It all began with one man and his dog. The man, Edward, was a shepherd. I didn’t catch the name of his sheepdog but she was having a jolly old time swimming around in an old bath tub in the sheep field as I chatted to her master. I was on Edge Lane, between Heptonstall and Colden, and had just arrived at Spink House where my ancestor Giles Sunderland was living in 1891. As I paused to take photos of the building Edward came into view. I thought perhaps he lived there, but no. He was just walking along the tack to his sheep field. We chatted for a while and as we parted he said, “If you are interested in history make sure you find out about Raistrick Greave.”

Edward . . . . .

. . . .and his sheepdog

Hmm. . . A couple of days later, quite by chance I found a video of someone’s hike to the ruins of Raistrick Greave, a farmhouse in a very isolated spot way up on Heptonstall Moor above Widdop. Its name reminded me of Greave farm where Gibson Butterworth was living in 1901 so I decided to do a bit more digging online. With 20 or more ‘hints’ on the Ancestry website, Gibson looked like a ‘person of interest.’

Until a couple of days ago Gibson Butterworth was just another name on my Nutton family tree, one of over 2000 names. I knew he and his sister Grace had been born at Weasel Hall, a building high on the hillside that dominates the view from my desk where I write this.

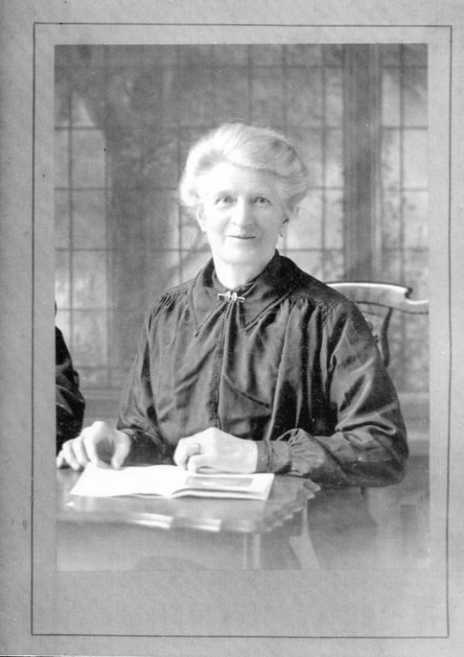

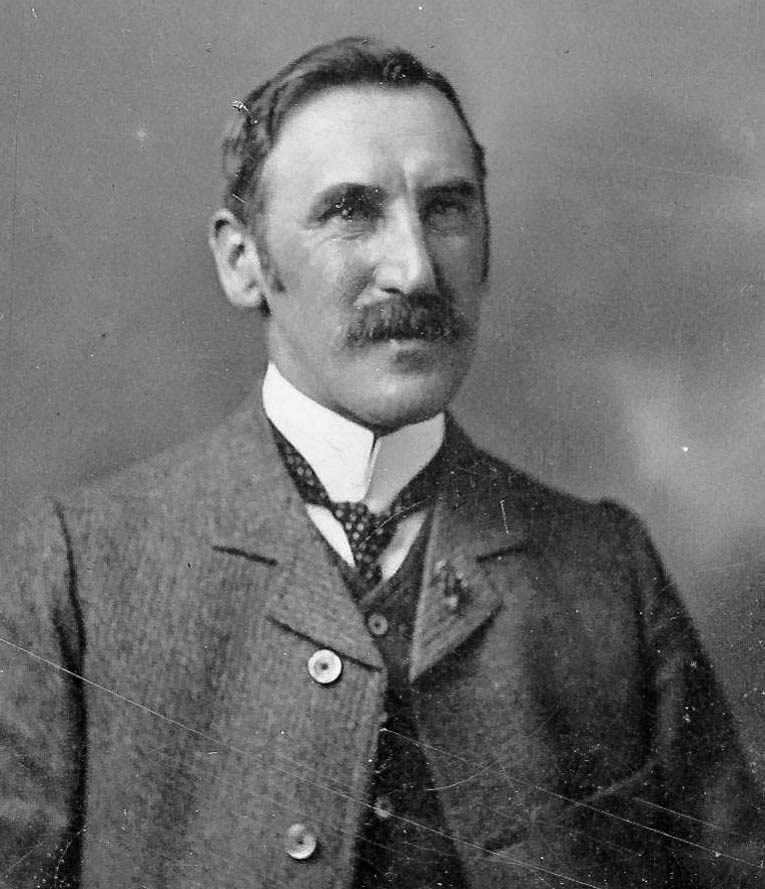

A few months ago I’d been given the handwritten account of the life of his father Ezra Butterworth, along with some wonderful photos from James Moss, someone on Ancestry.com whose family had also married into the Butterworths.

