“Seldom has the district of Hebden Bridge been so greatly moved as it was last Saturday evening by the news of a terrible tragedy which happened at Blakedean whereby a well known local lady lost her life.”

On May 28, 1909. Mrs. Ada Harwood, with her husband Edgar, her 16 year old nephew George A. Smith, and Miss Milnes, her partner in the dressmaking and millinery business they conducted in Hebden Bridge had driven up to High Greenwood, above Heptonstall earlier in the day to stay with Mrs. Priscilla Clayton for a few days. A 66 year old widow from Shropshire Priscilla ran the 9 roomed boarding house. After a few days stay in Heptonstall the family were looking forward to taking a ‘pleasure trip’ to Norway, land of the midnight sun, with some friends. From the newspaper account I read: “After tea they went for a walk in the direction of the trestle bridge, only a few minutes walk from the house. Mrs. Harwood and her nephew were a little apart from the others, and, as hundreds have done before, they stepped into one of the recesses to better enjoy the view. The youth doubted the safety of the place. It struck him as being rather flimsy. “Do you think it safe, auntie?” he asked. She replied that it was, having no knowledge of the awful danger which lurked under her feet: and sprang on tiptoe, or, as one might say, “prised” on tiptoe, to make a little test of the platform’s strength. And at that instant the tragedy was upon them they could not avert it, though only a foot’s space from safety.

The wood cracked and gave way beneath their feet. Part of it went hurling down to the bed of the stream far below, and Mrs. Harwood fell with it. Overcome by the shock, her nephew found himself clinging to the railing, with no foothold. His walking stick fell through the gap into the gulf. How he got back to the comparative safety of the permanent way he does not remember. One can understand what a fearful shock it was to him as, clinging there and looking down as he saw his relative falling into that great depth to certain death. Mrs. Harwood was beyond help. Her lifeless body lay on a grassy plot just clear of the stream. Her injuries were fearful. They were, in fact, indescribable. Her head and body had apparently struck the framework of the bridge directly after disappearing through the hole, and probably instant death or merciful insensibility was caused before the ground was reached. In a second or two this peaceful valley had been transformed, for the watchers, into a scene of painful tragedy. Pending the arrival of the ambulance the remains of the unfortunate victim of the disaster were reverently conveyed to a spot near the stepping-stones at Blakedean, being carried thence under difficulties by P.C. Matters, and others. Bad news travels fast, and this news was all over the district soon after eight o’clock. From that time the main streets of the town were occupied with hundreds of people discussing the sad event.” Over one hundred years later I found myself standing at the very spot where the tragedy occurred.

Beside me was one of the enormous stone stanchions that once formed the base of a trestle bridge 103 ft above the river built to carry the Blake Dean railway line. The railway had been built to take men, equipment and raw materials from the shanty town near Heptonstall to the site of three dams that were under construction at Walshaw Dean to provide water for the rapidly expanding town of Halifax.

