Edgar’s sister ,Mary Harwood, married Mortimer Moss, a fustian manufacturer who lived at Nutclough House. How interconnected all these prominent families of Hebden Bridge were. Indeed. Only 2 months after Ada’s tragic death Edgar’s niece Bertha Moss, Mortimer’s daughter, married Claude Redman eldest son of Richard Redman The English Fustian Manufacturing Company had been founded in 1870 by Joseph Greenwood and alongside Redman Bros and Moss Bros ‘it earned a national and even international reputation as the most successful example of co-operative production in late Victorian Britain.’ Wow. That really is some accolade. It was a worker’s cooperative with each worker having an ownership stake in the business and the mill. Redman Bros manufactured the cloth and the Moss bros dyed it.

ABRAHAM MOSS

The patriarch of the Hebden Bridge Moss family was James, Mortimer’s grandfather, a former silk weaver, who had moved from Manchester across the Pennines in 1791. Over the course of his two marriages he fathered 15 children several of whom became prominent school teachers operating several educational establishments in the Upper Calder Valley, while the other children followed in their father’s footsteps of working with textiles, developing the fustian manufacturing business and building up an empire that would see their fabrics shipped all over the world. Fustian is a thick, hard-wearing cloth made from cotton and was once the staple fabric used for military and railway workers’ uniforms. There are many varieties of fustian ranging from corduroy to moleskin but it is all characterized by a soft velvety nap or raised pile. The basic cloth had extra looped wefts woven in as it was made. The rolls of cloth were then sent to specialist fustian cutters who were highly skilled craftsmen. In a well-lit room the cloth was pulled tight over benches up to 150 yards long and stretched with rollers at either end. The cutters would then insert a sharp knife with a long guide into the loops cutting the loops in a sweeping movement as they walked the length of the cloth, thus walking many miles each day. Hebden Bridge became synonymous with the manufacture of this hard wearing cloth and was often referred to as Fustianopolis. A fustian knife is the theme of a sculpture in the town square.

In 2021 one of the buildings closely associated with the fustian industry came up for sale and so I was able to take a step back in time as I climbed the steep narrow steps to the top floor of a three storey dwelling close to the railway station in Hebden Bridge. Bare stone walls lined the huge room which was well lit even on this rainy winter’s day. The end wall had fifteen long windows specially made to give as much light as possible to the fustian cutters.

I realised that I was standing in the very spot where Abraham’s great grandfather James Moss, a fustian cutter, developed his fustian business. From 1806 onwards his children’s baptism records give their residence as Machpelah and according to British Listed Buildings this was built in 1805. The 1805 date is taken from the Guardian Royal Exchange Fire Mark numbered 218779 which belongs to No. 12. This policy was registered 29th September, 1805 when the houses belonging to Rev. Richard Fawcett were described as “4 houses at present empty”, presumably of recent construction. Mortimer began his career as a fustian cutter before setting up as a fustian manufacturer himself, while his brother Abraham became involved in the family business first as a commercial clerk and then as a manufacturer.

Abraham’s father, Hague Moss, died when Abraham was only 11 years old and by that time the family had moved to Royd Terrace and so that is where I started my morning tracing Abraham’s life story.

Situated at the lower end of the Buttress, that unbelievably steep cobbled pack horse road up to Heptonstall some of the houses in Royd terrace are three storeys tall on the street, yet only the top storey rises above the hillside behind, the lower two storeys actually being built below ground level. This makes the buildings extremely damp and dark. One of the cottages was for sale so I was able to go and see for myself the small dark rooms imbued with an intense sense of claustrophobia. ‘Every man needs a good woman in his life’ so the saying goes. Abraham’s life saw his business flourish, so I think it’s fitting that that lady whom he shared his married life with deserves further comment. Abraham’s chosen partner was Mary Hannah Thomas, a tailoress, and daughter of Thomas Thomas, a coal merchant. I have his photo labelled Grandpa Thomas.

