I’d set up a meeting with David Gelsthorpe, curator of The Earth Science Collection at the Manchester Museum, to view Samuel Gibson’s collection of fossils and flora. I’d been looking forward to this opportunity for a couple of years – ever since I’d first discovered online that one of my ancestors was a famous collector of fossils. I remembered my own first foray into that interest: my mum had taken me Youth Hostelling for the first time, to Slaidburn Youth Hostel, and we’d taken a walk around Stocks reservoir, where I’d found fossils corals, showing me, at first hand, so to speak, that at one time this part of Lancashire was a tropical seabed. That blew my mind. I think I was 11 at the time. I seriously considered becoming a paleontologist but my understanding of science was poor and by the time I came to do my ‘O’ levels I’d dropped the idea altogether and taken up music as my life’s work. When I left the U.S 18 months ago I placed a lot of my fossil collection in the garden, but I think some it it still remains in the storage unit in California. Some pieces I took to the Bolton Museum and was told they were fossil ferns in the shale/coal deposits. On a trip to the south of England with my mum and dad when I was 14, I was responsible for the planning and so a trip to Lyme Regis was high on the list of ‘must sees’ and I came home with many ammonites. Aust Cliff, under the Severn Bridge, also reaped rewards. Two books which remained on the bookshelf above my bed at Affetside were Fossils and Geology. I may still have the Fossils book.

