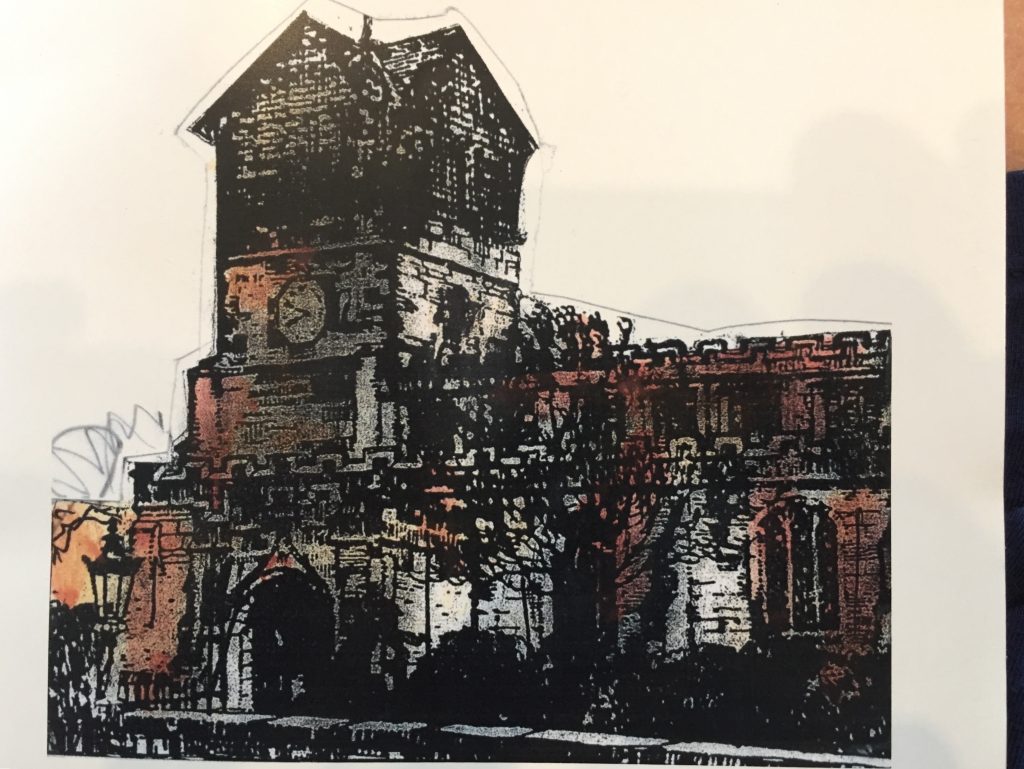

I’d first visited Middleton with Rachel in the summer of 2015, having discovered that some of my ancestors had associations with that town, and several were baptised, married and buried there. We only visited the church and it was closed sir we wandered around the overgrown graveyard. The church is situated on a hill overlooking some of the industrial sprawl of Oldham. We were both intrigued by the rather strange wooden tower which tops the stone tower. Here’s the writing from my journal about our visit: Wed July 22. ‘It was 3 pm by the time we set out to do a little more ancestry hunting – this time to Middleton and Heywood, which require going around a lot of roundabouts several times! St Leonard’s in Middleton is perched alone today on a spot which used to be the centre of this silk weaving town. The adjacent cemetery was very overgrown. In the porch was a plaque saying that one of the Hopwood family donated a silver chalice. I think we have a Hopwood from this church in our ancestry.’

Middleton would have looked very different today had it not been for the famous architect Edgar Wood, an influential proponent of the Arts and Crafts movement. He sent his life reshaping the town and designed more than 60 buildings in Middleton and its vicinity. St Leonard’s Parish Church, Queen Elizabeth Free Grammar School, The Olde Boar’s Head and the Edgar Wood Centre, Long Street Methodist Church all form part of the Golden Cluster.

