Winter was turning into Spring. At least the calendar told me so though I was somewhat skeptical since the temperature was in still in single digits. But at least it was sunny as I set off to find the appropriately named hamlet of Winters, once the home of John Gibson, the founder of a dynasty of innkeepers, spanning several generations. The Gibson family, who had married into the Whitham family has some of the most colourful characters in my family’s history but also some of the greatest tragedies. In 1834 at the age of 57 John Gibson was a shopkeeper and retailer of beer in the tiny hamlet of Winters, a small community that had grown up around a cotton mill, and appropriately named for my chilly but sunlit excursion in 2020. John was an important man in this sparse community of around thirty people clinging precariously to a steeply sloping hillside above the Calder Valley between Hebden Bridge an and Todmorden – for not only did he run the only shop in the village but he also had a license to sell beer. He’d moved up to this remote spot after twenty years of being the landlord at The Bull Inn close to the centre of Hebden Bridge and it was at The Bull that John and his wife Sarah Crabtree had raised their four children, two of whom were to become innkeepers themselves and one was to marry an innkeeper. To assist me in arriving at the start of my walk I caught the little Zippy bus up to Blackshaw Head, only three miles from Hebden Bridge, but three very steep miles and the bus laboured, puffing and panting, as it climbed the 800 ft to Badger Lane.

It’s a road well travelled by me for its wonderful views as it hugs the contour. Its name always brings a smile to my face. I’ve taken many photos of bleating lambs and mooing cows, and even a llama, but there’s never been a badger in sight. To find the tiny hamlet of Winters from Dry Soil I needed to find Marsh Lane, a well used bridle path on the north side of the valley, heading down towards the river Calder. Dry Soil, Marsh Lane and Winters. Hmm. The impact of the landscape and seasons was impossible to ignore.

I found a path that I thought was the correct lane but there was no road sign to confirm my suspicions but a man walking towards me along Badger Lane was just turning onto it with no hesitation and so I called out, “Is that Marsh Lane?’ “Yes.” I crossed over the road. “Do you mind if I join you for a little while? I’m looking for Winters Mill.’’ He knew the place and so we followed the path down towards Winters together. “I’ve always wanted to move to Hebden but my wife finds it depressing,” he confided in me.

I didn’t anticipate being able to locate the precise house that had been home to the Gibson family in the 1830s but I knew the view from the village would not have changed and I was looking forward to getting a feel for the remote location they’d called home. Winters Mill had been built in 1805 though virtually nothing remains of it today. The mill was both a spinning mill and a weaving mill. Originally it had been water powered and so I hoped to find the mill pond where water would have been stored and used to power the machinery at dry times of the year. Indeed, the first evidence I found that I’d actually arrived in Winters was the very pond, today shining a luminous green with its covering of duckweed.

Though now surrounded by a well kept garden the pond appeared to stretch to the very back doors of the cottages. I followed the lane around to the front of the cottages, neatly labeled ‘Winters Cottages’ as if for my benefit. At that moment a car drew up beside me and its owner rolled down the window. “Can I help you?” I explained my presence and she was very helpful. “We’ve just bought the end house, but haven’t moved in yet. Would you like to come in and see it?” I didn’t need to be asked a second time because this could easily have been John Gibson’s shop and beer retailing business listed in Pigot’s commercial directory of 1834.

We entered a house that was delightful in its preservation of original features. The interior walls had exposed stone and the rooms retained their stone flag floors. The ceilings were not more than 6’6” high and the stone fireplaces were intact, though they now had stoves inset. The lady took me into her back garden and within 6” of the back door was a small gully running with fast water over which a simple stone flag led into the large garden, half of which had obviously been the mill pond. An old water pump remained at the side of the pond. The cottage had been built around 1730 so even if John Gibson did not live in this cottage he would have known it well. As I took my leave the lady pointed me in the direction of the site of the mill. I slipped and slided away down the leaf covered cobbles knowing John and Joshua must have traversed these very stones.