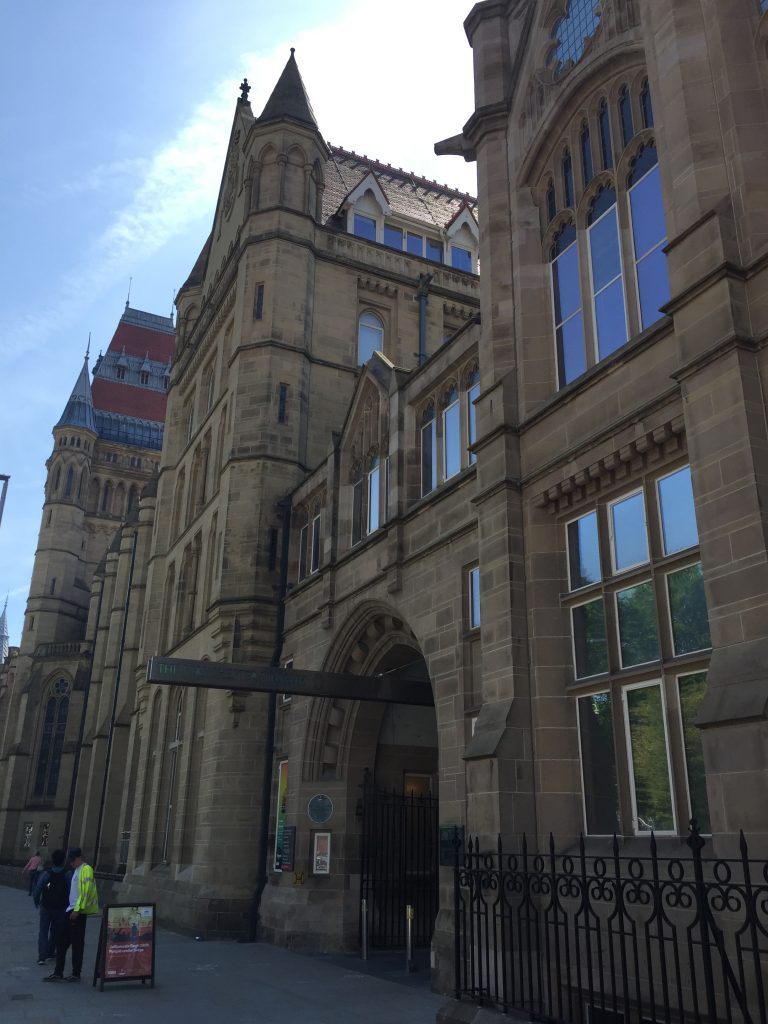

I was at Hebden Bridge station in plenty of time. For the first time this ‘summer’ I was wearing sandals and only had a cardigan, no jacket. Under a totally blue sky sporting plane vapor trails galore, the train arrived. I boarded. So did a dog and its owner. We sat down. The train didn’t move. The dog whimpered loudly. The dog began to bark – very loudly. Still the train didn’t move. The dog’s minder apologized: we’re only going to the next stop. Eventually after 20 minutes the guard told us that Northern Rail apologized, but he couldn’t tell us what was holding us up. i thought that perhaps there was a problem with the rails to our West, but incoming trains proved otherwise. After 35 minutes, during which the dog just about deafened me, we were told to get off the train, it wasn’t going anywhere, and the next train to Manchester would be along in 15 minutes. Fortunately from then on everything went according to plan. The barking, whimpering dog, did, indeed get off, thankfully (for it and me!) In Todmorden and the ride into Manchester was uneventful. I. Now had only 10 minutes to get to the Museum for my appointment. I checked the buses, ones you pay on, free ones, Uber rides in the locality, and eventually had to plump for a taxi which delivered me to the museum only 5 minutes b behind schedule. The building is a grand affair – Victorian architecture at its finest. It’s connected to Owen’s college somehow – where Anna spent a year when she was a student at Manchester uni.

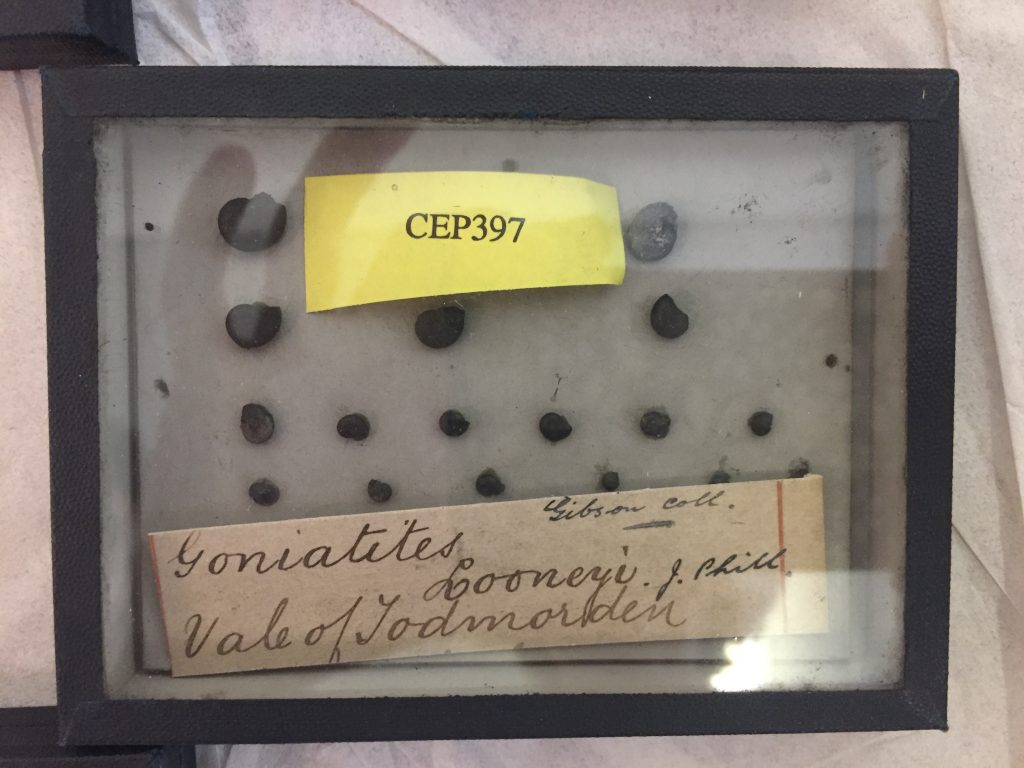

The girl on the front desk called David and soon I was following him behind the scenes into the depths of the museum. On a table Samuel Gibson’s fossil collection was laid out, all ready for me to view. I was impressed. My experience of people’s organizational skills in my area hit rock bottom yesterday when, on my visit to a prison, the leader of our group had forgotten to email one of our volunteers of details of the day. She’d even taken the day off work in oder to volunteer! So to see the boxes of fossils all laid out ready for my attention was wonderful. Many of the exhibits were ammonite-like creatures called goniatites, precursors of ammonites with less defined whirls on them. Some of them were no bigger than a pin head. I was fascinated by how Samuel had even seen these tiny fossils. Many were labelled in his own handwriting and included the location from where he’d collection them The shales of Todmorden were mentioned frequently, and to my amazement so was Slaidburn!

To think that these tiny fossils had possibly been on display in Sam’s pub/museum in Mytholmroyd between 1842 and 1849. I can’t really imagine that they would have attracted customers to his pub. To serious collectors they would have been very important. One goniatites is named after him Goniatites Gibsonii but it’s tiny, no larger than a 5pence piece. Some fossils were housed in tiny cardboard cylinders, less than an inch in diameter, that perhaps Samuel made himself. As I chatted with David about this collection I learned that he, too, lives in Hebden Bridge!