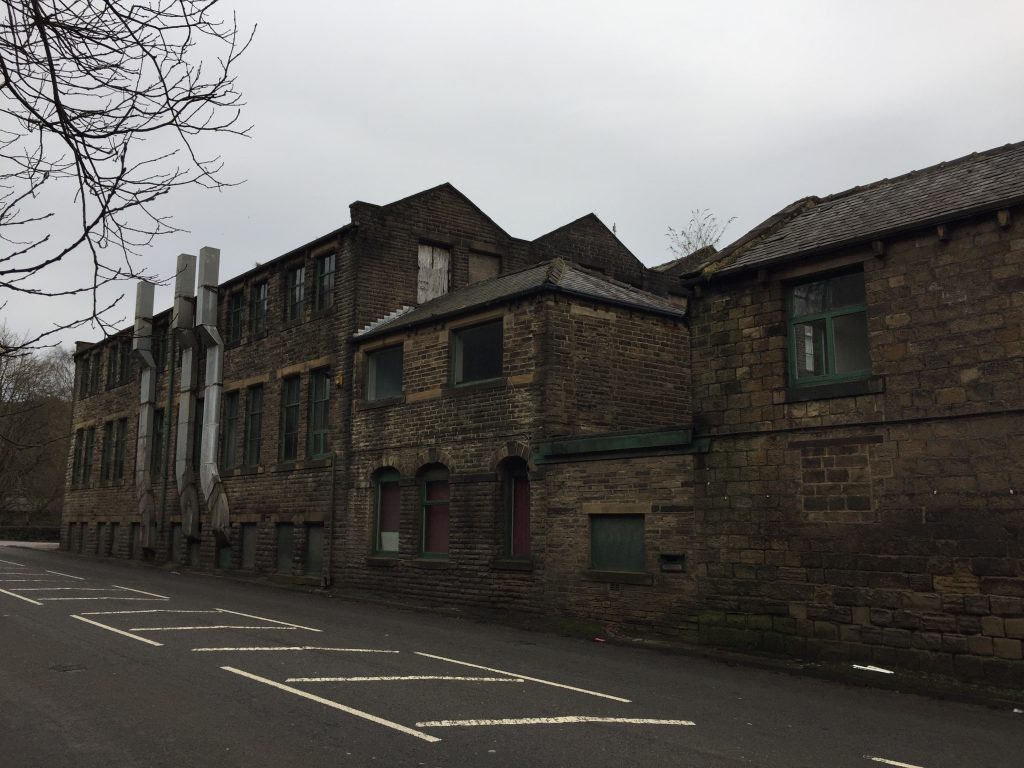

He sports an unusual beard known as a chin strap where a ruff of facial hair from the sideburns continues underneath the chin. There is no moustache. This gives him a very distinguished air, further enhances by his high buttoned morning coat. Hannah had been born at Royd Terrace in 1860, the same terrace that Abraham was living in in 1870. It’s quite possible that the two families were living in the terrace at the same time and that Hannah and Abraham could have known each other as children, playing together in the street since there was only a year age difference. When I’d first learned that Hannah’s grandfather and father had been coal merchants I’d thought what lowly beginnings she came from, referencing my own great grandfather, a coal merchant with a very humble lifestyle. So I felt somewhat surprised that Hannah had ultimately married one of the most prominent and wealthy men in the district, but then I’d forgotten my history lessons. Hannah’s father lived from 1831-1905, a period spanning the industrial revolution in the Calder Valley. The railway line from Manchester to Leeds had opened in 1841 with 5 trains per day stopping in Hebden Bridge. The railway was both a mode of transport that required coal to power it but it also enabled coal to be brought to the valley to provide steam power for the growing number of factories. The railway brought supplies for the manufacture of the textiles and provided a means of transport for the distribution of the finished products. So to be a coal merchant was to be on the forefront of the industrial revolution. When Abraham’s father, Hague died in 1870 his sons Abraham, James and Frederick Hague took over the business and from that point the firm was known as Moss Brothers. By 1881 Moss Brothers’ business had grown considerably and they had acquired a 3-storey building in Brunswick St for their warehouse. Just three months after their wedding in 1881 the first of seven children was born, a daughter, Beatrice Louise at 13 Melbourne Street situated just above Market Street. Today by the time I reached Melbourne Street the clouds which had looked threatening earlier in the day had decided to release their rain. There was a long row of identical houses on my left, their front doors opening directly onto the street and since there are no back doors the wheelie bins and recycling bags were strewn along the pavement. Flower pots and garden ornaments strove in vain to obscure next week’s contribution to the nearest landfill. I was in search of number 13, where Abraham and Mary Hannah set up home together. I made my way past a terrace of identical houses – 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11 that were over buildings. The underdwellings were accessed from Brunswick Street. But at number 11 the regularity stopped and I found myself confronted by a long lower building housing several apartments designated Melbourne House. I was so disappointed but I kept going. After Melbourne House the houses on my left began again, this time beginning with number 13, and yes, the door was open!