GIBSON BUTTERWORTH

The son of Ezra Butterworth and Mary, (nee Gibson) he was assigned his mother’s maiden name as his forename, a very common occurrence in these parts. Indeed my dad’s middle name was Dean, in memory of a family surname. Gibson was born in 1863, the same year that Cheetham House sewing factory in Hebden Bridge was built. I’d lived there for the first 18 months after my return to England, in an upper room where huge iron wheels from the pulleys that powered the machines still graced my ceiling.

My previous home in the old sewing factory . . .

. . . . with pulleys in the ceiling

According to the journal that Grace kept “Gibson was a great disappointment to Ezra. He was highly intelligent but perhaps in- herited too much of his mother’s temperament. He was educated first at Heptonstall Grammar school and later went as a boarder to a school at East Keswick. Though he wanted to be an engineer he never seemed to settle down. Ezra started him in the clothing business in Hebden Bridge but after two years he threw it over in disgust and became a wanderer. After forty years he retuned from New Zealand and settled in a cottage in Hebden Bridge. Even in his old age he was a very gifted speaker and would draw people to his cottage just to listen to him.He and Grace seemed to have been very close to one another but while Grace accepted her mother’s domination Gibson would not. So there grew a fierce hatred between Mother and Son which lasted as long as they lived.Maybe that was the cause of his differences with his father.

