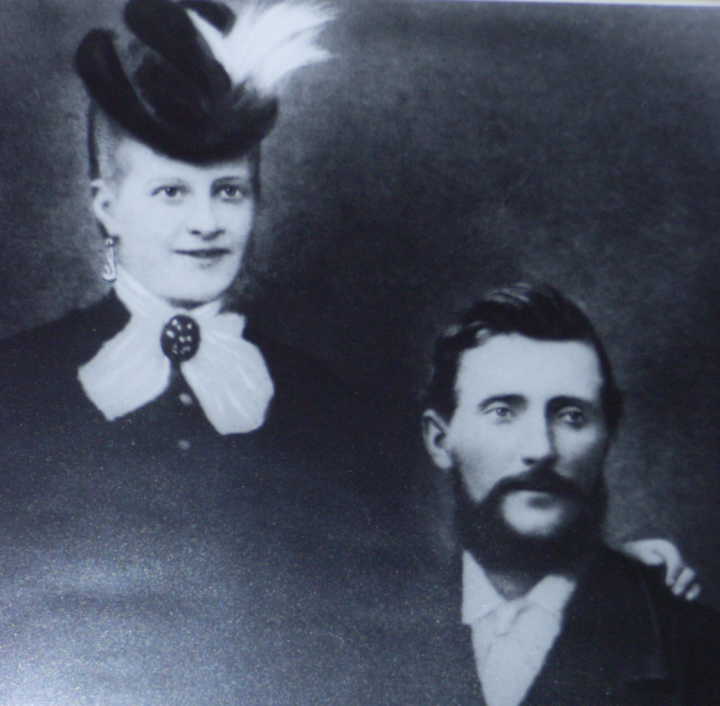

At his baptism on March 18, 1865, Ezra and Mary’s son was given the name Gibson, the surname of his mother. The church of St James, in Hebden Bridge must have been crowded since Gibson was one of 11 children baptised that day by Rev George Sowden. In 1900, at the age of 36 Gibson Butterworth was to become the second husband of Isabella Wolfenden, a lady born in 1857 in Paythorne, a small village in the Ribble Valley, Lancashire, 15 miles north of Burnley. Isabella’s father was an agricultural labourer, supporting his wife Hannah and their five children and by the time Isabella was ten years old the family had moved to the remote moorland dividing Lancashire and Yorkshire where her father operated Good Greave farm.

Just across a field from Good Greave was Greave, where Thomas Shackleton, a farmer, was living with his unmarried sister, an elderly aunt and two servants. It’s little wonder that in this sparsely populated area the two families got to know each other well and at the age of 17 Isabella married the 28 year old Thomas, the man who lived next door – well, just across the field. Isabella’s brother was the same John William Wolfenden who had been living next door to Ezra Butterworth at Hippins and had cared for him after his fatal fall. In 1827, 40 years before Isabella and Thomas sealed their marital knot, Thomas’s farm had been the scene of a horrific murder that made headlines in newspapers all across the country. A policeman was even sent from London to attempt to solve the gruesome crime on this lonely moor. The victim was Thomas’s great great uncle, James Shackleton. This area already had its reputation as a God-forsaken place. “Our moors put you in fear o’being stabbed in the back! We are without cultivation except for kicking one another to death in clog fights o’ the long dark winter nights. This is a godless place, dark and inhospitable.” So comments Mary Lockwood in the fictionalized account of Rev. Grimshaw’s life written by local author Glynn Hughes and set a hundred years before the Greave murder. the Hell-fire Methodist preacher Grimshaw is considered to be one of the founders of the Methodist faith along with the Wesley brothers and was vicar of Haworth church before Rev. Patrick Bronte.