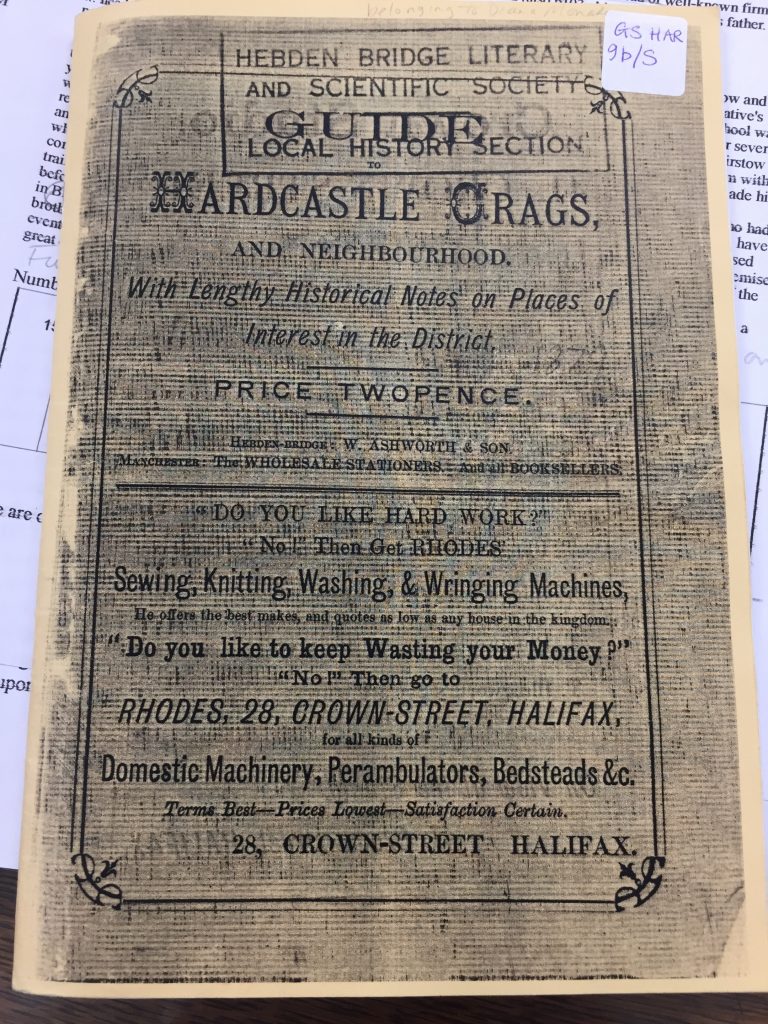

The architect was a local lad, the son of a quarry owner, born in Haworth in 1843. His name was Enoch Tempest and he lived up to his name in more ways than one. A tornado of a man he was a notorious drunkard who once woke up in New York after a drinking binge with no recollection of how he got there. He returned to England, mended his ways and made his name as the famous teetotaler builder of reservoirs. The railway serving the construction site had opened just eight years before Ada’s accident and the trestle bridge had become one of the ‘must see’ sites of the Hebden Valley, along with the rocky outcrops of Hardcastle Crags, sometimes known locally as Little Switzerland though that nomenclature requires more imagination than I can muster.