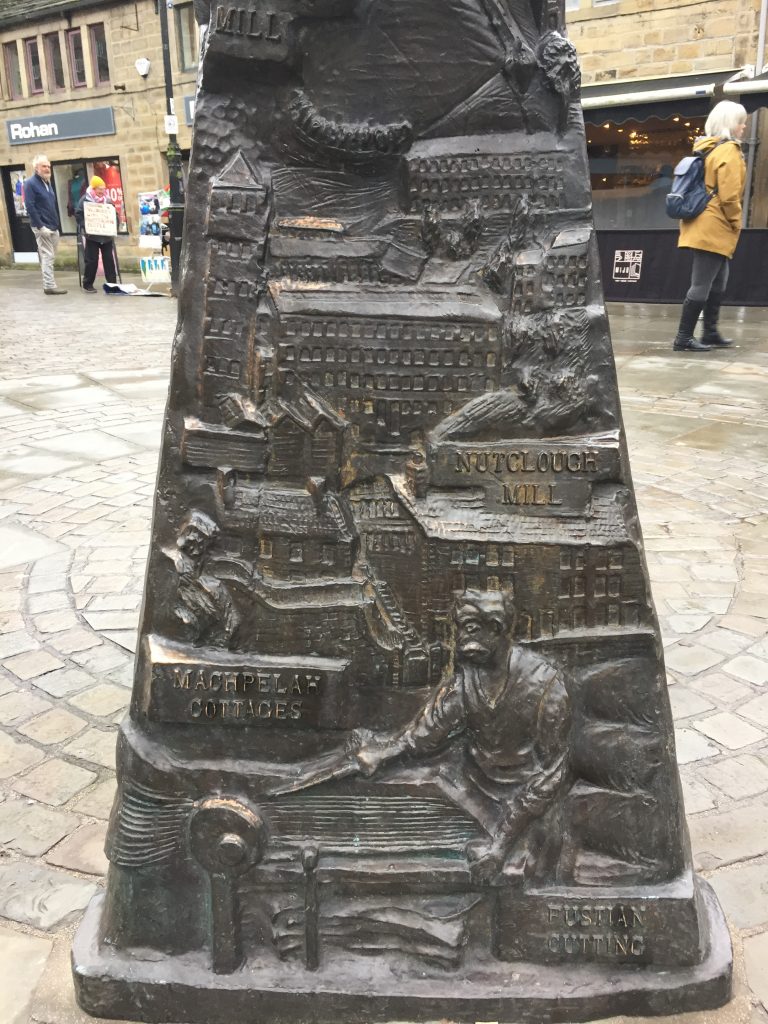

Gibson was educated in Heptonstall grammar school, that fascinating building which first opened its doors in 1642, the year before that the town was directly involved in the Civil War, when the battle of Heptonstall took place in the remote hilltop community. The parliamentarians of Heptonstall did battle with the Royalists of Halifax. In 1871 Gibson was a young 8 year old, living on Crown street (my current address) with his family. His dad, Ezra was a railway contractor held in quite esteem according to the written account of his life. “He was responsible for the laying and upkeep of many of the lines of the Lancs and Yorks Railway. He was a perfectionist and the train drivers always knew when they were on his lines, they were so smooth.” So recounted his daughter, Grace. I’ve been trying for 2 years to work out which buildings various branches of my family lived on Crown Street, but to no avail. By 1881 Gibson’s family appear to have moved up in the world judging by the fact that they are now living at Oak Villa,a house built especially for the Butterworths and Ezra is a farmer with 9 acres. See my blog about Ezra. http://blog.hmcreativelady.com/?s=ezra

In 1890 his Ezra his wife, Mary, and daughter Grace had moved to Hippins farm, which Ezra leased from Lord Savile’s estate. It was a 75 acre farm set high on the hill top above Todmorden . In the 1891 census Gibson is still at Oak Villa where he is living with his Uncle, Thomas Butterworth, another plate layer for the railway and his wife Mary Ann. This in itself is perhaps insignificant but new paper reports fill in the back story of a major rift in the family. Indeed, the newspaper article is entitled: Unhappy Family Differences – painful disclosures. Ezra had deleted Gibson from his will and so Gibson was claiming financial compensation by taking his mother and sister’s husband, Elias Barker, to court to claim what he believed was owing to him. The court decided on a nominal sum.

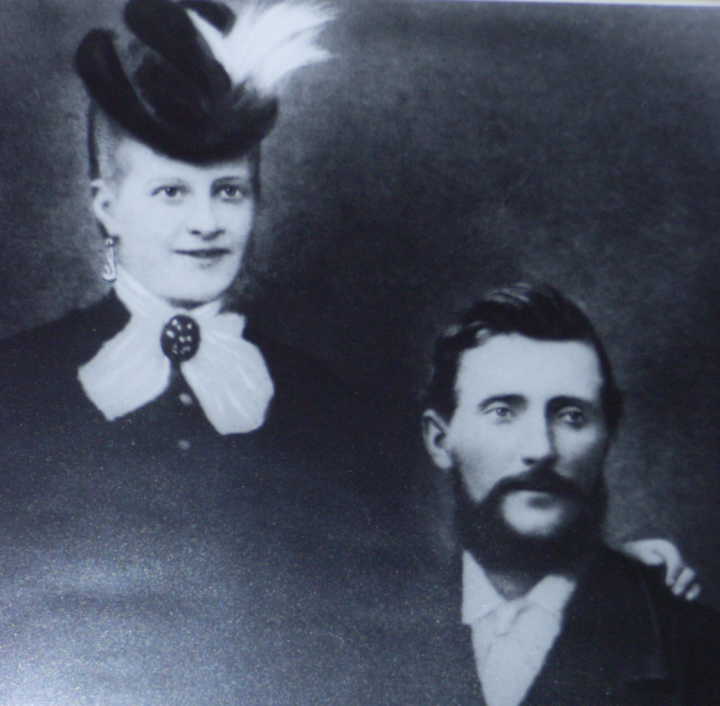

Sharing Hippins farm in 1891 was the Wolfenden family, John William Wolfenden, his wife Jane, and three young children, one of whom was named Isabella, aged 3, so born in 1888. There just HAD to be a connection, since Gibson had married an Isabella Wolfenden, born in 1857. It took me into the early hours of the next day before I’d cracked it. John William was Isabella’s brother. And just to complicate matters still further John William Wolfenden’s wife’s Jane was a Butterworth, Jane Butterworth, born in 1856! I guess the families living in the remote hilltop farms would gather together and mingle and perhaps meet their future spouses at stock sales and other farm related activities.