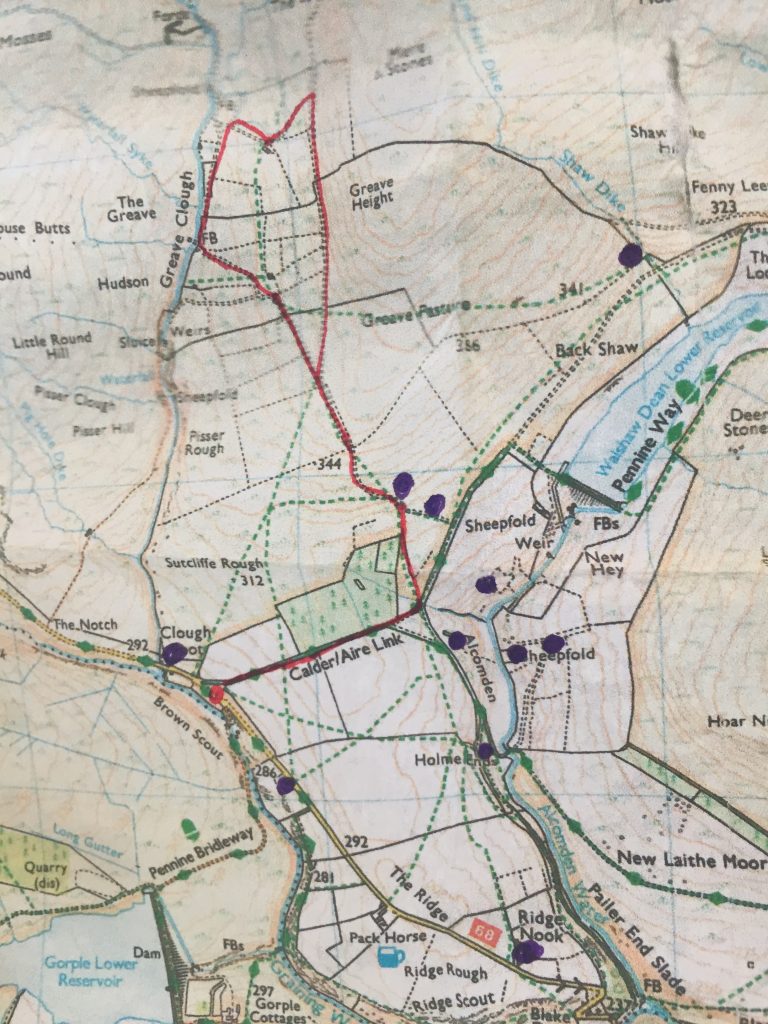

I met up with John Shackleton, a descendant of the victim in June, 2020, and I learned of his recent attempt to reach the site of Good Greave farm for himself. “I went up to Good Greave last year; there’s a track up from the Yorkshire Water road which goes up to Walshaw Reservoirs. Of the site of Near Good Greave farm where there were several buildings show little remains. If one persists and goes further you can see the ruins of the Far Good Greave farm but it’s exceedingly difficult to access.” He urged me not to try and access the site by myself but showed me a photo which show a door frame and lintel, all that remains of man’s presence in a peat ridden landscape with not a road or building in sight.

But luck came my way two years later when someone who had read my blog had walked to the ruined farm recently and offered to escort me to Greave farm. In the early years of the 20th century the three reservoirs of Walshaw Dean were constructed and the path we were to take was one of the maintenance roads for the reservoirs. Indeed the only people that we saw on our walk were from a construction lorry using the road. After passing a forest we headed upward, across Greave Pasture and, if it had not been for the presence of a solitary tree marking the spot the pile of stones that had once been Good Greave farm was barely distinguishable from the moorland amidst the long tussock grass.

It was obvious that many of the stones had been removed from the site but why? Who lived in such an isolated spot? Where did they buy food? How did they give birth? Early maps show a path to the farm that follows a more direct route to the farm but that path, though shown on the OS map no longer exists.

On his website John documents the story of the Shackletons of Widdop, putting them into their historical context. “The farming community of Greave comprised two, possibly three farmsteads has been in the possession of my Shackleton ancestors since 1790 that I can trace directly, but there were Shackletons living there four centuries ago. A 1604 survey of the Savile estate lists 26 farmsteads in Wadsworth, fourteen of which were owned by Shackletons and the document specifically mentions two at Good Greave.” 34 Indeed, in an article entitled ‘Travellers not made but born” the Todmorden and District News of February 1910 holds that “residents of Hebden Bridge show great determination and grit and a better exemplification of it could not be found than in the person of Sir Ernest Shackleton, who it was known had descended from old family which originated at Shackletonhill on the Wadsworth side.”

Perhaps that particular connection was wishful thinking on the behalf of the author. Shackleton hill The most comprehensive account of the ‘horrid murder’ of James Shackleton was in the Manchester Mercury, June 5, 1827. The article not only gives a detailed description of the character of the victim but conjures up the remoteness of the area around Greave farm and is worth recounting in its entirety. “Horrid murder, Wadsworth, near Colne in one of the wildest and most sequestered spots in Yorkshire, distance about 13 miles from Halifax and 7 from Colne, and within 2 or 3 miles of the Lancashire border in a district celebrated for majestic scenery. In this nook of the country, a place called Good Greave in the township of Wadsworth, is situated; the former is the scene of this horrid crime; it consists of only four houses, two them separated from the rest by a distance of about a quarter of a mile and the nearest them within a mile of the Halifax and Colne road. Stretching towards Colne, Haworth, or to Blackstone-edge in different directions, the township of Wadsworth consists of heaths and the deep ravines running between them. Nearly the foot of a steep aclivity, and within short distance of one of the gullies which carry off the waters from the mountains lived James Shackleton, an old man in the 7lst year of his age. In the dwelling where his existence was at last prematurely terminated, he first drew breath; that and the surrounding acres were his paternal estate, and by careful habits and moderate desires, he had rendered himself a man of considerable substance. Satisfied with much less of the good things of this life than he had the ability to purchase, in that he did enjoy a brother and sister, also advanced in years, but younger than himself, participated; the three having chose a life of celibacy, they were restricted so far as regards family and social intercourse, to themselves, except, indeed, their nephew, residing just at hand, who had a wife and three children.