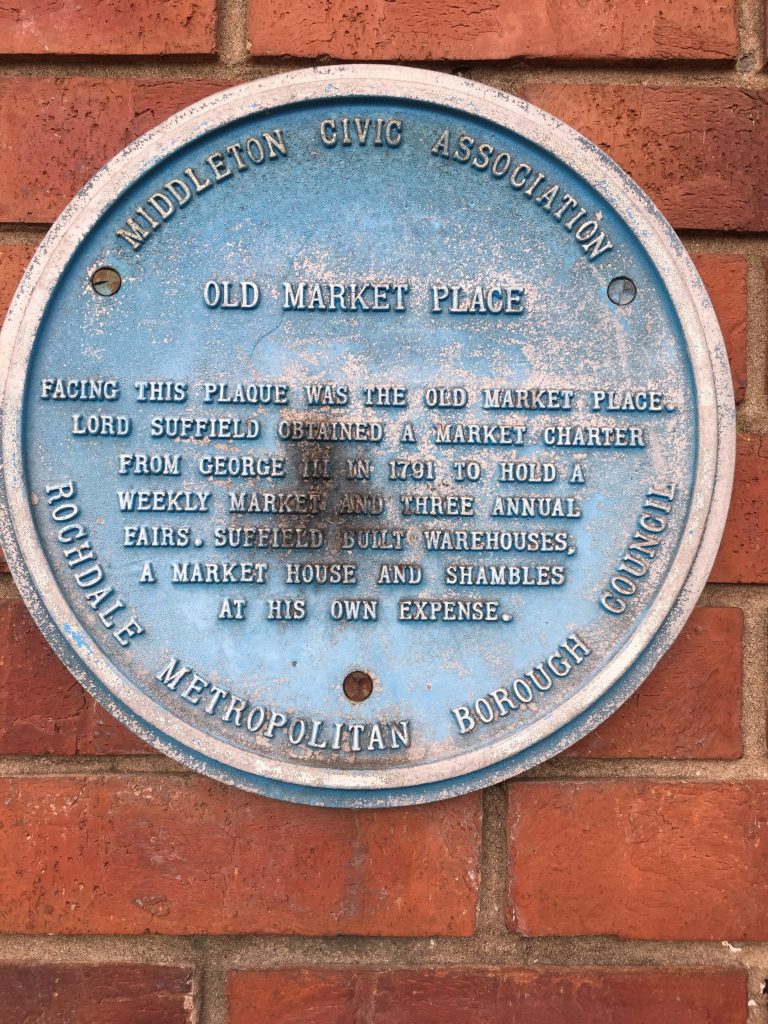

Middleton gained its market charter in 1791. In the late 18th century Middleton was a village with 20 houses, and yet it boasted a grammar school. Like many other villages and towns in the area, the 1780s began to see a growth in population and trade. Middleton was a centre for silk manufacturing at that time, and silk weaving was still described as the chief trade in 1901, alongside a fast growing cotton trade, with its calico printing, bleaching and dying. Middleton handloom weavers were depicted by the artist Frederick W Jackson. Frederick W Jackson (1859–1918) was born at Middleton Junction, Oldham in 1859.

Boar’s Head pub

Then last autumn I’d visited with Ed and again the church was closed but we’d taken a walk through the town centre, gone into the library and seen some of the buildings designed by Edgar Allen. It was in the library that I’d seen a flier for Lost in Manchester Found in Vegas.

