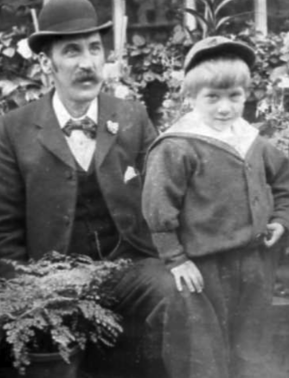

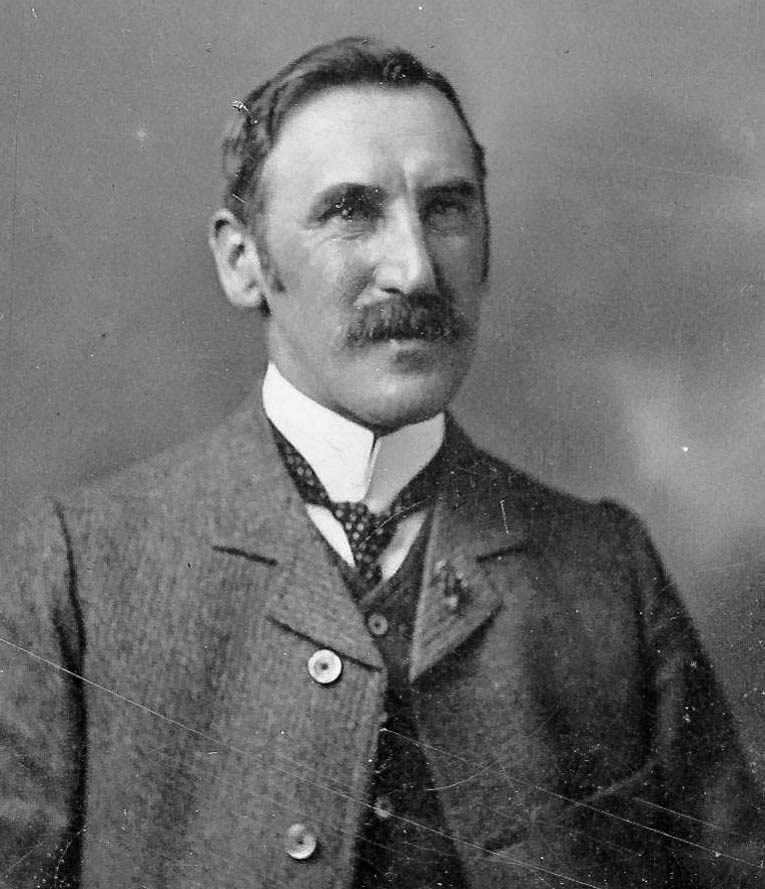

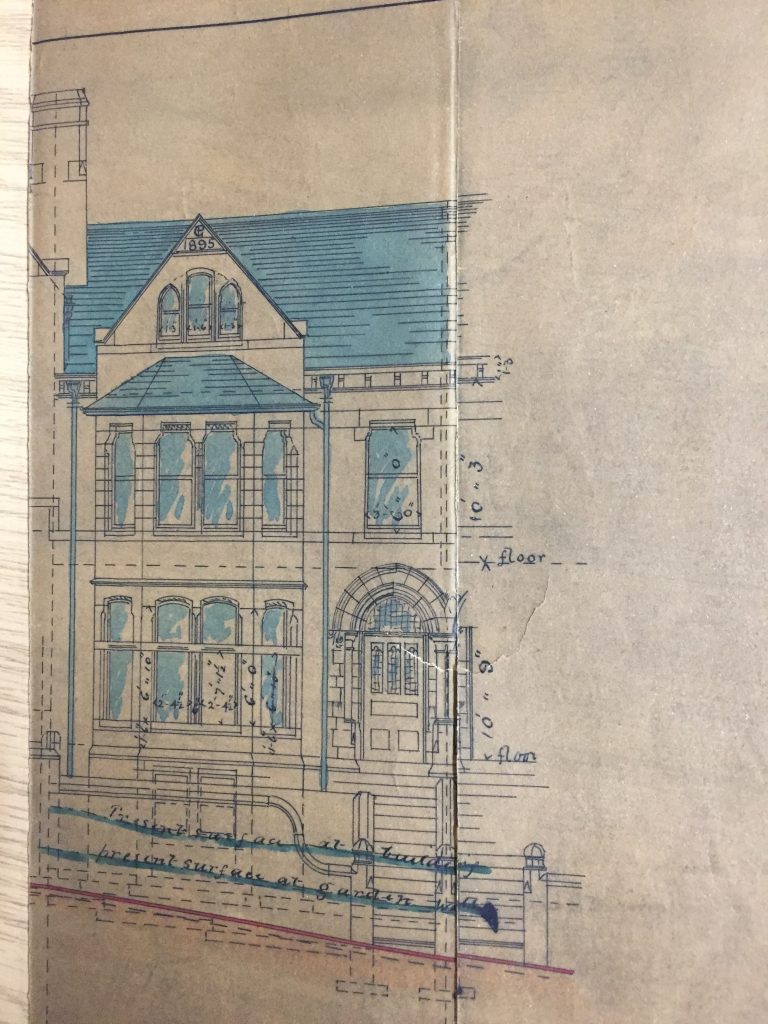

WALTER EDWARD MOSS 1888-1940 Abraham’s fourth child, Walter Edward first attended Stubbins Junior School, just steps away from Brooklyn but whose position halfway down the incredibly steep Birchcliffe hill appears to defy gravity.

He was subsequently sent to a boarding school just outside Leeds. The name of Fulneck Boarding school may not be as recognisable as Eton or Harrow but it can number in its role both a future prime minister – H.H. Asquith, and a future Avenger – Diana Rigg. As would have been expected Walter subsequently joined the family’s thriving fustian business. Germany was the centre of new advances being made in the development of synthetic dyes and so, in 1906, Walter went to Germany to learn dyeing at the Leopold Cassella Company of Frankfurt, a company which, by the outbreak of the war had 3000 employees and was the world’s largest producer of synthetic dyes. On leaving Cassella Walter was presented with a gold watch which is still in the family’s possession. I obtained a photo of it from Walter’s son Geoff and the inscription reads “In commemoration of your stay at the factory of Leopold Casella & Co Frankfurt am Main.”

