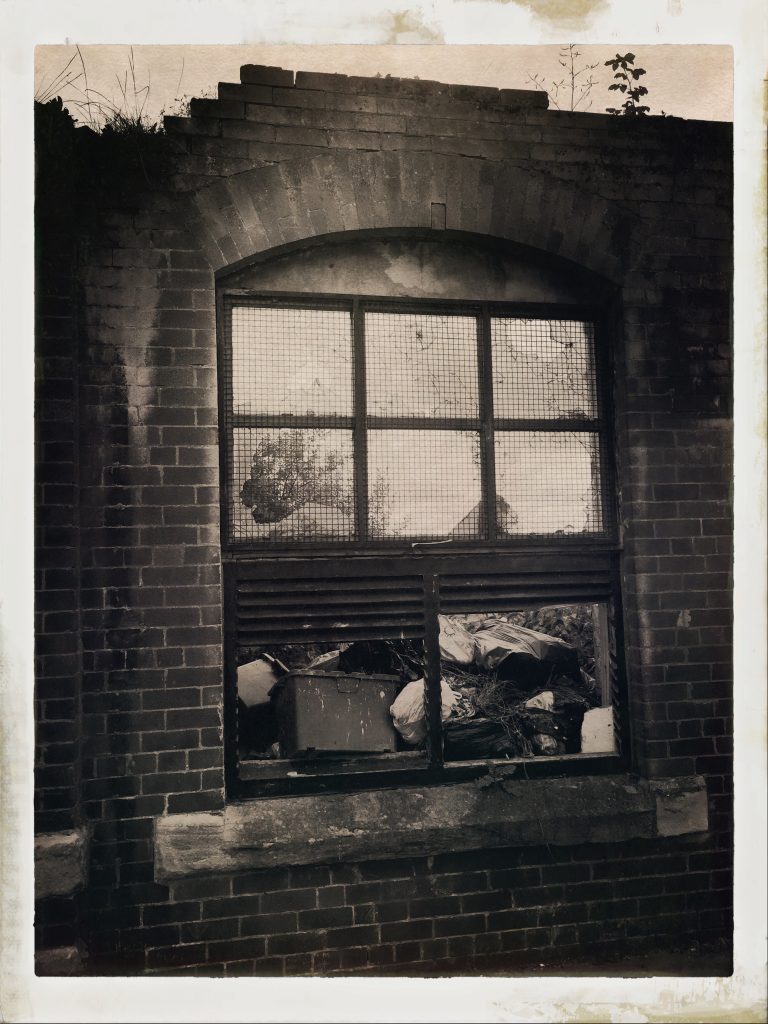

It wasn’t until I got home that I found that this was Higgin House, where, in fact, Ezra had been born – literally, in 1827. In 1841 there had been four families living here, all, apart from Ezra’s father Thomas, being involved in the manufacture of cotton, either as cotton twisters or cotton warpers. Thomas, on the other hand, was a worsted weaver as were Ezra’s older siblings of which there were four. As I approached the valley floor I found myself confronted by the railway line that shares the limited flat land of the valley bottom with the main road, the River Calder and the Rochdale canal, all crossing and recrossing each other in some elaborate weaving display. This railway line played a significant role in Ezra’s story for by his mid 20’s Ezra was a plate layer for the railways. Railways were originally known as plateways. Besides laying the track plate layers were also responsible for all aspects of track maintenance such as replacing worn out rails or rotten sleepers, packing to ensure a level track, and weeding or clearing the drains.