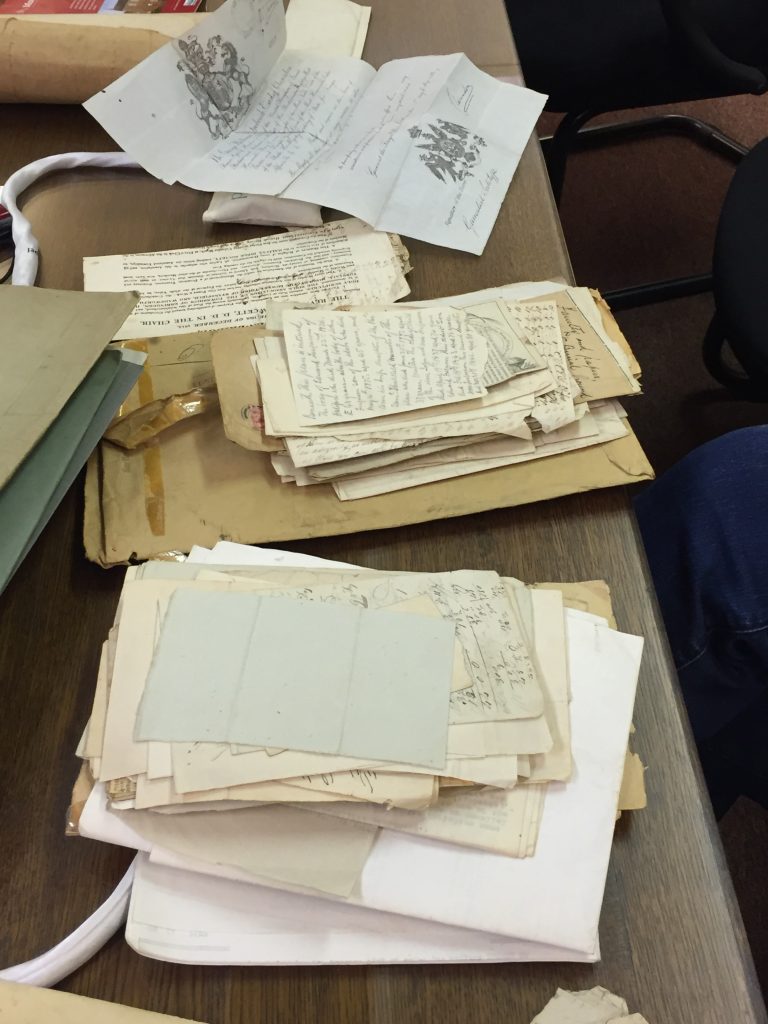

In the Hebden Bridge history society’s archives I’d found a fragile copy of ‘A Guide to Hardcastle Crags and neighbourhood’ compiled by an unacknowledged author in 1879. From it I learned that it had become a common practice for tourists to walk on the bridge for the sensation of looking down from so great a height. At the inquest into Ada Harwood’s death the contractors’ foreman said that notices had been put up at both ends of the bridge saying ‘Notice: no person allowed on these works or tramway except workmen on business. Others will be prosecuted.’ But visitors constantly pulled the warning notices down. No criminal negligence was found but the jurors recommended that the signs should be replaced and if possible to erect barricades at the weekends when there were no works’ trains. My attention was drawn to the fact that the chairman of the jury at the inquest was none other than Abraham Moss, one of my family members, who was to come to his own extraordinary and untimely death just eight years later. From my spot beside the babbling stream I crossed over Hebden Water and followed a steep rough track through open fields leading me directly to High Greenwood, the boarding house where the Harwoods had been enjoying their mini break. It is a beautiful stone building dating from the late 1700s set just off the lonely Widdop Road speaking of wealth and privilege of its original owners with its symmetrical façade centred on a front door made all the more impressive by the triangular pediment above.

Today it’s surrounded by a well- maintained lawn and has expansive views in all directions. Close to the front door is a weeping willow tree causing me to wonder if the person who planted it knew of the association of the house and its unfortunate overnight guest. In this remote place there’s a feeling of vast expanse heightened this May morning by the calls of the curlews who ‘Hang their harps over the misty valleys, ’ their bleak, windswept calls as they sweep and glide above me mirror my sentiments today. It doesn’t surprise me that in 1920 this very spot was the filming location of a silent movie, Helen of Four Gates, written by Heptonstall resident Ethel Carnie Holdsworth, an important working class social activist and feminist. The raw scenery and the hard life of the local farmers is beautifully portrayed by pioneer film maker Cecil Hepworth, and it was to this very spot that Ethel brought Cecil to show him this remote location with its scattered farms and persuaded him to shoot the movie here.

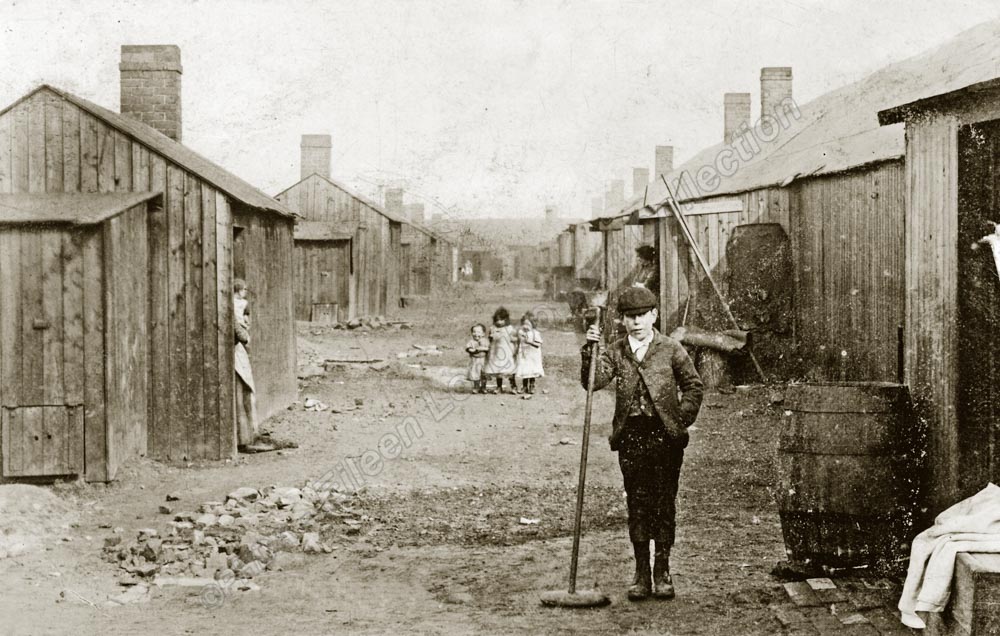

Its grainy black and white images heighten the hardships of the isolated life for these hilltop residents as the heroine battles against the abuse she receives not only at the hands of her family but those inflicted by the elements. I soon came to Draper Lane with its stretch of flat farm land perched high above the tumultuous rocks and crannies of Hardcastle Crags. Once the site of Dawson City, named after the famous Canadian shanty town synonymous with Klondike gold rush, these fields had been home of the builders who had constructed the narrow gauge railway which ran for three miles to the reservoir site – and its trestle bridge.