Modern textile banner

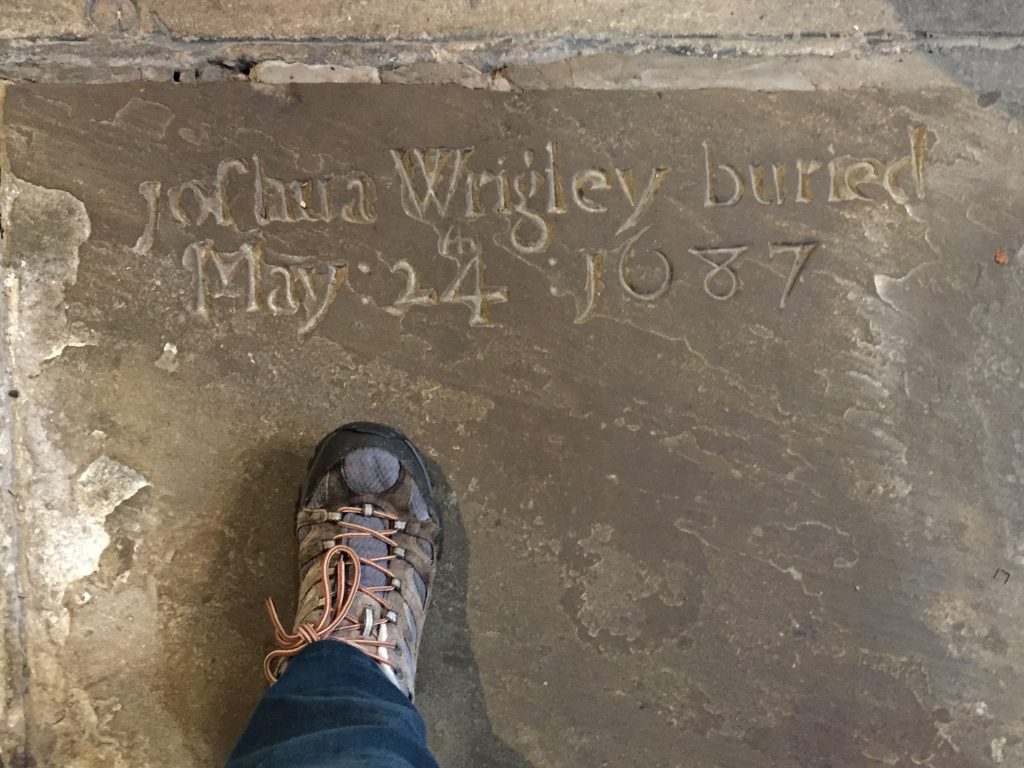

Am I related to this Wrigley? He died on my birthday!

The original font where my ancestors were baptised has been recarved

The box contained loaves for the poor

I’d exchanged a few emails with Moira from the church office who, when I had mentioned that I had Hopwoods of Middleton in my ancestry had responded – Are you related to Hopwood Dupree? I’d never heard of him so looked him, up and he’s a descendent of the Hopwoods of Hopwood Hall. He’s currently trying to restore the place.

Bows belonged to the Middleton archers

Assheton funeral helmet back in a secure place

I was taking up the opportunity to go to Middleton – train to Rochdale, train to Mills Hill, bus to Middleton because the weather forecast was predicting a rain-free day and it wasn’t until I got up and saw a sunny sky that I decided on the spur of the moment to go. But by the time the train and passed through the pennine tunnel it was sprinkling with rain and as I arrived in Middleton it was pouring down. It was market day and I sheltered for a moment under some awning but then decided to continue up the hill to the church. I’d look around the market on the way back.