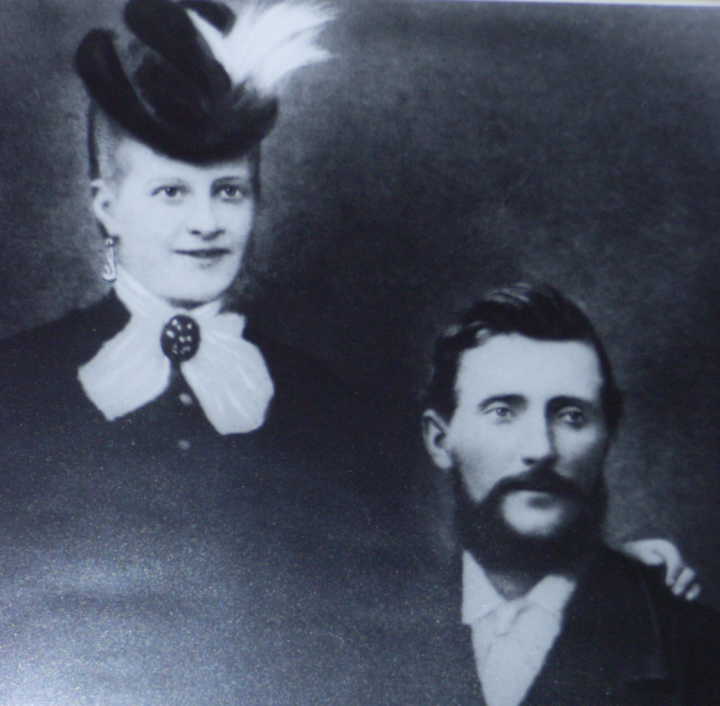

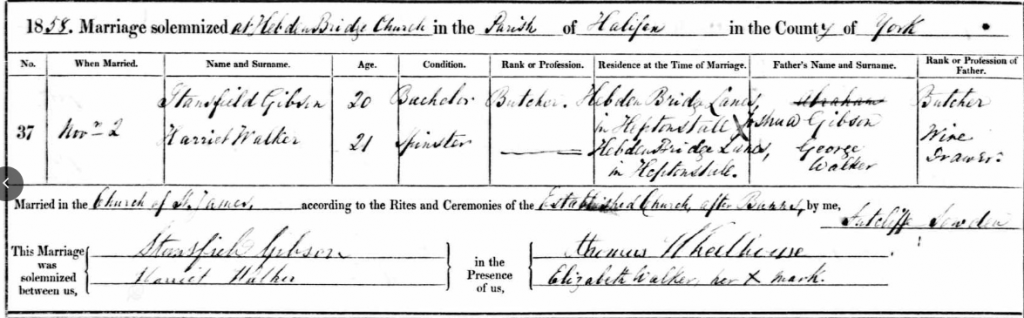

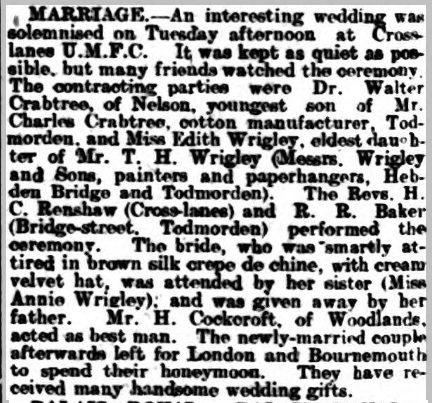

The main line from Leeds to Manchester had opened in 1841 However, Ezra’s daughter, Grace, describes his work with great pride. “he laid some lines wrongly and on being reprimanded by a superior said “But I knew they were wrong when I laid them.” “Why then did you do it?” said the man. “Because I am paid to work not think” said Ezra. “Well” replied the man, “you will be paid to think in future,” and Ezra got a rise in pay. As years went by he became a railway contractor and was responsible for the laying and upkeep of many of the lines of the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway. He was a perfectionist and the train drivers always knew when they were on his lines, they were so smooth.” Perhaps this was simply a family anecdote to be passed with pride onto the next generation. “Unfortunately his wife, Sarah, was a kleptomaniac, and was always taking home things she did not need and had not paid for. While this was a great worry to Ezra, it did not raise the problems at that time, in such a small community as Hebden Bridge then was, as it would today. Ezra just returned the goods to the understanding shopkeepers and that was the end of the matter. She died early in married life on the birth of her first child.” There was less than 6 months between his first wife dying and his marriage to Mary Gibson, daughter of the Joshua Gibson, innkeeper of the Bull Inn, Hebden Bridge. They started married life at Weasel Hall, a large building set alone above Hebden Bridge and which I have a perfect view of from my writing desk. It’s lone position at that particular height above the valley always reminds me of the position of Lily Hall over the Hebden valley, and when I chatted to the current resident of Weasel Hall I was not surprised to learn that the two halls had been renovated by the same contractor in the 1980’s.