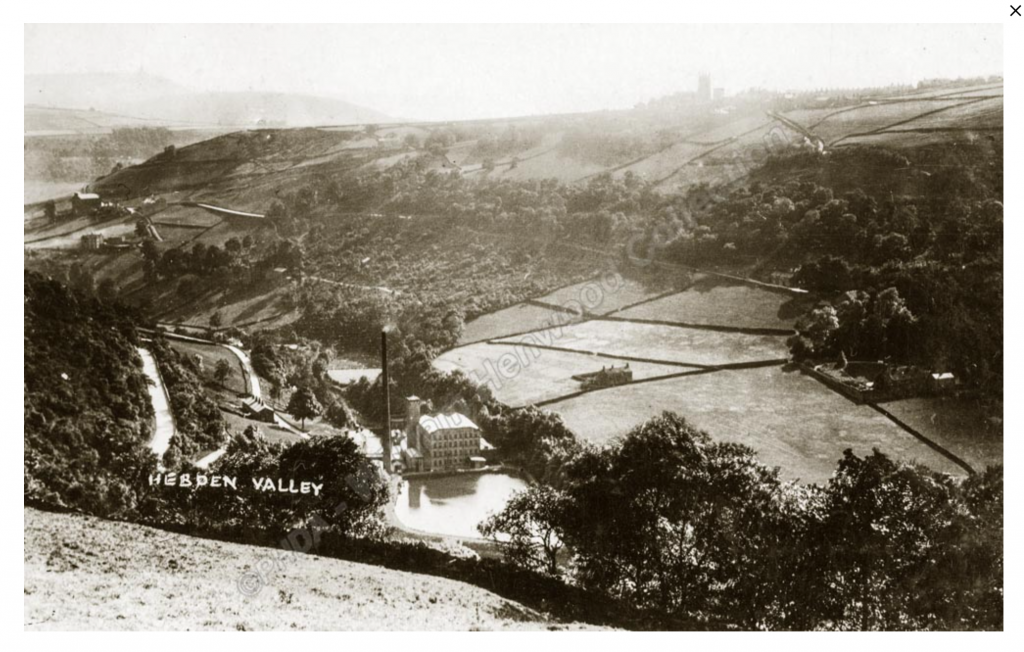

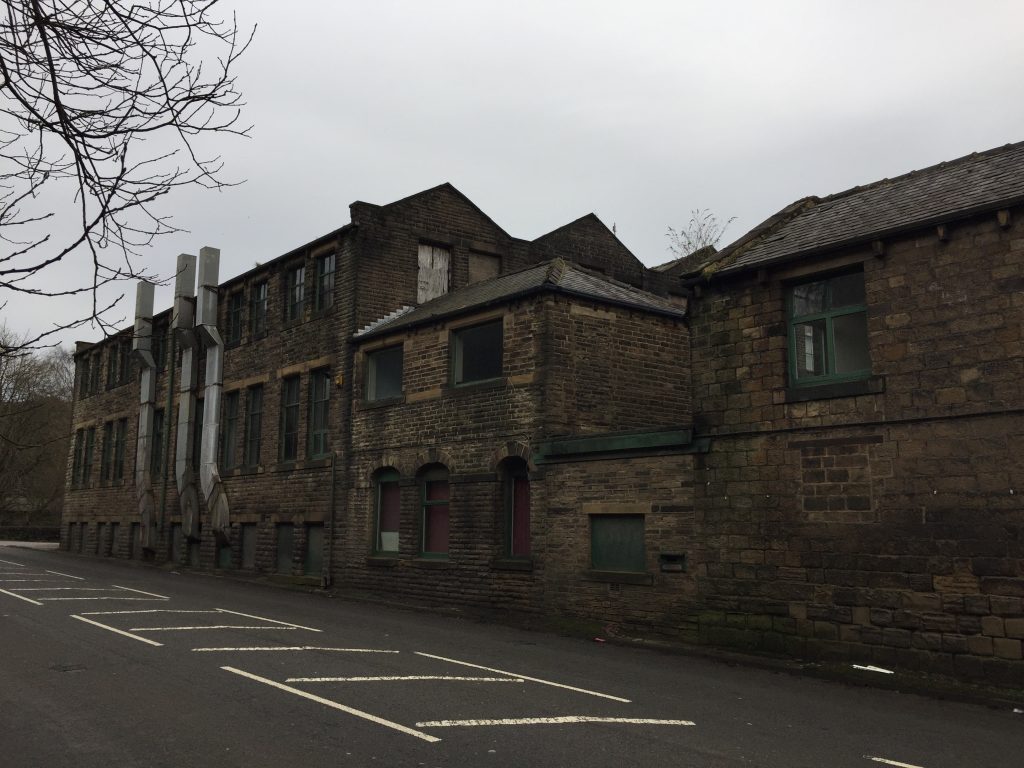

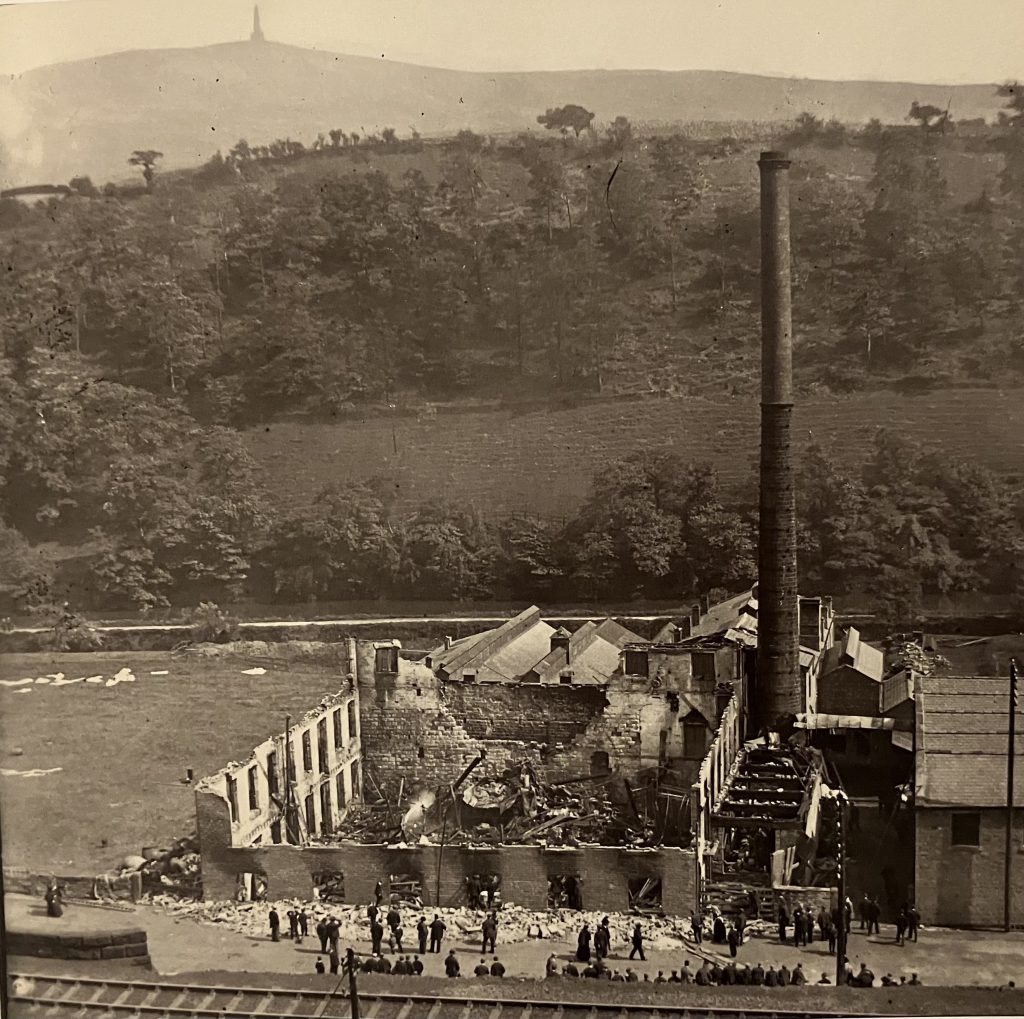

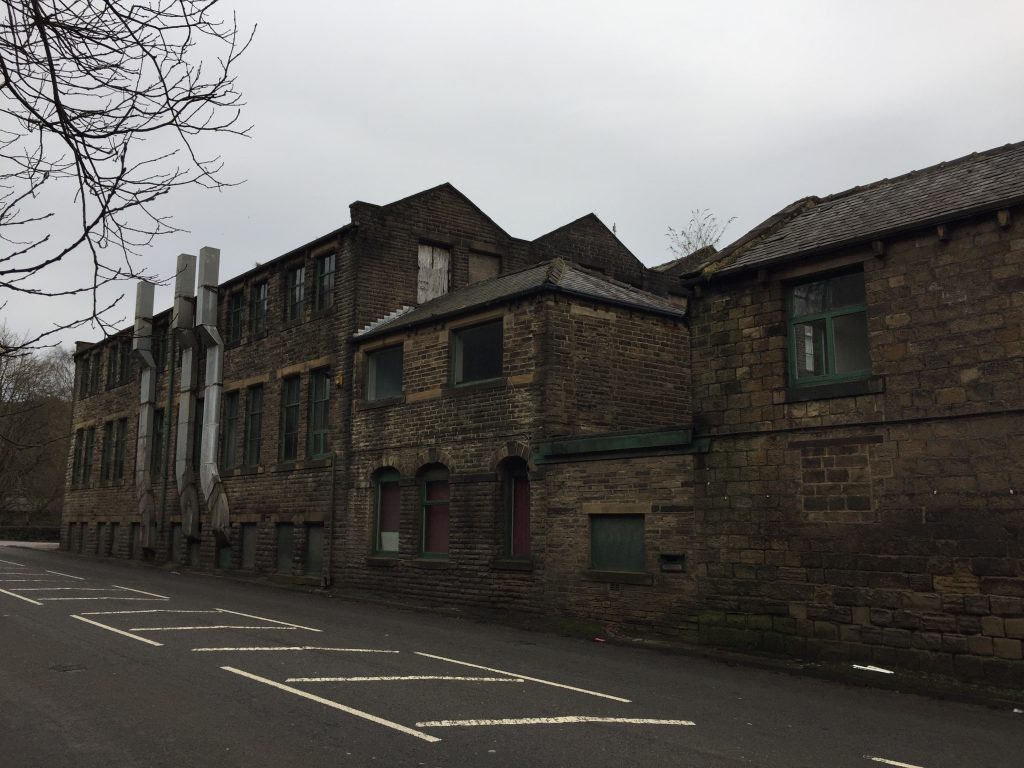

By 1904 the Moss family was running Lee Mill for weaving, dyeing and finishing and it was there that Walter worked on his return to England becoming the head dyer in the Moss textile company by 1911.