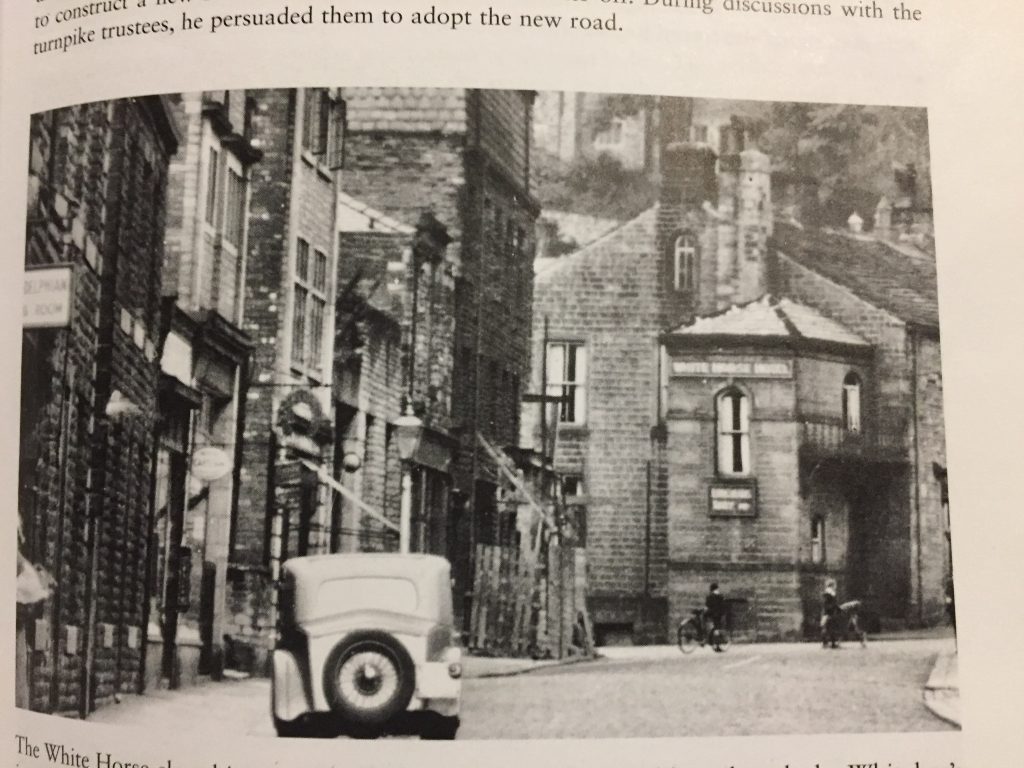

Two years after Ezra died 1898, a tragic death, caused by an injury sustained by falling onto his chamber pot in a drunken stupor, Gibson married Isabella Wolfenden, a second marriage for the widowed bride. The marriage took place at Slack Chapel. The present building was constructed in 1879, replacing the earlier building of 1808 where the opening ceremony was attended by seven hundred people. More than a thousand were at the Dedication service on the following Sunday.

It’s no longer a chapel but when I’d visited it in the August 2017 it appeared that some building or renovation work was in progress. I’d even chatted to a man that came out of the building to find out what I was doing. But three years later the place looks in the same unfinished condition. In July 2015 a picnic was planned on Popples Common to discuss the building’s future. Plans for it to become a halfway house for those recovering from drug abuse were dropped after objections from local residents. I chatted to the current owner, Holly, as she tended the gravestones that make up her front garden. “You can’t live here if you have a nervous disposition” she quipped. So now let’s find out more about Gibson’s wife.

ISABELLA WOLFENDEN

Isabella was from Paythorne, a picturesque village on the River Ribble, in the Forest of Bowland, and her dad, John, was an agricultural labourer. By the time Isabella was 10 years old the family had moved to Good Greave, a farm on Heptonstall Moor, a farm that has been in the Shackleton family for a long time. I mean, a really long time! In the 1604 survey out of 26 farmsteads in Wadsworth 14 were owned by Shackletons and the document specifically mentions 2 at Good Greave. There was a Richard ‘elder’ and Richard ‘younger’ at Good Greave in the Court Roll of 1603 and in documents of 1605 but not on the Savile tenants lists as ‘they’ had bought their farm in 1600.