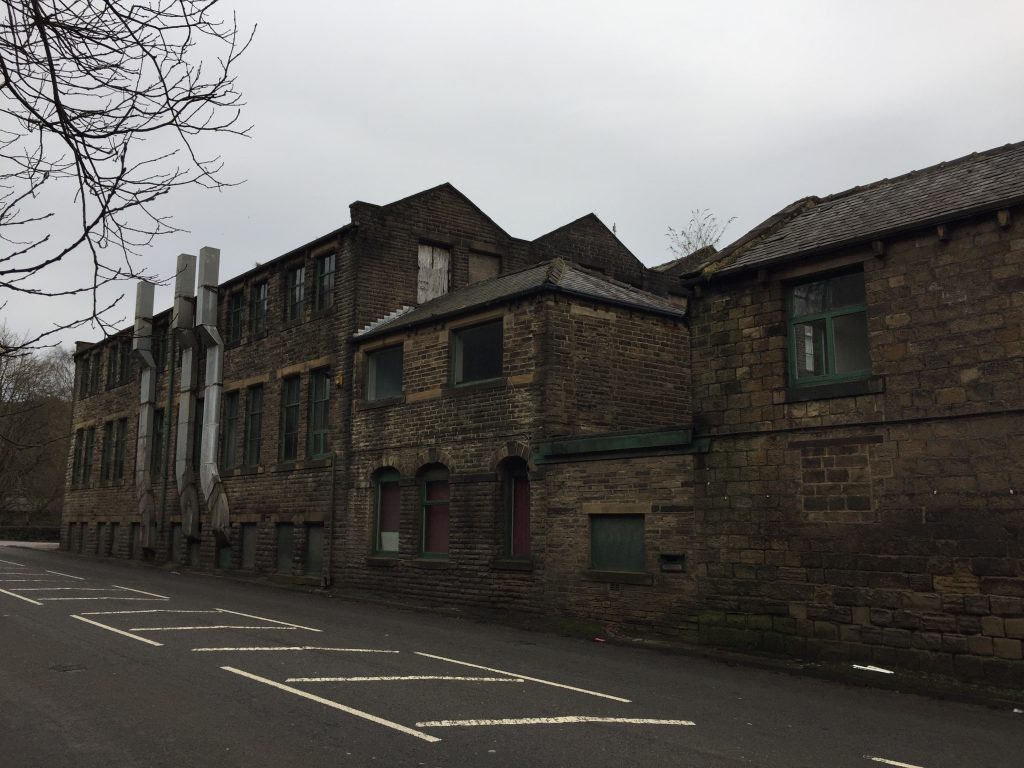

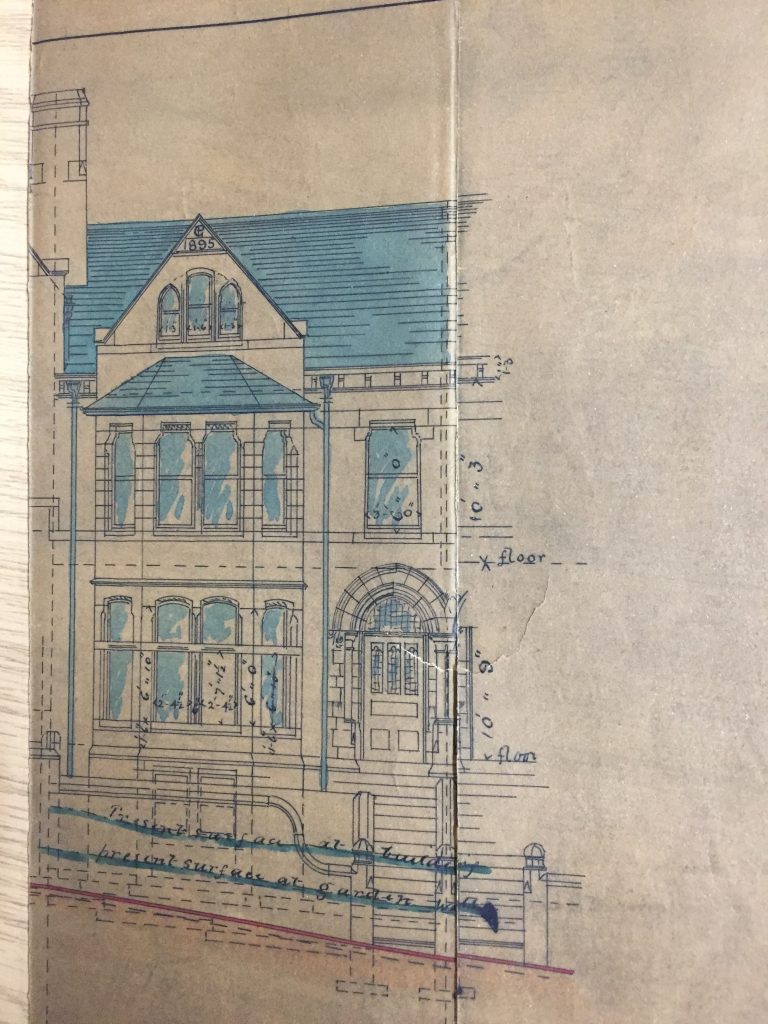

For a couple of miles I followed the path alongside the railway track back towards Hebden Bridge, bound for Oak Villa, the gentleman’s residence that Ezra had built for himself and his family. By this time Ezra and Mary had two children, Grace and Gibson. So far so good. It’s the next portion of Ezra’s story that I find puzzling. According to Grace’s account “In due course they moved to Commercial Street and then to Carlton Terrace where Ezra had built some houses on the present site of the Cooperative building,” Yes, Ezra had become a railway contractor, perhaps implying more of a supervisor’s role but where did he find the money to build ‘some houses.’? And to top it in 1875 Ezra decided to build a house in Savile Road. Several detached houses were being built there at that time and he bought a piece of land along the ledge and built Oak House, and another house just next door but which he fitted as a stable, but which he planned could be converted into a house.