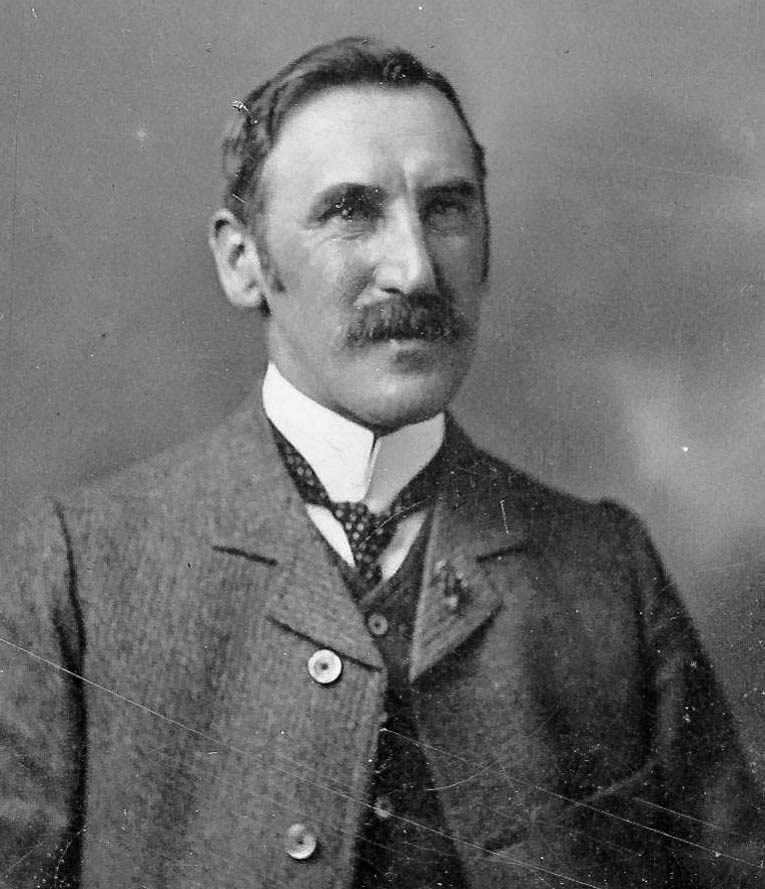

I tried calling ‘hello,’ a few times into the darkened hallway but though I could hear voices inside I didn’t get any reply. As I turned to leave I noticed a man tending a small plot of land on the other side of the street. I explained my quest and he told me that the long low building, now 49 Melbourne House, had once been a mill and had been converted into apartments around 2005. Ah, that was making sense. I’d found the upper entrance to Brunswick Mill with its main entrance on the Brunswick street, the street below. I thanked him and returned to number 13 where, after a few more hellos into the darkness a man came to the door. He was interested in my quest, especially when I showed him a photo of Abraham Moss. “Just a minute. I’ll go and get the house deeds.” A few minutes he returned with papers in hand showing that the building had been built in 1883 and had belonged to Mortimer Moss, Abraham’s eldest brother. I think the man was quite surprised by the yelp I let out realizing that I’d just found Abraham’s house, and Brunswick Mill, the family’s mill and the beginnings of Moss Brothers. For a few moments the man was distracted less by my yelp than by his mother-inlaw coming out to tell him to put on some shoes, since he was in stockinged feet and the rain was now quite relentless. Living next door to Abraham at number 15 was his brother, Frederick, also a founder of Moss Bros. It made perfect sense that the owners of the mill were living literally next door to it. By 1890 they employed over 200 people and traded with America, South America, New Zealand and Europe. They also had a London Office at 1 Trump St. 47 In 1901 they expanded and diversified, taking on dyeing and finishing, opening a dye works at Bridgeroyd at Eastwood between Hebden Bridge and Todmorden.

In the summer months Bridgeroyd would employ 70 people, whereas in the winter it employed 150. It was said that workers were willing work this seasonal pattern because Moss brothers were consider[ed] to be good payers.48 In 1902 Bridgeroyd became part of a group called the English Fustian Company Ltd. A workers’ cooperative which had been formed in 1870. By 2004 it was the last remaining mill in England making fustian and corduroy, employing just 8 people and in July 2004, Prince Andrew visited the company