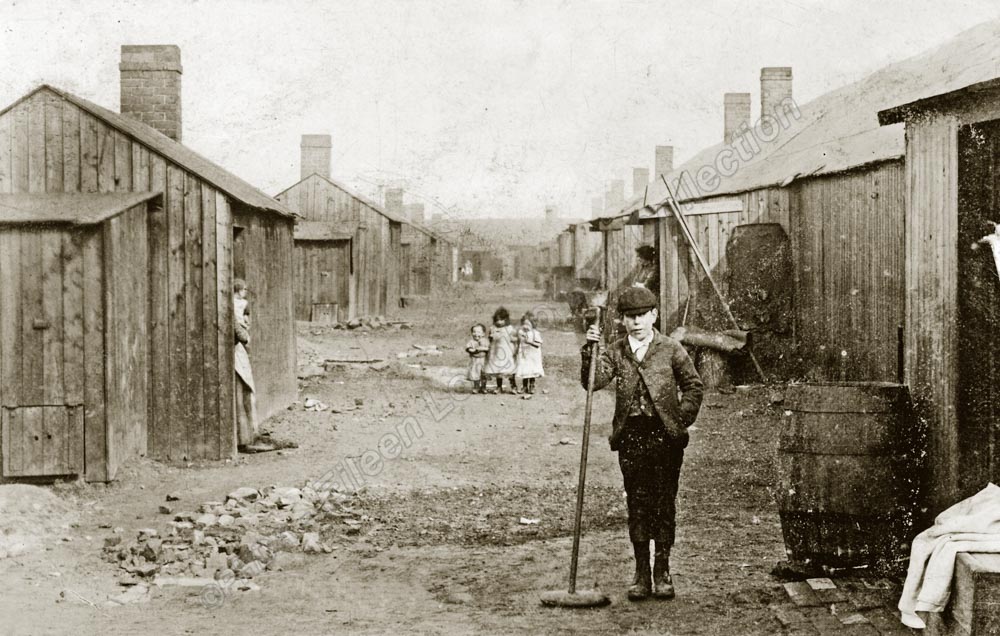

Initially the weaving looms were housed on the fourth floor of the mill but Mrs Moss read a novel by Thomas Armstrong,‘The Crowthers of Bankdam’ about a mill owning family who had looms on the top floor of a mill.50 Tragedy struck when the mill collapsed under the weight and it was only then that the Moss family built a separate weaving shed. The Moss family also had an expansive dye works at Bridgeroyd situated conveniently for the workforce between Todmorden and Hebden Bridge. It was managed by Walter’s uncle, Fred.

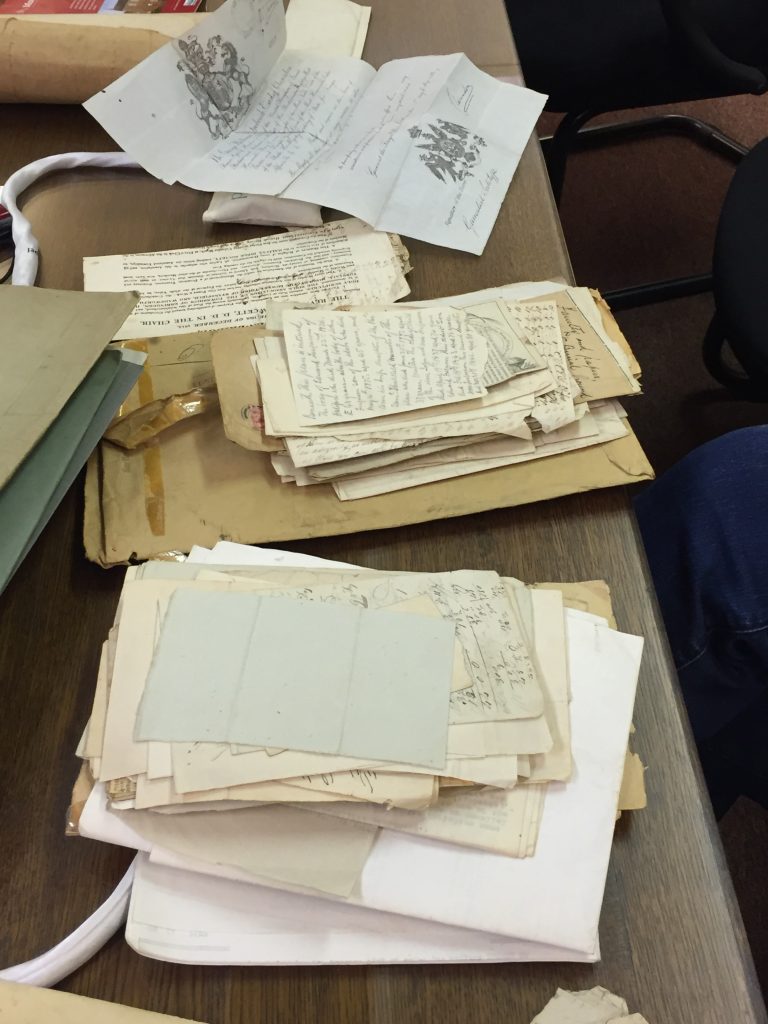

When not at work Walter and his brother Reginald were heavily involved with the Caldene Hockey Club for which they played until 1914 when they were called up for military service. Crowds gathered to see local territorials march off to Halifax through Hebden Bridge and brass bands gave the recruits a true Yorkshire send off. But today there was no brass band accompanying my walk back into Hebden today. Walter served in France throughout the war and Reginald was posted to India. In April of 1916 he wrote a letter home from somewhere undisclosed in France, describing vividly his first hand experiences of aerial combat. “On Monday I had the pleasure of seeing a German aeroplane brought down. The guns that brought it down had only fired 6 shots when down came the aeroplane with such a smash. Needless to say the two Huns were killed outright and the machine was like so much old scrap iron. There was a great rush to the place for souvenirs, and hundreds of soldiers collected round but another aeroplane came and tried to drops bombs on the crowd. Luckily he missed his mark. They were both officers in the aeroplane one being a colonel and the other a major so it was a fine bag. . . Last night we were wakened up suddenly by a hooter and bells ringing. It was a warning to be prepared for a gas attack. We closed the windows and got our gas masks ready for use. However, when the gas came along it was very weak. But many put their helmets on. The madame and children at the house where we stay got the ‘wind up’ properly and were walking about all night with their helmets on. The weather is beautiful and hot now and we all wish we wore kilts. The Scotties are all right this sort of weather. I understand Blackpool has been very busy during Easter.” In another letter “I have had a letter from Reggie and he seems all right in India, and got settled down to the different life. I should not mind being out there. Fritz sent a few shrapnel shells over last night and this morning. One burst over the building a few of us were in and the slates came rattling down on top of us. However, nobody in our lot got hurt but a few fellows lower down the street were wounded.”