Boar’s head coat of arms on the rood screen

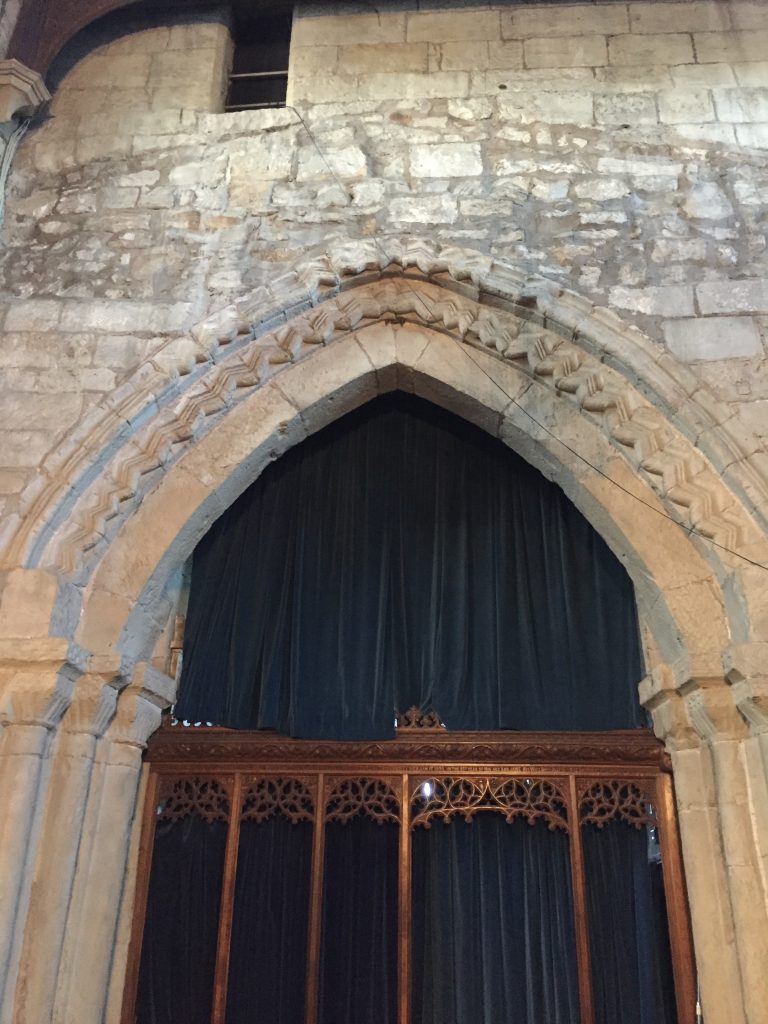

reusing the Norman dogtooth molding

Harmonium

Tudor linen fold panelling

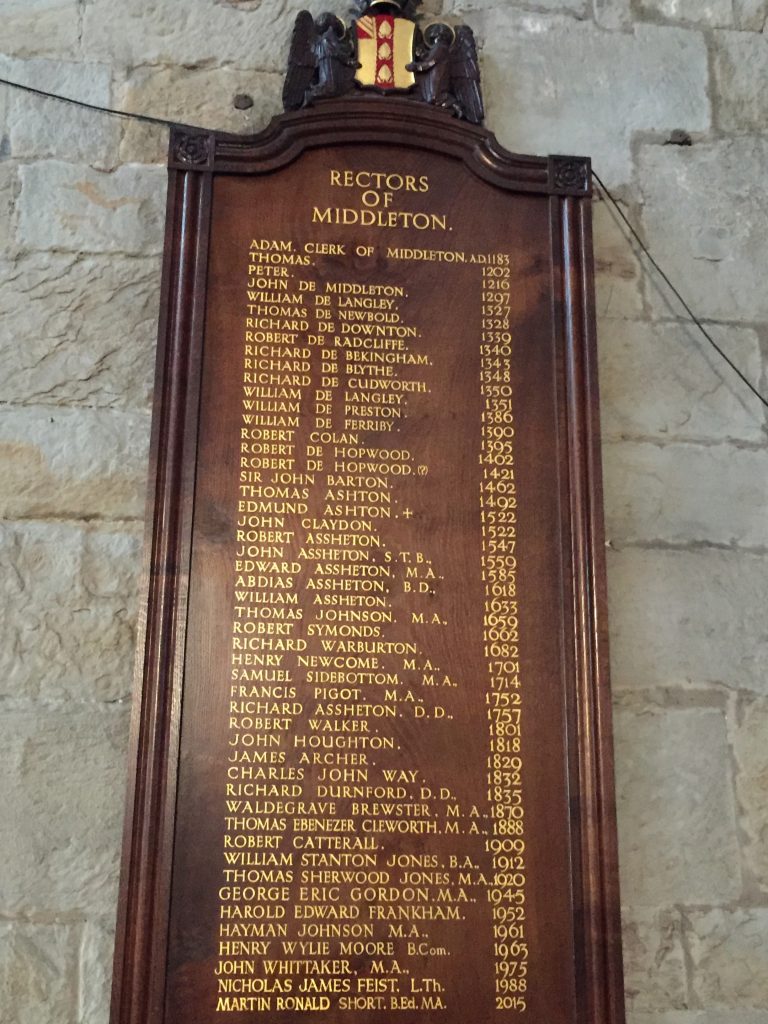

Moira had told me to ring the bell of the church office and I was glad to know that there was someone inside, to not only let me in, but be on the premises while I looked around. Moira handed me a guide book, asked me to sign the guest register (which aids in funding) and then left me to it. I spent a leisurely hour and a half taking in as much as I could but I really feel I barely scratched the surface. It’s a Grade 1 listed building. I could hear the rain pounding on the roof above the exposed wood, a sound I’m not familiar with in churches. Apparently it’s because the roof is stainless steel rather than lead. Vandals were forever stealing the lead so it’s been replaced and makes a hell of a racket when it rains heavily. The guide book is entitle “ The church with over a thousand years of history.” In 1890 the Rev C B Ward said, “The people of Middleton are distinguished above all the people I have ever met, for the peculiarly fervent love that they have for their parish church.” Around 870 a Saxon church stood on this site, replaced by a Norman church around 1100. This was replaced by the Langley church in 1412. Thomas Langley 1363-1437 became prince Bishop of Durham and served terms as chancellor to King Henry iv, v, and vi. It’s documented at Durham Cathedral that the body of St Cuthbert stayed in Middleton, and with him the Lindisfarne and Stonyhurst gospels. In Cuthbert’s day Lancashire was still largely Welsh speaking (Cumbric) with a British/Celtic identity. The Norman church measured 40’ x 20’. It’s dogtooth molding above the arch was later reused in the pointed tower arch and in the arch over the pulpit. What is now the tower arch was once the principal door of the Norman church. The weathered columns are evidence that it once faced the elements outside.