to present a Queen’s Award for enterprise in international trade to the company. I walked back into the centre of town and followed the course of Hebden Water as it flowed beneath the ancient packhorse bridge. Just beyond this ancient footbridge built in stone around 1510 I could see the familiar structure of St George’s Bridge, its elaborate cast ironwork painted cream and red supported by several carved stone piers with bratished stone caps. This Grade ll listed structure was built in 1892 with public subscription bridge.

One of the panels reads “St George’s bridge erected by public subscriptions with the aid of a grant from the West Riding county council committee – John Crowther, George Pickles, Abm Moss, Joseph Greenwood, J B Brown Sec.’ So Abraham was not only busy with the family fustian business he was highly involved with the running of the town and a member of the council. By the 1901 census Abraham is listed as a cotton fustian manufacturer, an employer and later that year a daughter, Phyllis Margaret was born, the last of seven children, born when both parents were in their forties. Their previous daughter, Vera, born seven years previously had died aged two. By this time the family had moved to ‘Brooklyn’ on an elevated street of large Victorian residences called Birchcliffe Road though known locally as ‘Snob Row.’

Brooklyn had nine rooms and the family had a live-in general servant. What a difference from Abraham’s early life on High Street in the densely packed housing. Soon after I moved to Hebden Bridge one afternoon I had climbed the steep hill of Birchcliffe Road. I don’t use that manner of motion flippantly. An indication of the steepness of the hillside is that its former name was Burstcliffe suggesting that there may have been a landslip there in former times. I had been in search of several buildings that had been lived in by, and in some cases specifically built for, my ancestors. So as I searched the street perched on the side of the hill with one of the best views in town, located above the smoke and smog of the valley I saw a sign on a gate: ‘Brooklyn. Please use the back door. These steps are dangerous.’ I’m not sure what caused me to take a photo of the sign on the gate but I was to find that these steps had played a very important role in the life, or rather, death of Abraham Moss.