A more remote spot on the moorland is hard to find. Indeed, it took me a while to be able to pinpoint the exact location of Good Greave on a map. I enlisted the help of various Facebook pages and although I had several responses it was still proving difficult to find the location so Greave and Good Greave, both of which are now in ruins, with nothing but ill-defined tracks through the peat bog. One photo purporting to be of Good Greave shows a stone doorway and lintel, all that survives of this remote farm.

Isabella was one of 5 children and the oldest daughter. Her 3 younger siblings had been born in Barnoldswick. Up on the moors living next door, if such it can be called, at Greave, was Thomas Shackleton, a farmer aged 28 , living with his widowed aunt, Jane Uttley aged 67, a retired farmer, and his sister Sarah Ann and two servants. On December 14, 1873 the 16 year old Isabella married the 31 year old Thomas Shackleton at Halifax minster and Isabella moved to Greave to live with her new husband .

Questions floated around in my head. Where did the Shackletons buy food? Would Isabella have had another woman to help her in childbirth? They were 4 miles from Heptonstall amidst some of the most barren and windswept places in Yorkshire. But the Shackletons appeared to flourish.10 months after their wedding James was born, to be followed by 6 more children, approximately every 2 years. Two died within their first year and one, James, the firstborn when he was 7.

JOHN WOLFENDEN

But what happened to Isabella’s father after his daughter married and moved out? Some time between Isabella’s marriage in 1873 and the 1881 census John Wolfenden had taken over as landlord of the Ridge inn on Widdop Road, now known as the Pack Horse. It claims to be the highest and most isolated pub in the Upper Calder Valley and in January 2004, the pub won the National Civic Pride gold standard award, as the most scenic pub in Britain, beating 200 other pubs.

From the Hebden Bridge Newsletter, 29 July, 1881

“IRISH LAWLESSNESS AT WIDDOP. EXTRAORDINARY SCENES. on Wednesday last a report spread rapidly throughout the district that in an Irish affray at Ridge, Alcomden one or more lives had been sacrificed , and in Hebden Bridge particularly the rumour caused some uneasiness and dismay. Happily, as it turned out there was no fatality, but conduct of a most extraordinary character took place at the place named, which, but for the discreet conduct of the police, might readily have led to serious and possibly fatal consequences. It appears from all we can gather, that on the afternoon of the preceding day, two young Irish mowers, John Devine and Patrick Fox, went to the Pack Horse lnn, Ridge, now kept by Mr. Wolfenden, (Isabella’s dad) and them began is create a disturbance. An Englishmen who was present managed to overcome them, and into the bargain gave them ” a good hiding” (to use a local expression).

Next morning the two returned to the inn along with a number of their fellow-countrymen, and it is presumed they came hoping to find the Englishman and to have their revenge upon him for his victory of the previous day. He was not there, however, and the gang at once began to abuse and insult the landlord and his family. Eventually they turned Mr. and Mrs. Wolfenden, and their daughters, (these would be Mary Ellen, 13, and Annie Jane, 9) out of the house and having become for the time masters of the situation, made use of their opportunity to feast and be merry at the expense of someone else. They helped themselves it is said, to the estables which were in the house, also to the beer, spirits and cigars, and to give greater variety to their enjoyment began to break glasses, windows etc. During these orgies one of the men, as we are informed, took off all his clothes except the fragments of a shirt which he was wearing, and in that condition went outside and exposed himself to the female members of Mr Wolfenden’s household. Fox and Devine were the ringleaders in the affair, and as soon as the attendance of the police could be obtained – which was not until afternoon as the inn is about 5 miles from Hebden Bridge, (on horseback) these two were given into the custody of P.C.s Shaw and Slee who had been sent to the scene. The charges on which they were taken into custody were for refusing to quit and willful damage. The prisoners were handcuffed together and conducted towards Hebden Bridge by the officers followed for a time at a distance by seven men who had taken part in the affair. (So the procession begins the 5 mile trek back to Hebden police station).