On the night of Wednesday the 23rd about half past nine o’clock in the evening, the unfortunate victim, James Shackleton and a man named Richard Smith, an aged house-carpenter dwelling in the house until had completed a few jobs, were sitting over a cheerful fire of peat, waiting the return of Thomas Shackleton, the old man’s 34 brother, who had gone a short distance from home, on some business, relative to the formation of a new road. The sister Mary Shackleton had gone to bed, when six men entered the house, armed with bludgeons, and one of them, going up to James Shackleton, said “he wanted to purchase a cow.” This excited some astonishment in the old man, who replied that “that was a very odd time to come on such a business.” A demand instantly followed for his money, with which the old man hesitating to comply, the carpenter, Smith, said, “James, if you have any money, pray give it them.” Two cur-dogs in the house barked most furiously at the villains who struck them with their bludgeons. James requested them to desist doing so, and he would quiet the dog. They, however, still continuing bark, one of the men, with a knife or some other sharp instrument, made a desperate blow at the larger intending cut his throat, but he only made a deep incision in the neck the animal. The men insisting immediate compliance, James rose from his seat, and proceeded to a chest of drawers, from whence he took out two purses. These, the villains said, only contained copper, to which he answered that there was both gold and silver in them. They then told him that had £lO, in the house, which he had received for a cow that he had sold. This he denied, as, if the cow was sold, he had not yet received payment. The villains then struck the old man and the carpenter with bludgeons, but particularly the former, and demanded all he had, while some of the party took down two hams, and gun and pistol, which were hung up in the house. The carpenter, being alarmed for his own and his employer’s safety, got up and proceeded towards the door, to call the nephew, but was interrupted by two men at the doorway, armed with pistols, who declared that, if he stirred a step, they would blow his brains out. He then returned to the house, and the men were preparing to retreat, after the old man had surrendered his all. Fearing, from their ill treatment, that they would take his life, the old man had risen up, and gone towards the window, which had no open casement, and was calling for his nephew. From this circumstance, and the yelling of the wounded dog, it is probable a sudden fear seized the murderers. On their rather hastily retiring a voice was heard to exclaim “d–n him, shoot him,” and one of them, armed with a gun, seemed return to complete their crime, for on arriving at the end the passage, from whence he had a view of the man at the window, he levelled his piece, and shot him under the left shoulder blade, the shot penetrating through the body and coming out at the breast. He instantly fell, covered with gore, and having been laid abed on the floor of the house, the purple flood continued to flow until life was extinct. This closed the unfortunate man’s life, within half hour after the occurrence. Medical aid was sought soon as any one dared to stir out, but found, it was in vain. The nephew, John Shackleton, first became alarmed hearing one of the dogs make an unusual noise (probably when the wound was inflicted upon him) and laying down the pipe which he was smoking, he proceeded towards the house to inquire the cause. On approaching it, he saw a man standing in the passage, and supposing it to be his uncle Thomas who might have just returned home, shouted ‘ hallo’. To this no answer was returned. He then retraced his steps, and entered his own house; but not satisfied with what he had seen, he returned immediately, after locking the door 37 of his house, for his own family’s security. Having again sallied forth, the man in the passage ran at him, as he approached, and exclaimed “I’ll kill the devil,” inflicting, at the same time, a severe blow on one of his shoulders. It was then that the nephew became sensible of the danger. When precipitately retreating, he heard the cry of “d–n him, shoot him,” and instantly saw the flash of gun in the house. He ran to loose a bull dog which was tied up on his own premises, and while so engaged, the villains appear have left the house, for, on his again coming forth he heard nothing but a kind of murmuring noise, as if from the voices men, ascending the declivity, nearly at the foot of which the house was situated. The men were only about ten or fifteen minutes in the house, and on leaving it went in a direction towards Haworth, over the moors, but this, no doubt, was a feint to elude detection.”36 * Four days later in the Sheffield Examiner we read ‘The body of the unfortunate James Shackleton has been opened by a surgeon, who states that the wound was not inflicted by small shot, as was reported, since, in the course of his inquiry, he found two slugs, which had apparently been cut off from the handle of a spoon.”37 Someone was taken into custody but discharged and according to the obituary of James’s brother, Thomas, the murderers were never discovered. Sixty years later the murder was still a hot topic in the local press and it was still on the lips of people in the community. One local writer who was intrigued by the story was Tattersall Wilkinson, known as ‘Owd Tat.’ The youngest of twenty one children from Worsthorne near Burnley, the village where my mother-in-law grew up, he took an interest in astronomy, archaeology, geology and natural history. He spent some time with “old Sally Walton” who eked out a living in a two storey cottage close to the road at the bottom of Widdop pass. “Witch and boggart tales she thoroughly believed—and many a happy hour has your humble servant passed by the turf fire side listening to the tales of yore told by the venerable dame.” According to Sally the area around Crimsworth Dean and Pecket Well was “infested with a gang of desperadoes – poachers and house breakers. Sally tells us more about the carpenter who was staying at Greave– Richard Smith known as “Old Dick o’ Whittams” who lived at “Th’ ing Hey” near Roggerham Gate. I find these names so priceless and evocative of their time. Adding further fuel to the drama, the robbers who had ‘blackened faces,’ finding no ammunition for Shackleton’s gun “in a most deliberate manner took a leaden spoon from off the table and cut it into slugs.” 38 An inquest was held upon the body of of James Shackleton, at the Ridge public house, before Mr Stocks and a very respectable Jury.