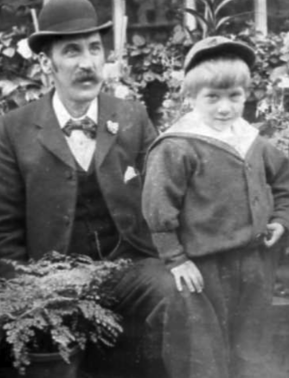

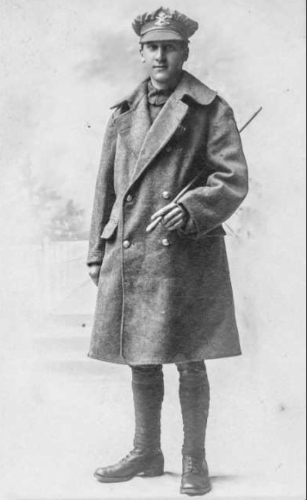

All the other imposing houses in the row had names like Hebden Hey, Riverdale, Oakleigh so perhaps it was the American name on this gate that had drawn my attention. The multicoloured stained glass panels in the front door glowed radiantly from an interior light. The bay window of the parlour extended to the upper storey and the view from the front extended over the Hebden Valley as Lily Hall peeked out at me from behind the trees. Through Ancestry.com I contacted some descendants of Abraham Moss and from his grandson I received this email: “I was given to understand that Abraham travelled to America sometime during the 1890s. It was after this visit that he named his house Brooklyn.” Not long after this exchange a copy of the photograph appeared in my inbox. There on the ship’s deck sits a moustachioed Abraham gazing out to sea from a cane deckchair.

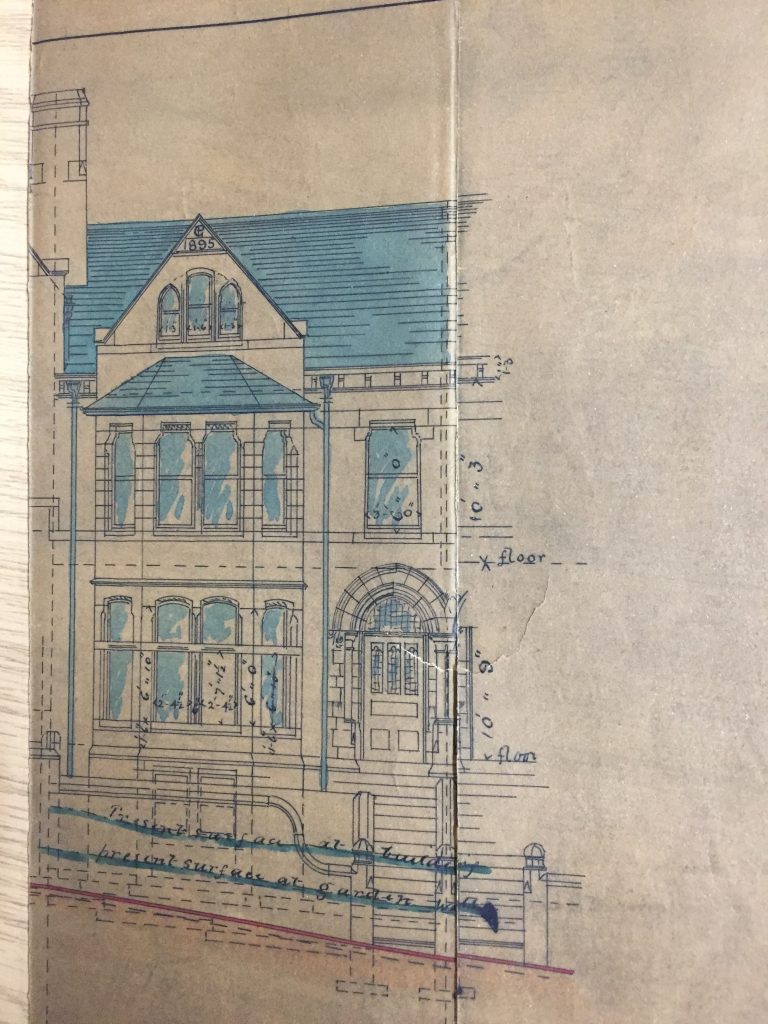

Like the other men around him he’s wearing a thick woollen or tweed suit with waistcoat, a pocket watch peeking out, and the peak of his tweed cap is shading his eyes from the sun. I had been able to view the architect’s plans for Brooklyn at West Yorkshire Archives though each leaf fell apart in my hands as I opened it.