At Blakedean the officers and their prisoners were overtaken and the gang began to threaten the officers what they would do if they did not liberate the two prisoners.

There was some struggling and shoving about and one of the men took up a top-stone from a wall (I see the wall on the photo) and threatened to knock P.C Shaw’s brains out if he did not loose the handcuffs and set Devine and Fox free. Seeing, at last, that they would be overpowered and that there was no chance to land their prisoners safely at Hebden Bridge, the officers let the prisoners go, but carefully noted the direction which the gang took with a view of following them when they had obtained further assistance. Shaw and Slee made haste to Hebden Bridge while the gang made in the direction of Colden. About quarter to six P.C’s Shaw and Slee along with P. C Eastwood, P.C’s Norton and Taylor and two civilians set off to try to find the men. At Popples, Heptonstall, the officers separated into two companies, Slee going in one direction and Shaw with the other.

Shaw’s section went first to Longtail beerhouse, (this is on Edge lane and is now terraced cottages) tolerably confident of finding some of the men there, but were disappointed. They learnt however, that some of the men had passed the house previously going towards Colden. The officers then made in that direction and at Old Smithy or Hudson Lane met 4 of the party including Devine and Fox. The other two were Samuel Easterbrook and Thomas Castle and were apprehended on a charge of assisting to procure the rescue of Fox and Devine. Castle made an attempt to escape but was run down and caught. The four men were handcuffed together and led off to the police station at Hebden Bridge. Their arrival created unusual attention as at that time rumours of a murder having been committed were still current. some of the prisoners were bruised and disfigured about their faces and all acted with considerable bravado as they marched through the streets. One of them, it is said, was the ringleader in a row which took place at Bridge-gate on Sunday week. The rest of the gang were not captured. The 4 prisoners were brought up yesterday morning at West riding Court, Halifax before Capt Rothwell and Dr Alexander. Devine and Fox pleaded guilty to a charge of being drunk and disorderly on the previous day. . .The men were strangers. They had left their native country being afraid of the Coersion Act. (an act of parliament which allowed the internment without trial for anyone suspected of involvement with the Land War, whereby tenant farmers would gain a fair rent and fixity of tenure) .Fox had left Ireland 8 years before, and Devine 5 years before. The bench imposed upon each prisoner a penalty of 10s and 14s 2d costs with the alternative of 14 days in prison. Easterbrook and Castle were ordered to pay one pound and 14s 2d costs or go to Wakefield for one month with hard labour.”

June 15, 1883 DEAD body found in Widdop reservoir – Queer feelings in Hebden Bridge.

The water bailiff found a dead body floating in Widdop reservoir. The body belonged to a man aged around 55 and his coat, cap and scarf had been neatly laid on the bank. Judging from the fragments of newspaper in his coat pocket it was surmised that the dead man had come from Burnley, and that he had been taking a wash when he fell, possibly seized with a fit, rather than having deliberately taken his own life, because, the inquest reasoned, he would not have place his clothes so neatly. A boat was taken onto the reservoir and the dead man was taken by cart to the Pack Horse, Widdop to await identification and inquest.

Millstone grit outcrops

Visit with Sarah, May 2018

Some Folk in Hebden Bridge immediately began to revert to using well water believing that their running water would have been contaminated by the body, which, judging by its condition, had been in the water for a considerable time. Other stories abounded included people imagining they had seen” bits of toe nails” coming down their pipes. The inquest took place at the house of Mr John Wolfenden at the Packhorse Inn, Ridge. The jurymen viewed the body and then listened to the evidence. By chance a friend of the deceased’s wife saw a newspaper article about the discovery of a body in Widdop reservoir. He knew that his friend’s husband, Mrs William Whitehead had been missing from home and so they made arrangements to come to hebden Bridge. Apparently they missed the train and had to take a pony trap over the hills from Burnley and arrived at the police station in hebden bridge just as the police officer was returning from The Pack Horse with the clothing recovered at the scene. Mrs Whitehead immedaitely identified them as belonging to her husband. He had been missing from home for three weeks and “had been in a desponding state of mind for some time. Five years before he had attempted suicide by cutting his throat.” An open verdict was returned. After the inquest what must have been a very badly deteriorated body was placed in a coffin and transported to Heptonstall for burial but due to some misunderstanding no grave had been prepared for the burial. “The man in charge of the hearse was in a bit of a quandary but eventually he was allowed to deposit his freight in the church porch.’ From where the deceased’s wife collected it around midnight, placed it in a hearse and took it to Burnley at 7:30 the following morning.