When the mill was purchased by William Horsfall in 1830 he converted it to steam power to increase productivity and thus be better equipped to cope with competition from other manufacturers and it must have been around this time that John Gibson moved his family to Winters. Perhaps he wanted to take advantage of the anticipated increase in the population that the steam powered machinery would bring. He was closely associated with the mill, indeed his very livelihood depended upon it in the form of customers who were mill workers and when, in January 1834 some of the mill machinery was to be auctioned it was John’s son Joshua who arranged the viewing. The older part of this spinning mill used mules to spin yarn and the newer part contained looms which wove fustian cloth and so by 1842 the mill was capable of turning raw cotton into finished cloth having facilities for carding, spinning and weaving. Sateen, a mock silk made from cotton, and dimitie, a cotton cloth featuring raised woven stripes or checks used for making for dresses and curtains were manufactured here. As I stood on that remote hillside I found it bewildering to believe that this mill was said to be the largest manufacturer of sateens and dimitie cloth that was sent into Manchester to be distributed around the whole of England. In the 1841 census 32 men, women and children were listed as living in Winters, all but one, John’s son Joshua (listed as a farmer) working in the mill. I came upon a detailed inventory of the various rooms of the mill showing the extent of the operation: scutching room, card room, throstle room, three mule rooms, taking in room, counting house, smithy and mechanics shop. The mill even had its own school educating children from the hamlet and the surrounding hillside farmsteads– useful for Joshua’s 5 younger children while the older three, then aged 15, 14 and 12 were already employed in the mill. I tried to imagine life here in the 1830s when Winters was a tiny but bustling community with children going to school, people working in the mill, and shopping at Joshua’s shop cum beer house. Of all these once busy places of cloth making only a picturesque stone arch with initials and date carved above remains for when the mill went bankrupt in 1880 as the export of slave-grown cotton from the United States dried up. I learned from local historian Ann Bennett who used to lived in one of the cottages that the mill buildings were completely dismantled and sold for stone which was then used to build houses on King Street in the valley.

Another section of the inventory gave a more personal view of community life in 1842 as it listed farm animals and implements: Old white cow, red and white cow and roan cow, the new cow, old stable manure, bay mare, shaft and trace, general farming utensils and 3 stable buckets, 2 pack carts, box tubs, lumber, wheel barrow and hand barrow, 2 water tubs. 8 The beer cellar contained 10 ale barrels, racking of barrels, pots, cooler and 5 black bottles valued at £1.18s. When John died in 1837 his son Joshua had taken over as the shop keeper and beer seller at Winters, and he also ran a farm and was a butcher. Surely then, the beer cellar with its contents and the farm animals and implements listed in 1842 must have been Joshua’s. Joshua’s son John, aged 15, is a carter and so the bay mare with its shaft and trace would have been for his use. Meanwhile on being widowed his mother, Sarah, had moved back down into Hebden Bridge and had returned to the Bull Inn as innkeeper, along with her daughter Sarah. On his mother’s death in 1845 Joshua moved back into the valley and took over the pub whilst continuing to farm five acres, and slaughtering the animals for his butchering trade.

It was time to head down into the valley following Joshua and Sally’s footsteps. I’d checked with the locals that my planned route was easy to follow and I wasn’t going to find myself sliding down the hillside on my bottom, or needing to climb gates. Winters Lane is just about negotiable for vehicles but it ends at a five barred gate and turns into a tiny track called Dark Lane.

This was more like Dark River today but my new hiking boots were up to the task. Dark Lane led back onto another lane that was just about passable by car, though very, very steep. Bags of salt were stationed every ten yards for icy weather. The sound of traffic along the Calder Valley rose up to me and the whistle of the train blended in with the birdsong from time to time.

It reminded me that it was the coming of this very railway line in 1839 that meant that Winters mill could more easily obtain raw cotton from Liverpool and send finished goods to Manchester much quicker. Eventually the lane led to Rawtenstall Bank, another very steep road with several switchbacks. Though slippery with wet leaves I decided to stick to the road and not take the short cut down a well worn flight of stone steps neatly signed Cat Steps! Reaching Hebden Bridge I passed the site of the now demolished area of town known as Bridge Lanes, Joshua and Sally’s home in 1844. The densely packed community of Bridge Lanes at the west end of town was once a conglomeration of streets, almost literally on top of each other connected by several flights of stone steps. The whole development was demolished in the 1960s and apart from the stone staircases nothing remains of this once bustling part of town. Almost adjacent is the former Bull Inn, now a private house, where John, his wife Sarah and his son Joshua and daughter Sally had been landlords for over thirty years.