It would appear that the plans were drawn up by John Sutcliffe, the same architect who had drawn up the plans for Ezra Butterworth’s house, Oakville, five years earlier. However, sadness and tragedy were just around the corner for the Moss family. Abraham’s daughter Phyllis died, aged 13. She had been taken ill at the boarding school she attended in Skipton, had been brought back home by motor car and had recovered well enough to have a ‘pleasant sojourn at Blackpool’ but succumbed to influenza shortly afterwards. Just three years later Abraham himself died, aged fifty seven. Imagine my horror when I read in a local newspaper that he had died as a result of falling down those very steps I had photographed. I do wonder, from a morbid sense of curiosity, if the people who put the notice on the steps know of Abraham’s accident. “Fatal fall at Hebden Bridge. Sad end of a well-known gentleman. We very much regret to have to announce the death of Mr. Abraham Moss, Brooklyn, Hebden Bridge, and especially so considering the melancholy circumstances under which happened. The gentleman on Wednesday evening was found laid in an unconscious condition at the foot of the steps leading to his own house, with a deep gash on the side of his head, and from this injury he died at two o’clock yesterday morning without regaining consciousness. So far as we can gather from particulars collected from various sources the circumstances are these: Mr. Moss had been down in the town and parted from Mr. A. Moore at Top o’ th’ Hill about ten o’clock on his way home. In the course of half an hour or so, Mr. T. Fenton Greenwood was on his way home to Eiffel Street, and when he got opposite to the gate the residence Mr. Moss he heard some deep breathing, but as he had no means of making a light and the night being very dark, he could not make out any object. Mr. Ernest Whiteoak, Eiffel St., came up almost immediately afterwards, and struck match and the light revealed Mr. Moss laid at the bottom of a flight of dozen steps, with his head resting in a large pool blood and perfectly unconscious. On the right side of his head there was a large wound from which the blood was issuing. Mrs. Moss was acquainted with the fact and her husband was carried to the house and Dr. Sykes summoned, and that gentleman found that Mr. Moss was suffering from fractured skull. Whether he had fallen from the top of the steps or not does not appear clear, but the sloping asphalt from the top of the steps was very slippery. Judging from the position the body it would appear that Mr. Moss had fallen backward and his head had either struck the wall or the steps in his fall. The facts have been reported to the Coroner. The news of the sad occurrence created quite sensation in the town yesterday morning. Mr. Moss was well known in Hebden Bridge and district. He was the younger son the late Mr Haigh Moss, and many years was associated with his brothers in the fustian manufacturing, dyeing and finishing business at Brunswick Street, Lee Mill and Bridge Boyd, up to few years ago, when he retired, and since then he has not followed any occupation. He was one the directors of the English Fustian Association up to the time his death. He took great interest the affairs of that body, and for a term was its chairman. For many years he was a very active member of the Hebden Bridge Commercial Association. He was an enthusiastic member the local Angling Club. He took interest in electricity, and according to his own story, he along with the late Mr. S. Blackburn installed the first telephone in Hebden Bridge, connecting the house of one of his brothers to the firm’s premises. Mr. Moss, who was 67 years of age, leaves widow and five children. Two his sons are serving in the army, Walter Edward in France and Reginald in India.” I thought of Mary Hannah. Both sons were miles away from home serving in the first world war and her husband had died suddenly and tragically on his own doorstep.

She continued to live at Brooklyn for the rest of her life, outliving Abraham by 30 years and their daughters Beatrice Louise and Edith Martha both remained unmarried, living with their mother at Brooklyn until their deaths in 1955 and 1961 respectively. Marian married Joseph Redman, a raincoat manufacturer, who had also grown up on Snob Row. In later life they moved to Ilkley where, in honour of their earlier life they named their house “Hebden.” Reginald, returning from India became a cotton manufacturer and was an accomplished pianist.

He lived with his wife Francis in Mytholmroyd. When Abraham died he left just short of £ 40,000 to his wife. Today that money would have be worth about £ 3 million.

My great grandmother was Elizabeth Cockcroft (nee Moss) and my GG grandfather James Moss. I have original birth / marriage certificates and original letters to my great grandmother Elizabeth addressed to Machpelah.