By 1901 there were 22 huts accommodating about 230 men with large dormitories and wash houses provided for single men. As wives and children joined their husbands the impact was felt by the local community of Heptonstall and a spare room in the school master’s house was brought into service for the additional thirty children living in the shanty town. Sanitation in the new city presented a major problem and when outbreaks of typhoid and smallpox broke out a tent was set up to serve as a field hospital capable of caring for fourteen patients but it blew down in a gale! I can definitely testify to the strength of the wind as it lashes the few trees that manage to survive in this barren landscape and I’ve become in danger of being blown over several times as I’ve walked along this hilltop.

As I continued my walk back down into Hebden Bridge the entire town opened up before me, the terraced houses clutching to the steep hillsides at crazy angles, as impressive in its own way as any hilltop town in Italy. Reaching my home I passed along Market Street, one of the small town’s main shopping streets. Passage along the narrow pavement is usually an obstacle course with tourists stopping to gaze into the nicely decorated windows displaying their wares while tugging at dog leashes in a mostly successful attempt to prevent them coming into contact with the buses, tractors and heavy goods vehicles for whom this is the only road along the valley floor.

One of these shops had been the location of the millinery business that Ada had operated with her business partner, Mary Ann Edith Milnes.

When Ada was buried in the old burial ground at Birchcliffe chapel even though it was mid May “throughout the funeral obsequies rain poured down. Blinds were drawn in cottage and villa alike showing sympathy and respect.” Following a short service at Hurst Dene Ada’s body was carried across the road by seven deacons.

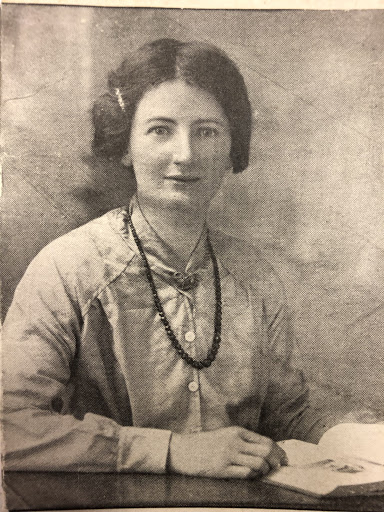

In the service the minister, Rev A. J. Harding stated, “ Her loyalty to the church of Jesus was the most conspicuous feature in a character notable for many admirable traits.” Just over a year after Ada’s death a stained glass window and memorial brass were erected in Birchcliffe chapel, the first window of its character to be installed in the church. The glass was a representation of William Holman Hunt’s ‘Light of the World’ and it was placed by the Harwood pew. “The window a remarkably beautiful reproduction of the marvellous picture : the colouring is exquisitely done, and a credit to both the designers and the executants, Messrs. J. Harding, Birmingham. A massive brass tablet has been put behind the pew recently occupied by Mrs. Townsend, bearing suitable inscription, and is a very appropriate accompaniment to the window. The newspaper account of the unveiling mentions the Worsick and Townsend families’ long devoted and honourable association with the church. Ada’s grandfather, Henry Worsick had attended Sunday school there and during the ceremony it was said of Ada that “She had given of her life’s best energies to the cause at Birchcliffe. She had always been ready to do that work, and willingly too.” “For Mrs Harwood it was a sudden entrance into glory, at quarter to seven that Saturday evening.” I was excited to discover that the stained glass window is still there in the Birchcliffe chapel and in January 2022 I made an appointment to view it. Until my own research the heritage centre did not know to whom the window was dedicated. I was taken on a wonderful behind the scenes tour of the former chapel, much of it now the Pennine heritage centre with its photographs, art and dance studios, and part of it is maintained as a wedding venue.