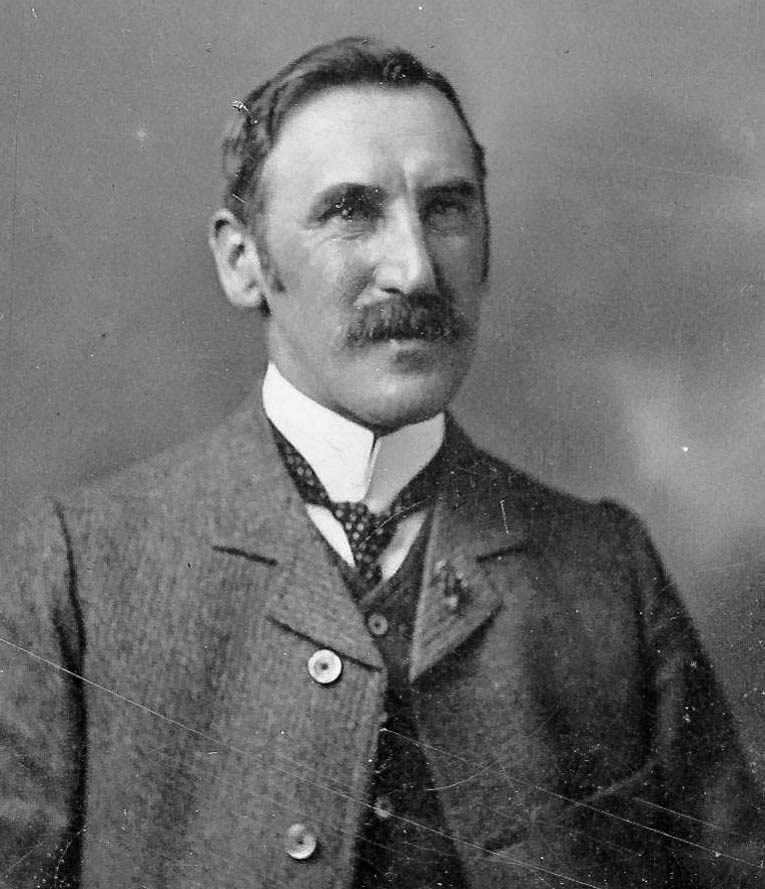

Next to that he built Oak cottage where lived his gardener cum groom and beyond was a long stretch of kitchen garden. His ‘gardener cum groom’? He was living the life of a 33 gentleman! In the 1881 census he describes himself as a farmer with 9 acres. ‘He was always a man ahead of his time, and Grace never remembered living as a child in a house without a bathroom.’ As I stood opposite Oak Villa my mind spread its own rumours about how Ezra could have come by enough money to build these three gentlemen’s residences that reek of Victorian opulence – asymmetrical design, an abundance of windows, an elegant bay window in the sitting room, a steeply pitched rood topped with blue slate. Could it be significant that Oak Villa lies on Savile Road, named after the wealthy landowner whose lands were adjacent to Greave and for whom Ezra was the gamekeeper? My mind returned to Grace’s story – “ and once when Lord Savile borrowed Jim the gamekeeper who returned him said “We will pay any price you set on this dog” but the offer was refused.” I don’t suppose we shall ever know and his Moss descendants are as puzzled as I am. At the time that he built Oak Villa he was in his early 50s with a wife and two children in their late teens. I took it for granted that Ezra intended to live in this luxurious home for the rest of his life, enjoying the benefits it offered. But that was not to be. In 1890 Ezra decided against the wishes of Mary and Grace to lease Hippins farm from the Savile estate, paying an advanced payment that would secure his tenancy for the next 25 years. Correspondence between Ezra and the Savile estate shows that Ezra was paying rent of 6s. and 11d for Hippins, a 75 acre farm, with the house being subdivided with the Wolfenden family, John Wolfenden to help with the farm and his wife is act as a general servant. He spent a great deal of money on improvements building a new barn and reconstructing much of the interior of the house. He bought from Ireland twelve Kerry cows and a bull and settled down to a very different way of life. It was eight years later that his tragic death occurred. His will shows that he never patched up his feud with his son Gibson, omitting him from his will. It’s less easy to understand why Ezra left money to Grace’s husband, Elias Barker, a prominent cotton manufacturer in Todmorden, and not to Grace herself, but perhaps that was just indicative of the place of women in society at the time. From Oak Villa it was only a few minutes walk to St James’s cemetery, Ezra’s final resting place, where he was buried on Christmas Eve, 1898. His wife, Mary, outlived him by 20 years and is buried alongside him.

Recent Comments