Middleton archers depicted and named

Thomas Langley was born in Middleton and he built a new church at his own expense in 1412 , and around 1510 Sir Richard Assheton, lord of the manor and hero of the Battle of Flodden, 1513, extended and rebuilt parts of the church, raising the height of the roof and adding the clerestory. The wooden belfry was added in 1666.

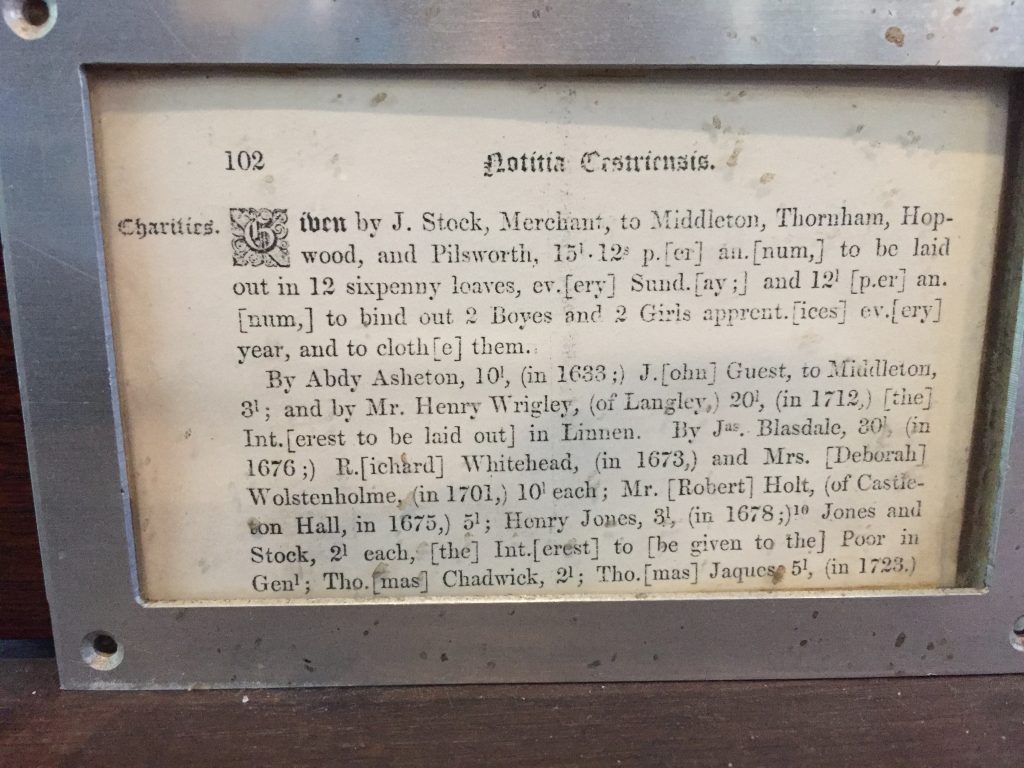

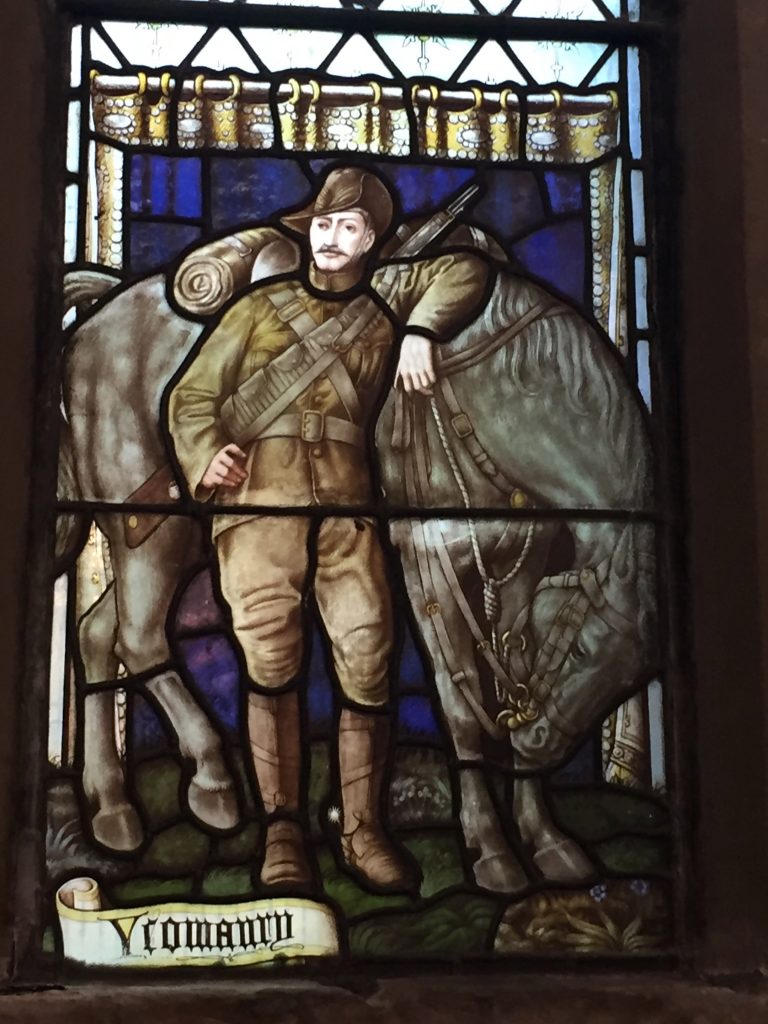

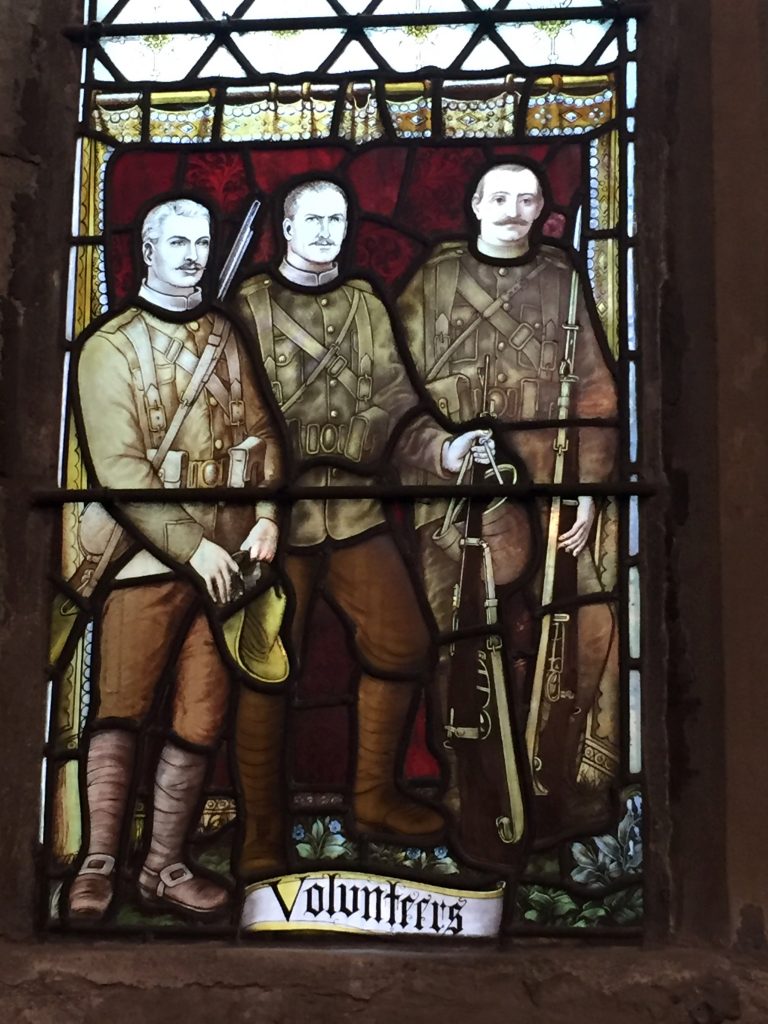

Remarkable stained glass

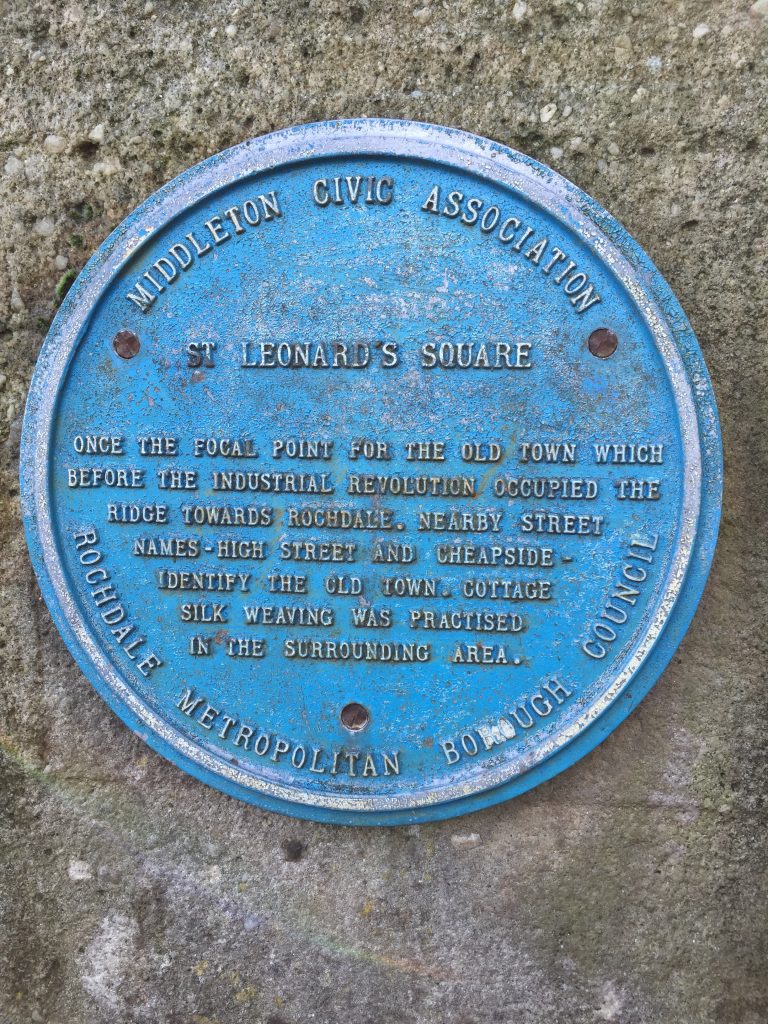

The parish of Middleton included Great Lever, Ainsworth, ash worth, Birtle-cum-Bamford, Pilsworth, Hopwood, Thonham and Middleton. Markets and fairs were held in the square. A blue plaque now marks the site. The current pews dated from 1867 and many gravestones were removed to the churchyard. The south porch shows evidence of sword and arrow sharpening on the external moulding. The main south door is attributed to Langley and the large wooden door with its wicket and drawbar is possibly from Langley’s time. The medieval font was recurved in 1847 by church architect George Shaw and around