My artwork of the rocks

Photo of interesting rocks at the reservoir

Isabella’s father, John Wolfenden, died at the Pack Horse Inn Widdop on January 27, 1886 .

Four years later on May 16, 1890 Isabella’s husband, Thomas, died at the age of 58. He was buried at Blakedean Chapel the following day, which seems rather unusual. The headstone now lies prostrate on the grass. I visited the spot on June 15, 2020, two days after a tremendous thunderstorm in which there was a reported tornado only a couple of miles from this very spot.

At first I couldn’t find the grave but at last I saw a grave stone holding water and could read that this was the family grave where Thomas and his sons, John, James, Robert Kay and Richard William Foster were laid to rest. What a wonderfully tranquil place. I tried to figure out where the chapel had been. It was built in 1820 as an offshoot of Slack Baptist chapel. All that remains now is the Sunday School which was used as a scouting retreat after the church closed in 1959. My mind raced. Where did the people come from to worship here? Because of the lie of the land being so steep the gallery was accessed by steps from the road above. At the time of her husband’s death Isabelle’s youngest child was 8 months old and now, at the age of just 32 she was already a widow. The census of the following year shows Isabella as the head of household and a farmer. Her oldest son, Richard, aged 14 is the ‘farmer’s assistant.’ Her other children are aged 6, 3, 1 other children and her 52 year old sister-in -law is an assistant housekeeper and another Shackleton lady relative, aged 50, is ‘living here own means.’ Both these ladies had both been born at Good Greave.

It took 10 years for Isabella to remarry, and that’s when she becomes part of my family’s story marrying Gibson Butterworth at Slack Chapel on March 27, 1900. Isabella was nine years older than Gibson. How did they meet? OK. It took my a couple of hours to figure it out but Glory Be! I figured out how they met! In 1891 when Ezra Butterworth, Gibson’s dad was living at Hippins he was sharing the large house with John William Wolfenden who, it transpires was none other than Isabelle’s brother.

By the 1911 census the family are living in Nelson – just over Hepstonstall Moor from Good Greave, and Gibson is a . . .builder of canal boats. Wow. That was unexpected! From the middle of a moor in one of the most remote parts of England and he becomes a canal boat builder. This is so funny. Yesterday I was in Heptonstall and I was taking another look at the sign in a back street that’s falling apart. It says Boats for Rent. An ‘old timer’ saw me looking and I struck up a conversation. “Boats for hire? Heptonstall is on top of a hill! Where could you sail a boat?” I asked. “Well now. There are reservoirs around here, Gorple, Widdop, Walshaw,” came his response.

As we chatted further it turned out that he knew the dentist that had his office in my living room – Donaldson was his name. That’s the second person I’ve met who remembers my apartment being a dentist’s office. The first was a lady in her 90’s at the Mytholmroyd Community Christmas in 2018. This man in Heptonstall was proud to tell me he is in his 80s. Gibson appears to be a boat builder and working for his son-in-law, Thomas Whitaker from Barnoldswick who is an employer of canal boat builders. How interesting! Isabella died at Moor Lodge, Oakworth near Keighley but is buried at Blakedean. Today it’s a country retreat and from 2003 to 2015 it held international sheepdog trials raising almost 30,000 pounds for the air ambulance.

After Isabella died Gibson had planned to emigrated to New Zealand. He boarded the ship called the Shropshire at Liverpool, part of the Federal Line. He was 56 and planned to be a farm hand and was bound for Auckland. 25th Feb 1921. However, he arrived back in England, at London from Wellington 30 Nov 1922 on the Corinthic, part of the Shaw, Savill and Albion Company Ltd. He is 57 describes himself as a carpenter.

Recent Comments