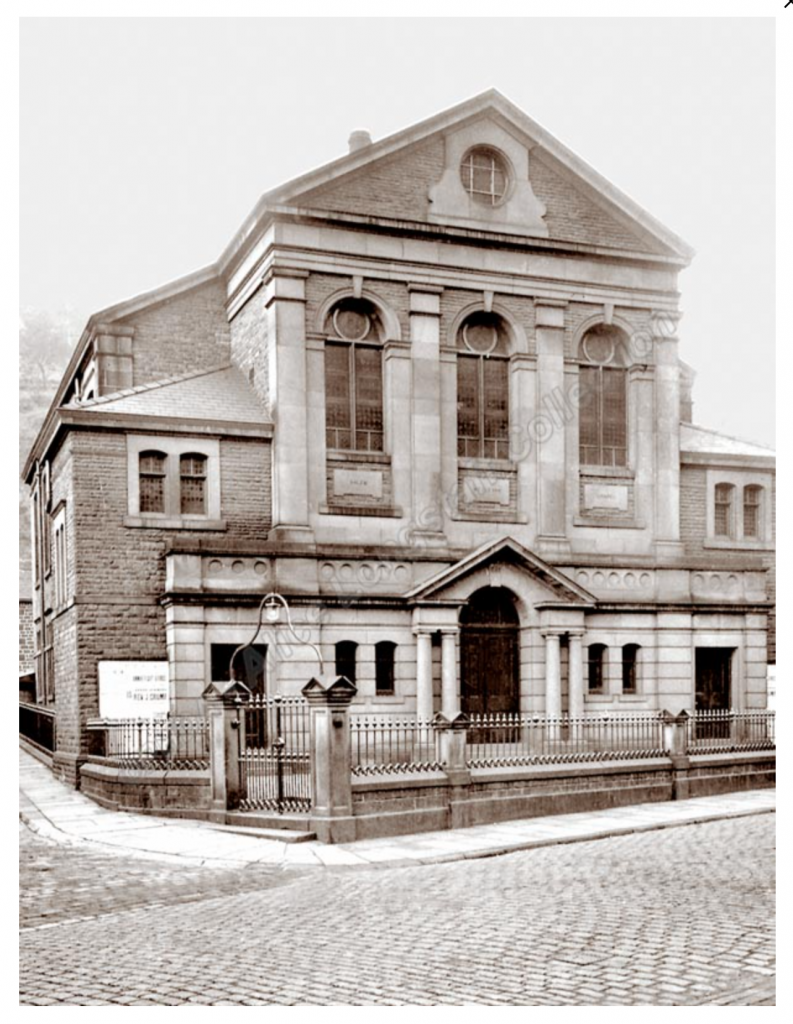

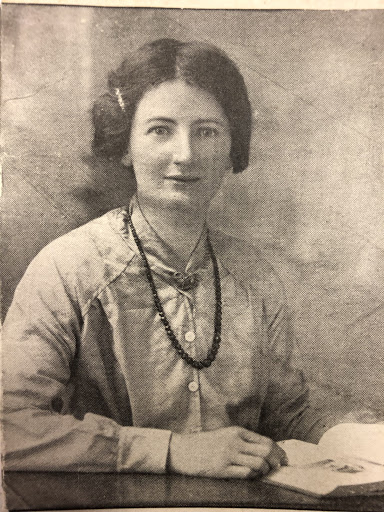

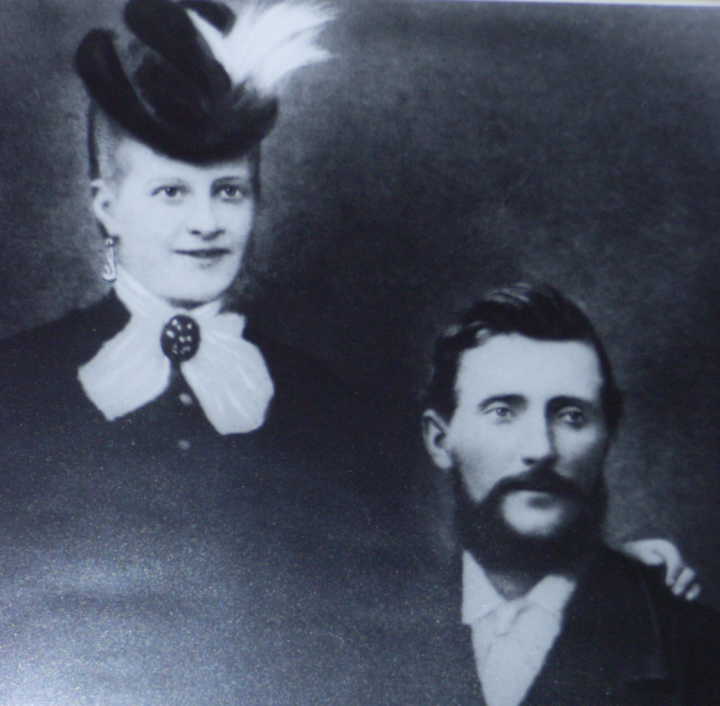

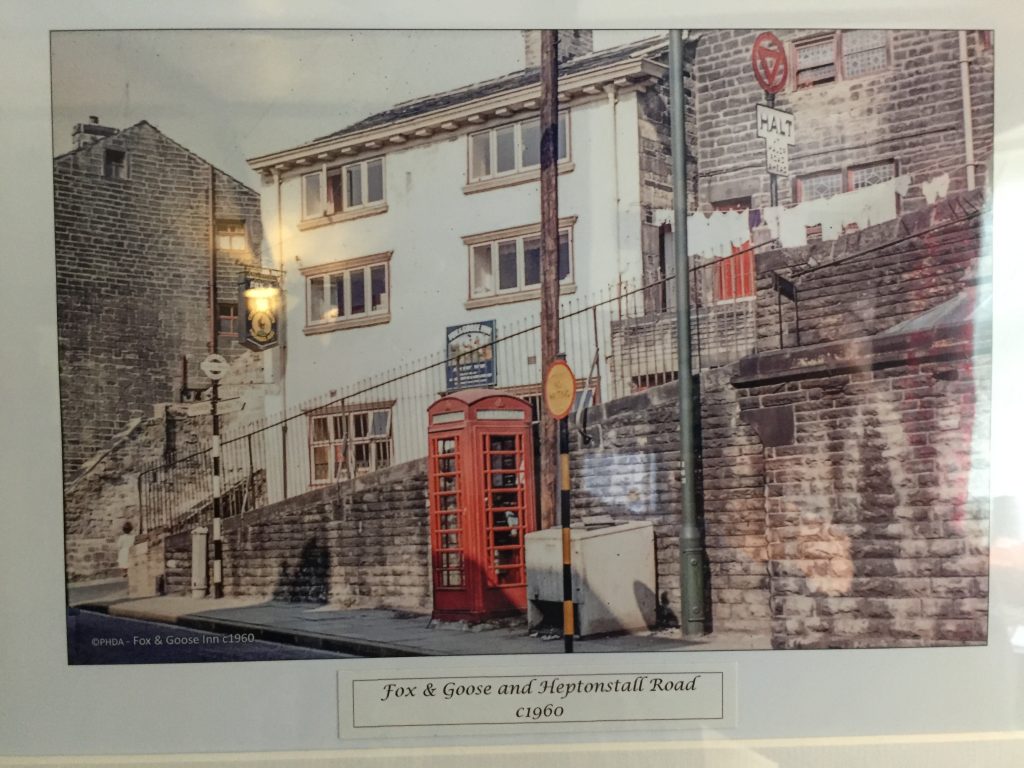

The juxtaposition of his lighter comments about holidays in Blackpool and Scottish kilts with tales of being gassed and bombed is poignant. His son told me that his father suffered from the effects of a gas attack. My own paternal grandfather did too, but as was common, such injuries were very rarely spoken of within the family. And his glee of the bringing down of the German plane reflects the attitude of wartime combat. How ironic that he had spent time in Germany in 1906, learning the craft of dyeing from the experts. Living in a large detached house whose steep gables rise proudly above the serried ranks of terraced rooftops and only a couple of minutes’ walk from Brooklyn, was one of the leading business owners of the town, John Edward Wrigley, of Wrigley & Sons Painters and Decorators. His three daughters were all to make prestigious marriages, two to wholesale clothing manufacturers and one to a bank manager. One cold dark afternoon in January 2022 I met up with the wife of Walter’s great nephew. Liz Moss had already shared with me many photographs of the Moss family and she had something special to gift to me. It was a bible that had belonged to Phylis Wrigley, one of John Edward Wrigley’s daughters, signed in