its rim are lead infills indicating where the locks and hinges once were. The portable harmonium, probably used at choir practice was purchased in 1889 for 6 pounds. Prior to the reformation mass was celebrated for the Hopwoods in their chapel. The pew was enclosed during the Jacobean period c. 1620. It was wonderful Tudor linen fold panelling and elongated barley twist spindles. Hopwood burials took place beneath their pew. The famous Assheton memorial brasses ‘the finest in Lancashire’ are by the altar. On top of the parclose (screen) is the Assheton funerary helmet adorned with the boar’s head, the family’s crest. The helmet was stolen from the church in the 1960’s but was recognized by a London antique dealer and it was returned. In 1911 the chancel was refurbished by parishioners. The 19th century choir stalls were replaced and the floor tiled. The flooded window is 500 years old and shows Sir Richard and Lady Anne Assheton and their squire together with the named – amazing – contingent of Middleton archers and chaplain who would have accompanied Sir Richard to Flodden field – Sept 9, 1513. They look like individualized portraits. The oldest brasses , by the altar, are those of Sir Richard Assheton and Isabel Talbot, 1507. Finest in the north of England according to the Brass Memorial Society. Facsimiles of the brasses are available for brass rubbing. The medieval rood screen avoided destruction during the reformation because the carvings were entirely secular. Cardinal Langley provided endowments for two priests to ‘teach one grammar school free for the poor children of the parish.’ The school continued here until 1586 when a new school was built – the Grammar school. Memorial window to Middleton men who fought in the Boer war, designed by George F Bodley, 1827-1907. The illustrated faces are those of some of the soldiers who went to South Africa. The present shallow pitch name roof of 1907 designed by Edgar Wood. The ‘leger’ stones in front of the screen included Wrigley (Langley Hall). There are 9 bells from 1614-1891. The Nowster was rung every evening from 9.50-10.00 to warn people to get off home. This tradition began as a curfew bell at the time of the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 and continued until the outbreak of WW ll.