A lady was refurbishing the front door and so I paused to ask if I was correct in thinking that this had been The Bull. It had, and she explained that under normal circumstances she would have invited me in when I told her that one of my ancestors had lived there. It was only then that I realised that I’d actually been inside this building before. It’s now the home and studio of a wonderful artist, Kate Lycett, and I’d visited her in her home studio during the town’s Open Studio event the previous year. At the time I’d no idea that the building had been the home of my ancestors.

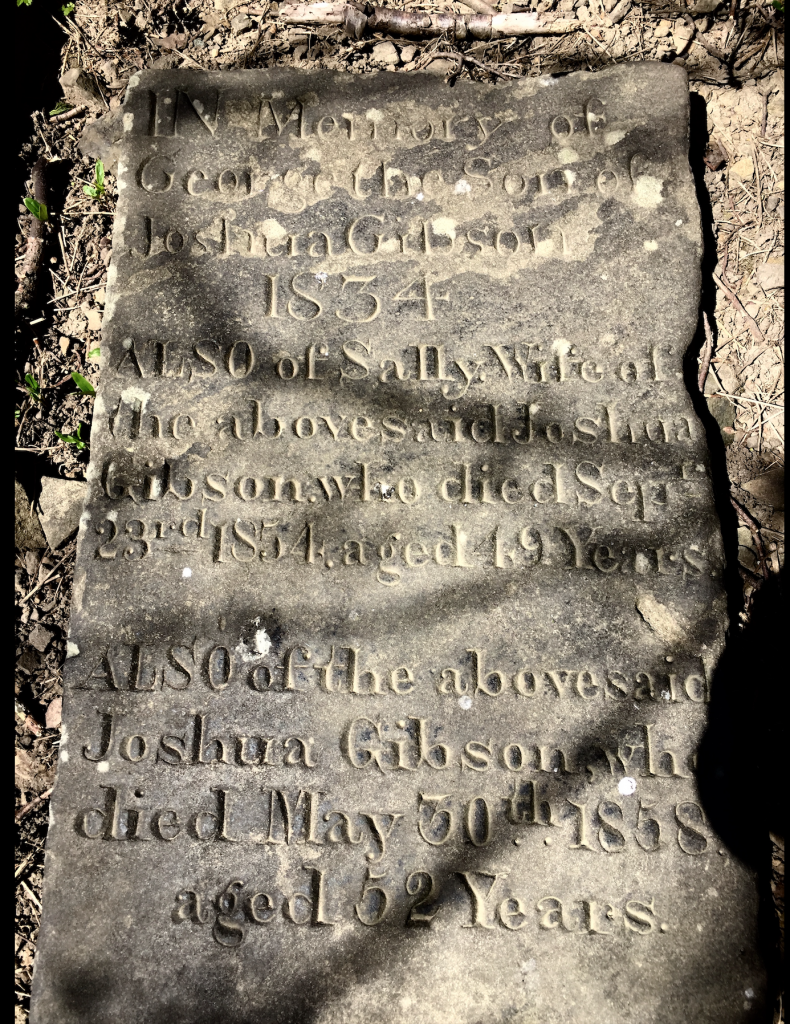

Joshua operated the Bull Inn for more than ten years but in 1855 at the age of 49 he gave up his alcohol license soon after his wife Sally died. Joshua continued as a butcher, living at Bridge Lanes, but I was shocked to read that the following year he hanged himself on May 30th, 1858 and was buried at Heptonstall church three days later. The article in the Leeds Intelligencer reads: ‘On Sunday afternoon last, between three and four o’clock, Mr Joshua Gibson, butcher, of Hebden Bridge, was found dead in the chamber of the house, deceased having hung himself. The cord by which he had been suspended had broken, but not before he was dead. Gibson had been drinking for some days previously.’9 There’s a note in the burial record, written by the minister at Heptonstall church ‘he hanged himself in his slaughterhouse.’ Apart from the comment about drinking heavily in his final days we don’t know why Joshua took his own life in such a deliberate manner but there are many many accounts of suicides by hanging in the local newspapers of the time. His eight children survived him. One of them was Stansfield, who was nineteen at the time of his father’s death.

The pub closed its doors for the last time in the 1970s when much of the town was abandoned. On 1st January 1978, fire broke in the former pub out and the bodies of 2 men (possibly squatters) were found in the attic of the empty building.

Leave a Reply