her own hand, May 17, 1908. She would have been 15 at the time, living with her family on New Road, unaware of her future life with Walter. The announcement of Phyllis’s wedding in the Leeds Mercury on January 23, 1919 says it all; The wedding took place yesterday at Salem Wesleyan Chapel. Hebden Bridge, of trooper Walter Moss, Brooklyn, and Miss Phyllis Wrigley, Beech Mount, representatives of two of the best-known families in the district.”

The Todmorden Advertiser gives a little more detail of what would have been a very grand affair. Headed ‘Khaki Wedding’ it reads: ‘The bridegroom is home on short leave from Germany so a short notice wedding! The bride was given away by her father in white charmeuse and Georgette with chenille embroideries. The bride had a wreath, veil and carried a sheaf of lilies and chrysanthemums. The luncheon was held at the White Horse Hotel and the couple honeymooned in London.’ Unfortunately both the chapel and the reception buildings no longer exist. After the marriage the couple set up home at Stoodley Range, Hurst Road, Hebden Bridge and it was only a ten minute walk from Brooklyn for me on this gloomy afternoon. I’d had a hard time locating this house since it’s since been renamed Nab Scar but today impressive stone gate posts taller than me with curlicue lettering carved atop an imposing wrought iron gate assured me that I was in the right place.