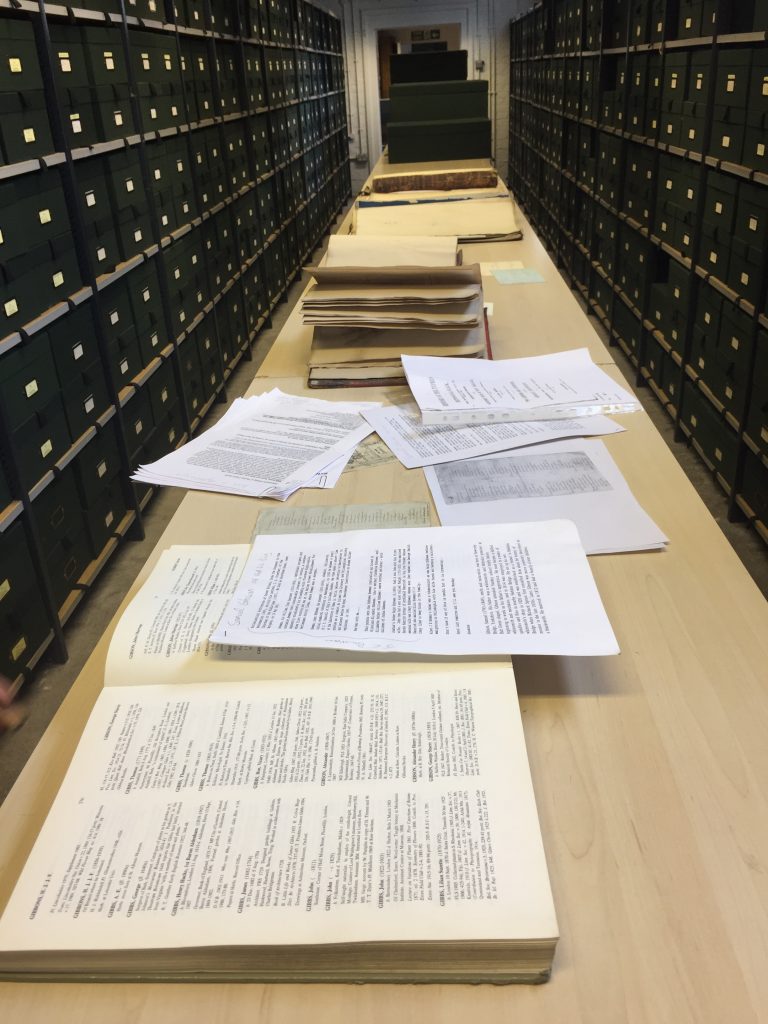

After taking photos and getting to hold some of the fossils myself David took me to meet Lindsay who is the curator of the Flora collection. We walked along corridors filled with deep green boxes which contain 650,000 specimens. Apart from Kew gardens and the British Museum in London Manchester’s collection ranks with those of Birmingham, Oxford and Cambridge in the size of the collection. I spent the next hour in the company of Samuel’s collection of plants as Lindsey Loughtman, Curatorial assistant, Botany, and her PhD student gave me their undivided attention.