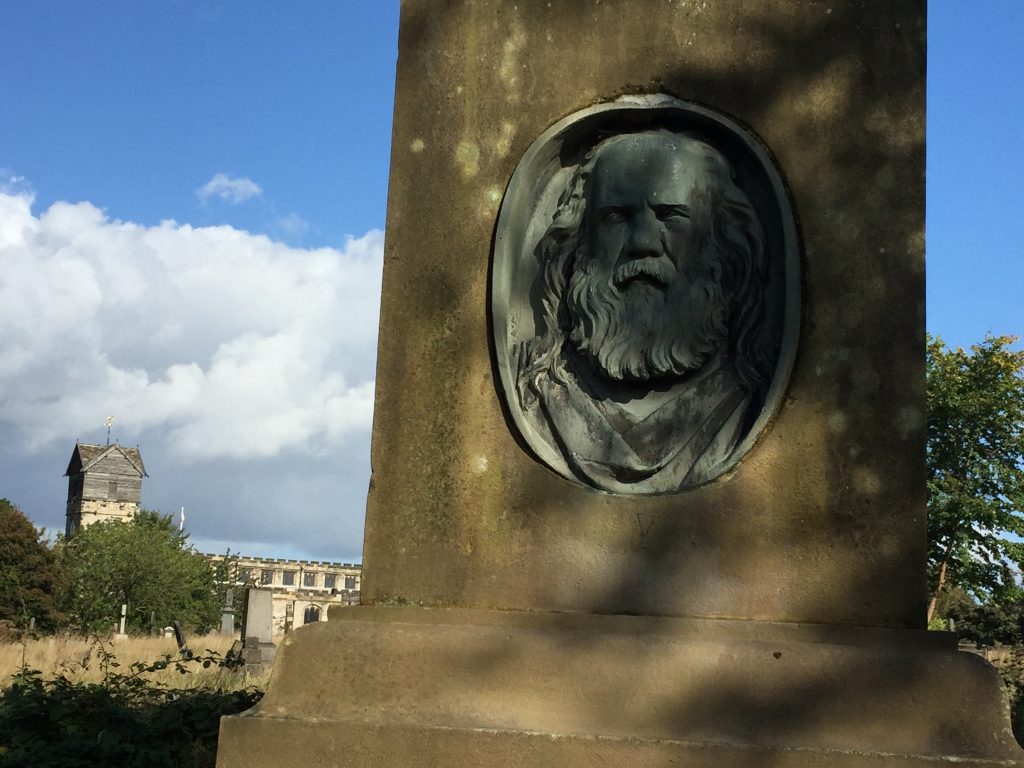

From the church I took a walk in the cemetery where a man with green and pink hair approached me. At first I was a little apprehensive. There was no-one else in site and he made a bee line for me crossing several flat stone graves to reach me. He was out walking his dog. He presumed I was in search of Samuel Bamford’s grave and he was eager to guide me to it. I’d been to see a movie about Sam Bamford at Manchester Museum, and i’d seen the Peterloo movie, made to coincide with the 200th anniversary of that massacre. I’d discovered that my ancestors were living in Middleton at the time of the Middleton Luddite riots in 1812 and so I presume that my ancestors who were weavers just like Sam Bamford could well have participated, or at least, were eye witnesses of the burning of Burton’s mill in Middleton. As it happened I’d just come to the end of reading Glyn Hughes’s ‘The Rape of the Rose’ and the final section describes the burning of that mill. It was reading that chapter that had led me to Middleton this particular day.

The huge cemetery

Memorial to Sam Bamford

After exploring the cemetery I crossed the road and had lunch at the old Boar’s Head pub, where, quite by chance, i ended up sitting in the Sam Bamford room, decorated with photos of Sam and his family and other associated items.

The sessions room in the Boar’s Head

Lunch in the Sam Bamford room

Lovely view of St Leonard’s and its wonderful wooden belfry

18th October 2021 at 11:42 am

As someone who only left Middleton a couple of years ago after 60 years I very much appreciate this piece.

It is put together in a way that makes easy reading rather than some of the drier writings.

Well done

12th November 2021 at 9:24 am

Thank you so much. I appreciate your comment.