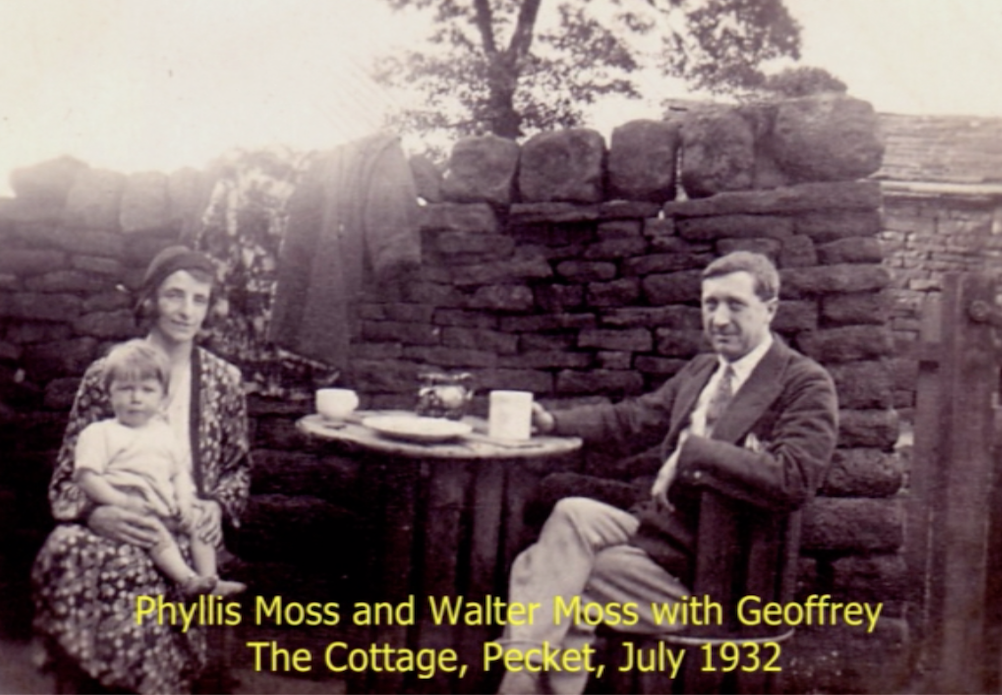

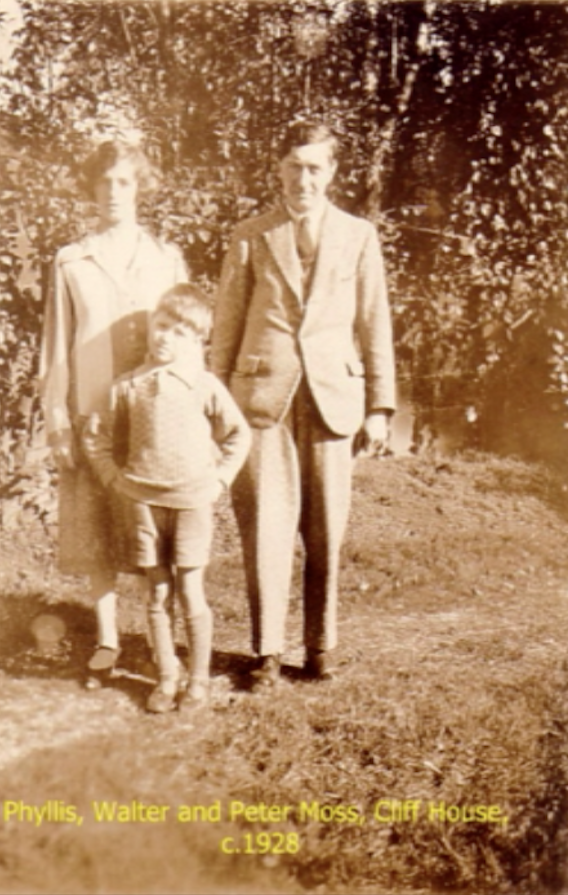

The gate was open so I peeked in. Recently it was put up for sale with the following description ‘ unique gentleman’s residence: six bedrooms. Rarely does an opportunity to rent such an exceptional residence present itself and the only true way to appreciate the accommodation is via an internal viewing.” Ah, if only. I secretly hoped that the current resident would come out and ask me my business, but no such luck today. I later learned that until recently it had been the home of Little Hill People, a business specializing in ‘Edgy Urban Tribal Fashion wear made from Fairtrade Handloom and Genuine Leather.’ I wonder what Phyllis would have thought of that. It was here at Stoodley Range that their son Peter Edward was born the following year. Only a couple of minutes’ walk from Stoodley Range is my next stop in the family’s story, Cliffe House where the family lived from 1925-1932, and where their second son, Geoffrey, was born in 1931.

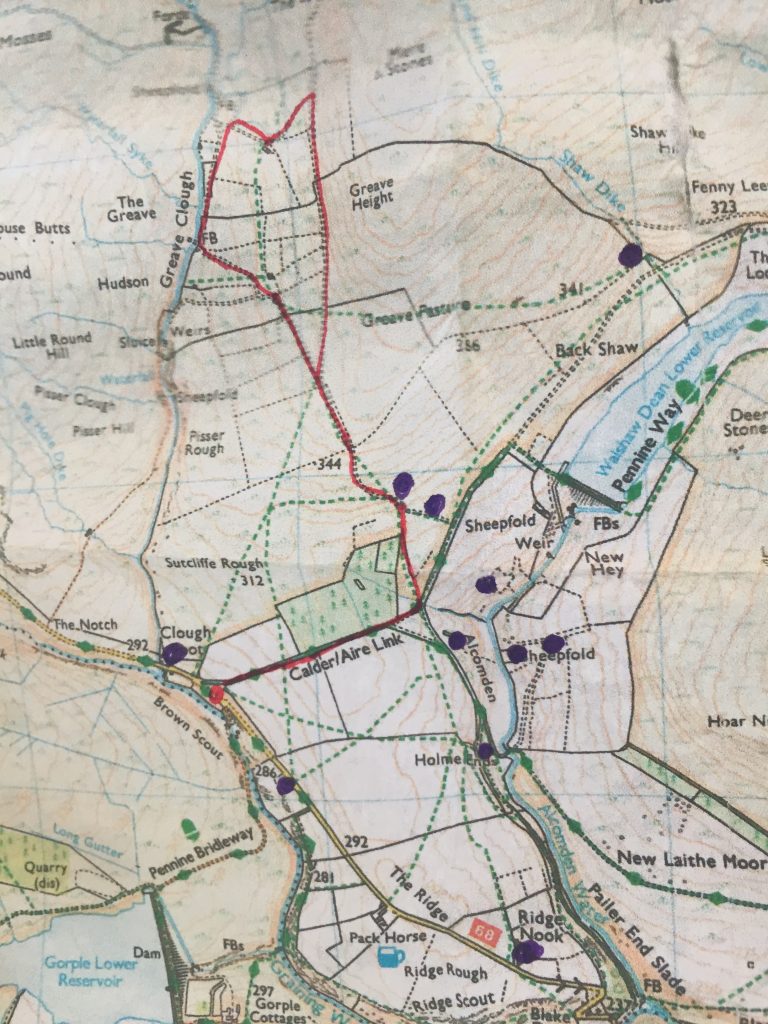

It was from Geoff, who passed away in 2021, that I gained much information about the Moss Family and in whose possession his mother’s bible had been. I followed a footpath leading through a dense wood which, on early maps is named John Wood, but by 1934 for some unknown reason it became Joan Wood. The path came out close to the entrance of the long private drive to Cliffe House. I’d passed these imposing gateposts several times during lockdown. One afternoon I’d even looked up the name of the house chiselled into the stone, Arnsbrae, thinking no, that’s where Cliffe House should be. What drew my attention to the opposite post this rainy afternoon I don’t know. Perhaps it was the sodden stone reflecting the light differently but there, etched into stone but only just discernible were the words Cliffe House.