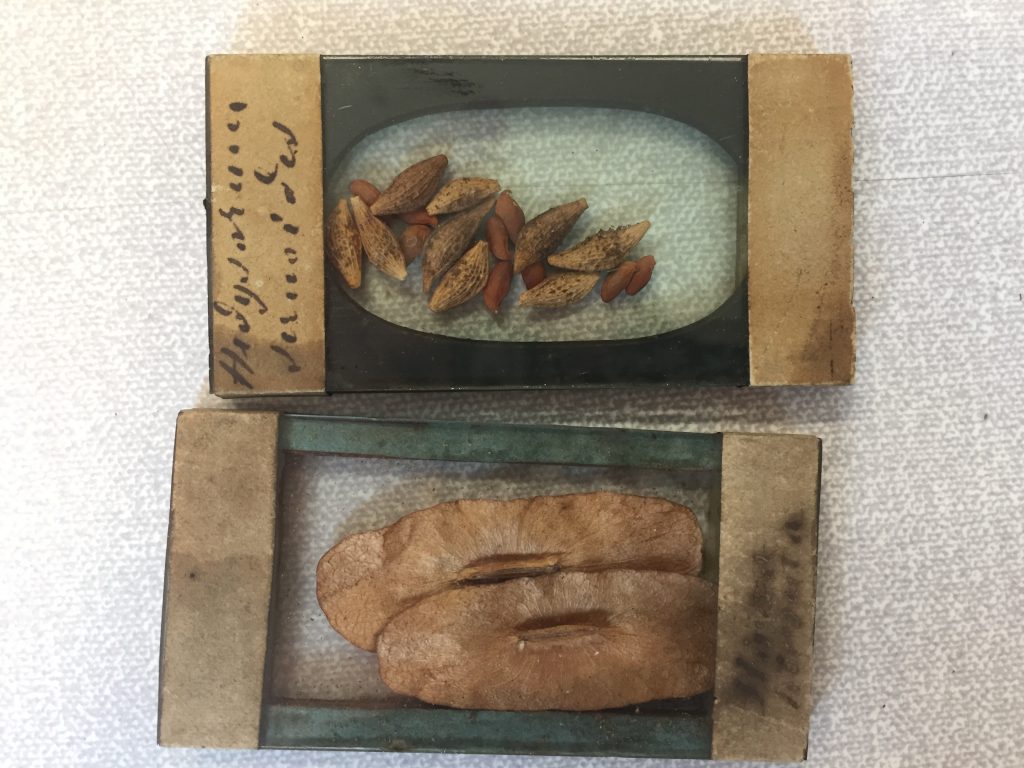

Lindsey had sent me an email: We have several thousand Samuel Gibson specimens, possibly more as we’re still cataloguing the collection. Around 2000 microscope slides of seeds, and 160 lichen, with fewer British wild flowers and ferns. There are three algae exsiccatae too.