Mr H. Thomas of Hebden Bridge, surgeon, stated that the deceased died of a gun-shot wound which injured the lungs, heart and pericardium. And after all the evidence had been heard the Jury returned a verdict of ‘Wilful Murder against divers persons to the Jury unknown’. A substantial reward was offered but the murder remains unsolved. The gun, however, according to Eric Shackleton, a descendent who contacted me from New Zealand, is in the possession of his brother. I needed to put to rest the gruesome story and so I sought out James’s burial record. Usually only the name, age and location of a person’s home is given here seven lines of minute text carefully squeezed into the column recording James’s burial at Heptonstall showing the devastating effect that this murder had on the community.: ‘Six men went to his house on purpose to rob – demanded his money-accordingly he delivered two purses to them – and they went out of his house after they had received them. He went to look out at the window. One of the robbers turned back into his house and shot him with slugs out of a gun so that he was both robbed and murdered in his own house about 9 o’clock at night, May 23, 1827.’ The inquest was held at The Ridge pub on Widdop Road. The inquest took place at The Ridge pub, now known as The Pack Horse. By law inquests had to be carried out in a public place and so inns were frequently used. I’ve been in the inn several times, most recently to say hi to the new landlord who recently moved there from The Cross Inn in Heptonstall. As I’d sat in the lounge six weeks ago I’d looked out at the open moorland and thought about the murder of my distant ancestor.

Later I was surprised to find an account of James’s death in a collection of poems written by another of my ancestors, Joseph Hague Moss. My Moss ancestors had split into two areas of expertise, the cloth industry and teaching. Joseph Hague Moss had been the founder of a dynasty of school teachers and when he died in 1861 his son gathered his poems together and had them published.

James of The Greave

Where the wild game in summer the heath flowers among,

Invite the bold sportsman to range o’er the moor;

And where deep rugged dells roll the echo along,

There has stood an old mansion a century or more;

Where far from the gay world, unskill’d to deceive,

Contented and happy dwelt “James of the Greave.”

In his lambs and his sheep, and the moorland close by,

He took great delight, and increased in wealth;-

A harmless old man, with a glance in his eye,

And a glow on his cheek, that gave picture of health;

And he might have sunk gently, like sunset at eve,

Had others been harmless as “James of the Greave.”

But the sportsman may chase the wild game on the moor,

And the innocent lambkins may bleat in the fold:

The man that beheld them with pleasure before,

Is wantonly murder’d at seventy years old:-

And long from the bosom remembrance shall heave

The wild note of sorrow for “James of the Greave.”

Greave farm lies off Widdop Road which drops down steeply in a series of switch backs to the bridge across a narrow bubbling stream called Graining Water. Once there was a chapel sandwiched between the stream and the road, Blakedean Chapel. The rear of the chapel was built into the hillside and access to its upper gallery was via one of the higher switchbacks on the road. I stopped to pay my respects to Isabella who is buried there.

Not another person was in sight, not a car passed me. Apart from the road there was no evidence of human activity. The landscape was pristine. But a hundred years ago one man made structure was to cause the death of another member of my family only ten minutes walk along the banks of Graining Water from this very spot.

Leave a Reply