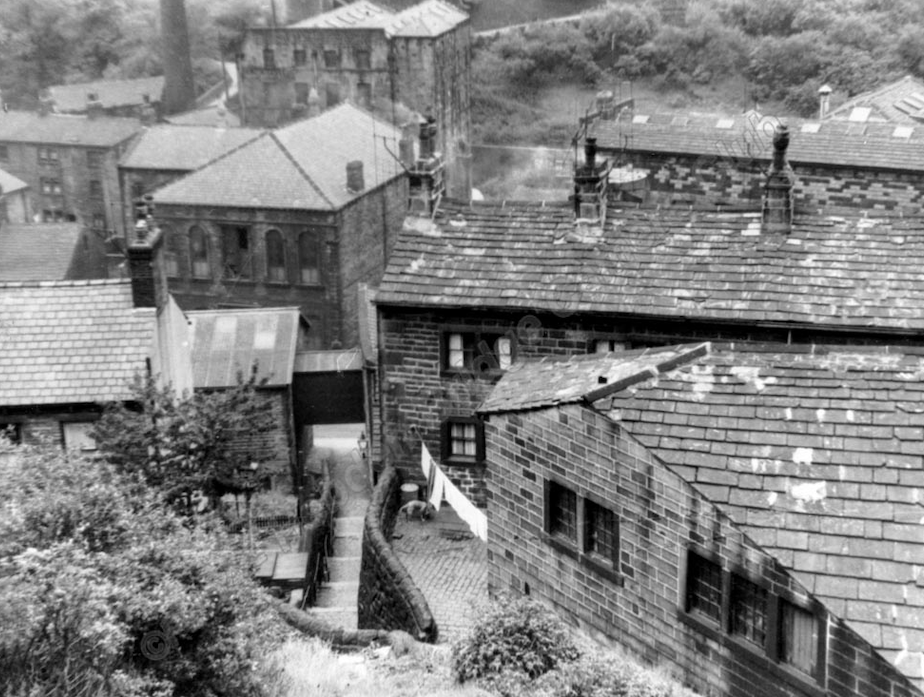

I followed the wide drive up and around the hill. This area of Hebden Bridge is called Wood End, and I verily wished that the wood would end so that I could catch a glimpse of Walter’s former home. I came at last to the end of the drive and the house came into view but it was tucked away behind more gateposts and walls. The front of the house was facing away from me, with a bird’s eye view of the town below. Just visible high above the town, peeking out from the trees I could just make Lily Hall, its weavers’ windows reflecting the rain which was now coming down in earnest. I stood at the side of the Cliffe House with a two storey arched window opening onto a cobbled courtyard bounded on three side by other large buildings, one looking as if it could have been a possible stables long ago.

This courtyard must have been where Walter housed his car after its sad encounter with a dog in the summer of 1929. ‘The defendant, Walter Edward Moss (41), dyer, Cliffe House, Hebden Bridge, was summoned by the police for driving his motor car in Todmorden Road, Burnley, on June 8th, at a speed dangerous to the public, having regard to all the circumstances. He pleaded not guilty. The defendant’s saloon car rounding the bend below Brooklands Road at a speed which he estimated at 35 to 40 miles hour. As the car was coming round the bend a mongrel dog was crossing at the same place as Greenwood, and the motorist ran straight into the dog, and carried it about ten yards before slowing up. Then the dog got free from the car, and went into Brooklands Road and died. The fact that the dog was killed was in itself no evidence of excessive speed. In these days there were so many accidents due to motorists swerving to avoid dogs, that a great number of them would not swerve for dogs, on account of the risk to the lives of passengers.’ Today two bright yellow sports cars were in occupation in the house’s forecourt. 15 ft above them a large iron bell hung, swaying silently in the driving rain. A semicircular drive fronted the house from which there was an uninterrupted view of the terraced top and bottom houses in the valley built for the mill workers. Walter would have been able to see Nutclough House, the detached home of his uncle, Mortimer Moss, another family member who made his fortune as a fustian manufacturer. By 1933 Phyllis, Walter and their two young sons had moved to a house with perhaps even more curb appeal than Cliffe House, and certainly with much more history for they have moved three miles East to Brearley Hall.

This beautiful stone mansion set in spacious grounds above the little village of Brearley is believed to date from 1621, encasing a much earlier timber framed structure which can still be seen in the rare timberwork in the open hall’s sling-brace roof, which according to the Halifax Antiquarian Society goes as far back as the 14th Century. In 1913 Arthur Comfort described this building in his book The Ancient’ Halls of Halifax: ‘Few homesteads are more pleasantly situated than Brearley Hall, which stands on an eminence between Mytholmroyd and Luddenden Foot. Dr John Fawcett, Baptist Minister, lived here for 20 years, and ran his private academy from here training future Ministers.’ Branwell Bronte, brother to his more famous sisters, lodged here when he was ‘clerk –in-charge’ at Luddendenfoot railway station. * branell statueWhen it was advertised for sale in 1928 the house was described as a ‘Fine old Residence with entrance hall, reception hall, dining, drawing, breakfast and billiard rooms, 8 bedrooms, w.c., bath, cottage, etc., with or without farm, about 18 acres.’ And now Walter, Phyllis and their son Edward, now a wholesale clothing manufacturer in his own right, are living in this mansion along with two other wellto-do families, one headed by a solicitor and the other by a civil and structural engineer.

I obtained the following recollections of living in the house from Walter’s son Geoffrey; “As for Brearley Hall we must have moved there in 1932 or 1933. We occupied the central and larger part. Our part had the main entrance, the back staircase, four bedrooms of which one was generally used by the maid, the drawing room, the dining room, kitchen, cellar, scullery, larder.” It was in this place of seeming peace and tranquility that Walter died on the 19th of July 1940, aged just 52, when he fell out of his toilet window. It is believed that he was leaning out in order to clear a blockage in the waste pipe from the bath or sink. The bathroom window did not open so Walter was leaning out of the toilet window and was using a stick to prod the waste pipe. According to the newspaper account while his wife was making breakfast Walter was in the bathroom shaving.She called out to him and on receiving no reply she looked out of the window and saw her husband lying on the path, unconscious. A doctor was summoned from Hebden Bridge which must have taken a considerable time and after receiving medical attention he was taken to hospital in Halifax where he died. He had suffered a fractured skull in his fall. Walter’s son Geoffrey shared with me his personal recollections. “This month July 2020 being the 80th anniversary of my father’s death on Friday July 19th, when I was only 9 years old, I have tried to recollect the happenings at that time. I was still at school in Birkdale Southport, Bickerton House School. I should have been collected by my parents and taken home on the 26th. I was informed by the headmaster that they could not fetch me. No reason given. As the headmaster had a caliper on one leg he did not drive and it was arranged that he would hire a taxi and take me to Huddersfield where we would be met. I have a vague recollection of being met by Mother and Peter who was home on compassionate leave from the RAF. I now assume that while we were travelling to Huddersfield the funeral was taking place at Rochdale crematorium. From what I can make out between Friday the 19th and Friday the 26th a considerable amount must have been hastily arranged: post mortem, inquest on the 22nd, and cremation.”

In January 2022 I found Walter’s grave in the cemetery at Wainsgate church near Pecket Well, along with his father, Abraham, and wife Phyllis.

Brearley Hall along with its 44 acres of formal gardens and woodland and paddocks. was purchased in 2019 as a children’s home providing specialist care and education for disadvantaged children. Phylis survived Walter by twenty seven years, spending her final years at Westfield Cottage in Mytholmroyd.

Recent Comments