Although the structure of the building is in good condition the interior furnishings are either gone or in a state of bad repair. A mosaic floor covers the hallway at the entrance to the building and there is some wonderful tile work on the walls. Part of the pulpit is upended and stored against a wall and much of the plasterwork is missing, revealing the wooden framing of the building. The chairman of the Trustees and the new Heritage Manager even pulled up the flooring covering the sunken baptismal font which was used for the total immersion of the people being baptized. What had been the body of the church is now subdivided into various studios and I was shown into the studio containing the window. The studio belongs to a needle fabric artist and it was an honour to see her marvelous work on the shelves and tables in the room, overlooked by Ada’s window.

As I continued my research into Ada Harwood another incident in this story stopped me in my tracks. Less than three months after his wife’s death Edgar married Mary Ann Edith Milnes, none other than Ada’s business partner in their dressmaking and millinery business, and a woman who had shared a home with Ada and Edgar throughout their married life. I needed to know more about Ada – and Edgar but I’d save that for a winter’s day.

Six months later after visiting the site of the trestle bridge I’d woken to the first snow of the season, nicely timed between Christmas and New Year. The sky was a shade of blue that I hadn’t seen in weeks, with puffy white clouds gently gliding across the sea of blue. The landscape took on the aspect of a monochrome photograph with black trees silhouetted against the white fields of snow and the dark stone walls wore hats and eyebrows of white. But I was eager for Edgar’s story. I’ll just take a quick look and see if there’s anything of interest in local newspapers of his time before I head out for a chilly walk. Six hours later, the sun had disappeared over hill above Weasel Hall and I was still absolutely absorbed in the lives and ancestry of Ada and Edgar. Ada was the third of four daughters born in 1859 at Heppens End to George Townsend , a shuttlemaker and his wife Sally, nee Worsick. Heppens End is a terrace of four cottages close to the river in Hawksclough between Hebden Bridge and Mytholmroyd. Today the cottages are the only buildings that remain in what is now a large industrial estate, just across the River Calder from the now leveled Walkley Clog Factory which burned down in August 2019.

I pass the cottages at least once a week on my walks along the canal and now I knew of my connection to the cottages I stopped for a moment to take a closer look at the row of three cottages. Within minutes I found myself chatting to one of the current residents who was only too happy to bring out a framed photograph of the terrace taken in the mid 20th century. It was absolutely dwarfed by huge factory buildings on three sides. When Ada was born there was a saw mill backing onto the river. By the time Ada was 12 in 1871 the family had moved into the centre of Hebden Bridge to Carlton Street where her father George was a furniture broker and fustian finisher. That’s an interesting combination. Like Ada her two older sisters were also tailoresses. By the age of 22 Ada was described in the census as a ‘shopwoman.’ Living with the family was a draper and milliner from Leeds by the name of Edith Miles, nine years older than Ada. The next time I find Ada she’s still living with her parents and Edith but they have moved to Market Street where they occupy two houses, and comprising a drapers/milliners/tailoresses shop. Ada was 36 when she married Edgar Harwood, just a year older than her. It must have been presumed by friends and family that she was a confirmed spinster by that time. After their marriage the newly weds moved to Hurst Dene. Ada’s widowed mother, 71, moved in with them, and Edith Miles, Ada’s business partner also continued to live with them. Today Hurst Dene is a five bedroomed semi detached stone house in the Birchcliffe area of Hebden Bridge, the posh end of town with its Victorian villas, and is grandeur is testimony to Edgar’s successful business as a shuttle tip maker. From Ada’s birthplace I retraced my steps along the banks of the River Calder and from the centre of Hebden Bridge I climbed the steep hill of Birchcliffe. Hurst Dene is situated on a corner plot almost opposite the former Birchcliffe Chapel, now the repository of the Hebden Bridge archives where I’ve spent many hours in the course of my research. As luck would have it the front door of the house was open. Looking past the stained glass panels set into the door I could see a grand piano in the room beyond the hall. I called out a friendly ‘Hello’ and soon found myself chatting to a young man. He knew all about Ada’s story and her time at Hurst Dene and it wasn’t until later that I realized that he is one of the organists on the rota at Heptonstall church and so I recognized his name. For the Harwoods to have lived in such an impressive house at the end of ‘snob row’ told me a lot about their wealth and status in the community so I set out to find out Edgar’s story little thinking that it too would feature in my Untimely Deaths project.

Leave a Reply