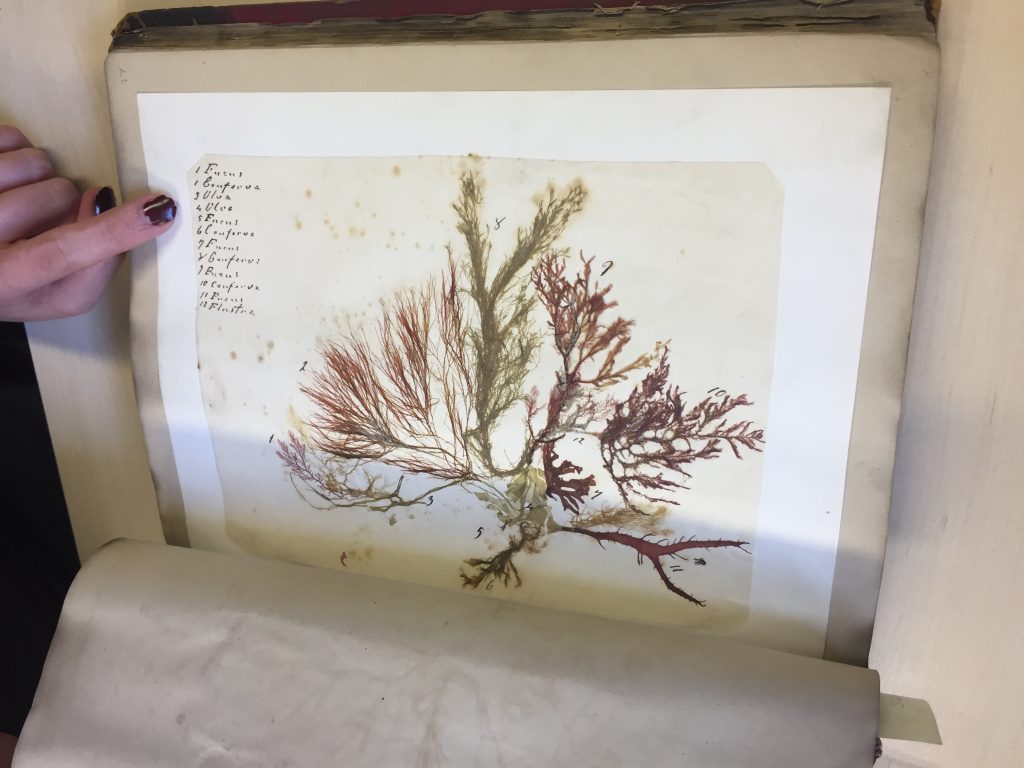

We were in a lovely sunny room and at the long table a few volunteers were working on preserving some plant collections – herbariums. I had thought that a herbarium was a place – like a conservatory – but it means a collection of plants, either pressed on paper and catalogued in books, or pressed between glass to make glass slides. I was told the amazing story of how, in 2016, a large red corrugated box was discovered in the the midst of the 650,000 specimens and Lindsay asked her assistant to clean all the slides (8 boxes each containing 150 slides) and catalogue them. This took her from September til December. Along with the slides there are small glass boxes in which there are seeds which can move around in the box. Then, already set out on the long tables, ready for my perusal were Samuel Gibson’s books of pressed mosses and lichens. Each was labelled in his own hand, and again, like the fossils, one was named after him! The museum had obtained at least some of the collection from the Royal Museum and Library at Peel Park in Salford, so I need to find out more about that. It was wonderful to hold the slides with his tiny handwriting identifying the specimens. It reminded me of the juvenile Bronte books written in the tiniest of lettering. Many of the names of the specimens were printed and Lindsay suggested that these labels had been cut from books and/or magazines. I wondered how Sam’s dates filled in with those of Mary Anning, the fossil collector from Lyme Regis whose discoveries turned the idea of God creating the world and all living creatures in 6 days on its head. I had noticed that at the end of the two papers that Sam had appended too the Heptonstall Slack typhus epidemic that he makes reference to God’s world, demonstrating his faith.

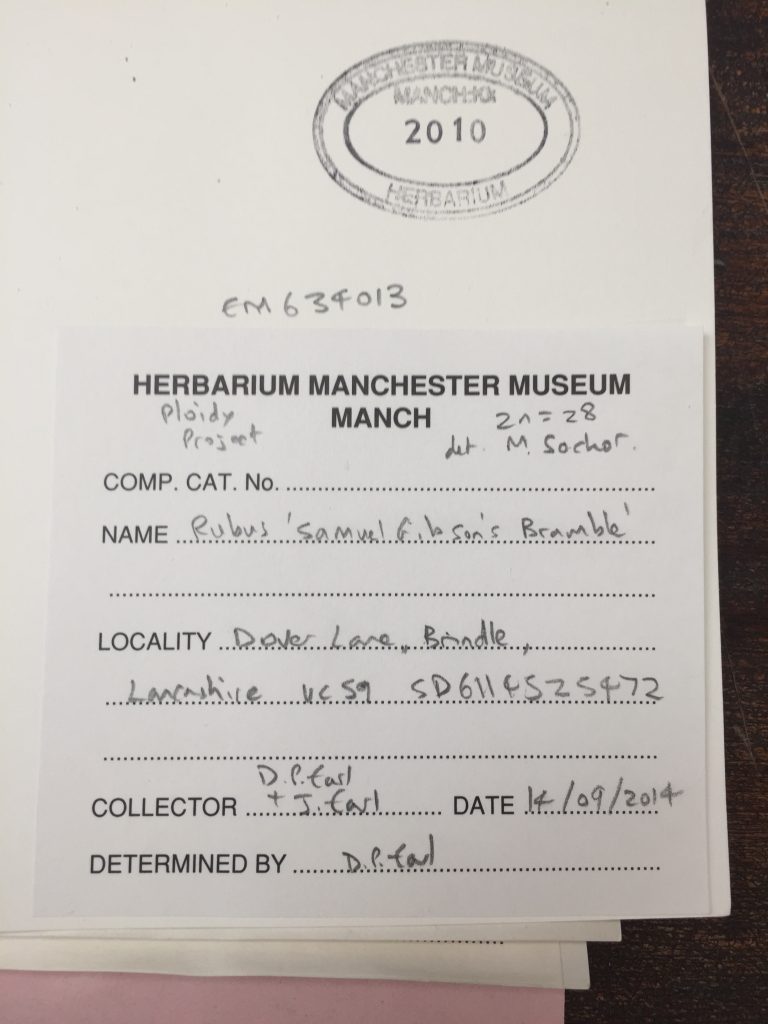

After lots more photos I was taken to meet Dave Earl, one of the volunteers, who recently discovered a previously unnamed raspberry bramble. He’s had its DNA tested by someone in the Czech republic and lo and behold Dave had named it in honor of my ancestor – Gibsonii. I suggested it might be appropriate to plant it on Samuel’s grave if we can find it under the years of leaves and brambles at Butts Green Chapel. Wouldn’t it be amazing if that particular bramble was actually already growing in that cemetery? Dave travels all over this area in search of specimens and so he’ll be heading out to Warley sometime soon!

11th May 2020 at 6:37 pm

Having read this I thought it was extremely enlightening.

I appreciate you finding the time and effort to put this informative article together.

I once again find myself spending way too much time both reading and posting comments.

But so what, it was still worthwhile!